"Canova's George Washington" It is unusual to base an exhibition around a work of art that no longer exists. However, in “Canova's George Washington,” the Frick Collection presents the absorbing story of a statue that was destroyed in 1831.

The story begins in 1816, when the General Assembly of North Carolina decided to commission a statue of George Washington for the State House in Raleigh. At the suggestion of Thomas Jefferson, North Carolina turned to the sculptor Antonio Canova. Canova was born in 1757 in the city of Possango, then part of the Venetian Republic. After the death of his father, Canova lived with his grandfather who was a stone mason and who owned a quarry. His grandfather encouraged the boy's interest in sculpture. By 1770, Canova was in Venice where he served and apprenticeship and went on to study at the Accademia di Belle Art di Venezia. After achieveing some success in Venice, Canova moved to Rome in 1780. There, he studied the works of Michelangelo as well as ancient Roman and Greek sculptures. His own works were purchased by the Pope and by other wealthy patrons. By 1800, he was one of the most famous artists in Europe. Europe was in tumult during this period. The French Revolution was followed by the Napoleonic Wars and for much of this period Italy was dominated by France. Canova produced works for various European leaders including several works for Napoleon and the Bonaparte family. Following,the fall of Napoleon, the Pope commissioned Canova to attempt to recover the Roman and Greek statues that Napoleon had taken from the Vatican. This diplomatic mission took Canova to England and France, increasing Canova's fame. While not completely successful, Canova did recover many of the statues. The Pope heaped honors upon Canova, among other things, inscribing his name into the Golden Book of Roman Nobles. Thus, Canova was at the height of his fame when he began work on the statue of Washington. Reportedly, Canova had an assistant read aloud a history of the American Revolution as Canova worked on the statue. He completed the project in 1821. It was the shipped to North Carolina and installed in the rotunda of the State House with great ceremony and to much acclaim. Tragically, a fire broke out in the State House in 1831. It engulfed the statue and the ceiling of the rotunda fell down upon it. The fragments of the statue were collected in hopes of restoring it but that task was never accomplished. Canova did not simply take a block of marble and start chipping away in order to make the statue. He began by doing drawings and then he made models, first in clay and then in stone. Finally, before starting on the full scale marble statue, Canova made a full scale plaster model. It is that model that is the centerpiece of the Frick exhibition. Canova sought to depict Washington writing his farewell address to the nation at the end of his presidency. The idea of a former military leader willingly and peacefully surrendering power was unprecedented and inspiring. It is an impressive statue. A somewhat larger than life figure is presented sitting gazing at a tablet. He is shown in thought, pausing for a moment, pen in hand. Canova had the ability to make his figures come alive and was able to avoid the coldness that so often afflicts monumental statues. This is not to say that there are no issues. First, there is the question of whether it is a good likeness of Washington. When Canova started work on the project, Washington had been dead for 16 years. Canova had never met him and there were no photographs. All that was available were some portraits and two statues that had been made from life. One was by Jean-Antone Houdon and one was by Giuseppe Ceracchi. While working on his statue, Houdon did a life mask of Washington. This is included in the exhibition as is Houdon's bust of Washington. These look like the familiar image we see in the portraits including the famous one by Gilbert Stuart, an autograph copy of which is also in the exhibition. The Cerrachi bust presents a different less familiar face. Canova worked from Ceracchi's bust. Jefferson, who served as Washington's Secretary of State, thought it was a good likeness but it is not the one that has come down through the centuries. Another issue is the way Washington is dressed. In those days, it was fashionable to present contemporary figures in ancient Greek or Roman attire. For example, in one of Canova's masterpieces, Pauline Bonaparte, who reportedly conquered as many men in her bedroom as her brother did on the battlefield, is presented as the Roman goddess Venus. Jefferson urged that Washington be attired in ancient costume here Canova agreed and presented Washington in the armor of a Roman general. This was a reference to the Roman hero Cincinnatus who led an army to repel an invasion and then returned to his farm once the war was won. Even in the early 19th century, some recognized the pretentiousness of dressing contemporary figures in antique garb. Indeed, Napoleon, who was not known for his modesty, rejected one of Canova's statues because it depicted him as a Roman god rather than in his French general's uniform. Washington repeatedly rejected all trappings of kingship. Placing him on a pedestal in Roman armor is simply not what Washington was about. Another issue is the gesture presented in the statue. As above, Washington is seen pen in hand pausing while he writes. However, the way he is dangling the pen makes him look like a dainty fop rather than a thinker, statesman and military leader. Still, even with these issues, the statue is an impressive work of art. The figure has energy, its features are beautifully crafted and as above, it avoids the lifelessness that you so often encounter in statues of famous figures. Furthermore, while the full scale model dominates, there is more to this exhibition. It traces how Canova created the piece. In his drawings and the preparatory models, you see how his ideas developed. The busts and the life mask, let you also see how an artist dealt with the problem of making a portrait of someone he never saw in the days before photography. As an added bonus, the exhibition includes a portrait of Canova by Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was probably the greatest English portrait painter of that period. |

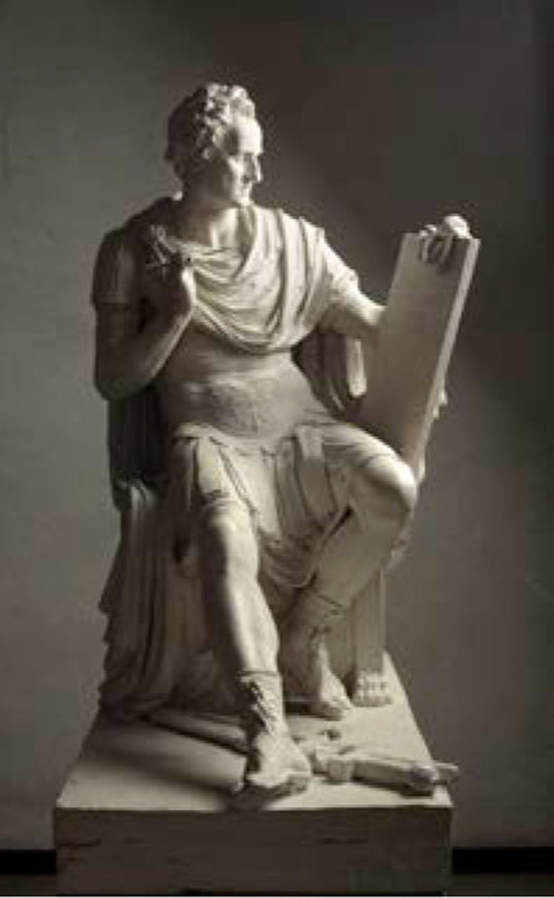

Canova's final model for the statue of George Washington (courtesy of the Frick Collection).

Above: The George Washington statue was created with the expectation that it would be placed in a rotunda. The exhibition displays the model in the Frick's Round Room, thus presenting it in a setting similar to the one Canova had in mind when he conceived the statue.

|

Art review - Frick Collection - "Canova's George Washington"