"Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera" “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera” at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art presents 50 abstract works by varous artists, some major names and some who are not so well-known.

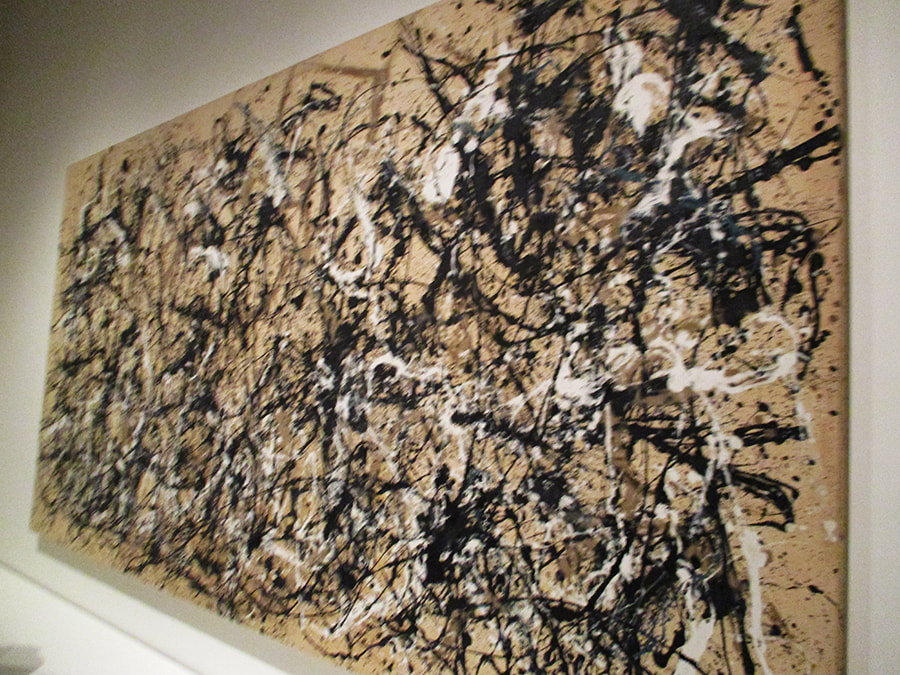

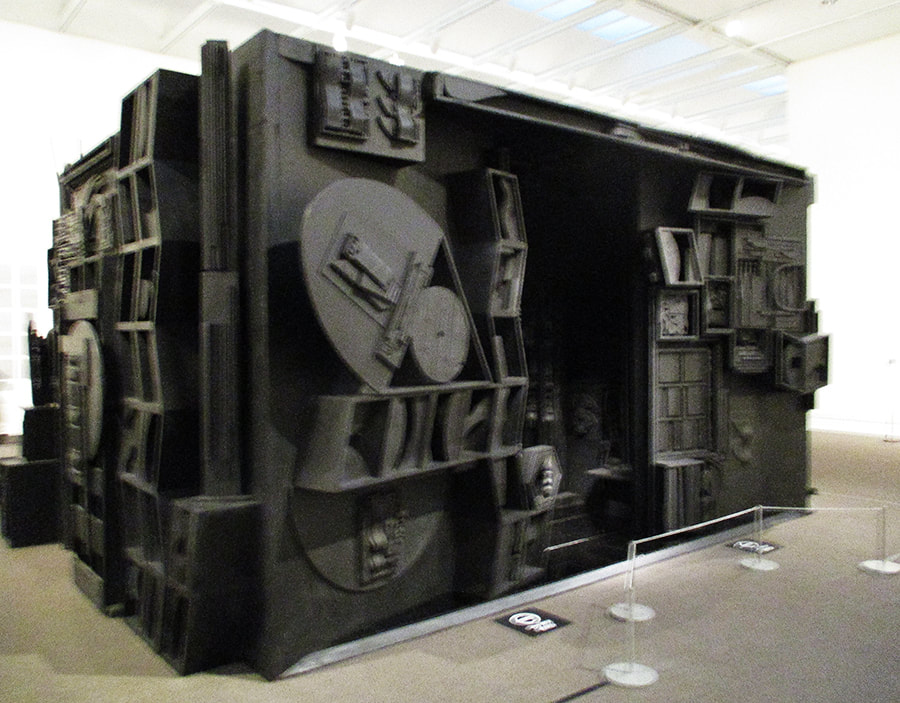

The common element of these works is that they are very big. According to the Met: “In the wake of unprecedented destruction and loss of life during World War II, many painters and sculptors working in the 1940s grew to believe that traditional easel painting and figurative sculpture no longer adequately conveyed the human condition. In this context, numerous artists, including Barnett Newman, Pollock, and others associated with the so-called New York School, were convinced that abstract styles—often on a large scale—most meaningfully evoked contemporary states of being. Many of the artists represented in Epic Abstraction worked in large formats not only to explore aesthetic elements of line, color, shape, and texture, but also to activate scale's metaphoric potential to evoke expansive—"epic"—ideas and subjects, including time, history, nature, the body, and existential concerns of the self.” The exhibition then presents examples of large paintings, sculptures and assemblages created from the post-war period through to the present day. While there is an emphasis on abstract expressionism, there are also examples of geometric abstraction and various other forms of abstract art. All of the works are complete abstraction. They do not portray people or landscapes. They do not tell a story. Thus, these are not abstract in the same sense that Matisse's “Dancers” or Picasso's “Guernica” are abstract works. Like instrumental music, the works in this exhibition convey their message by evoking emotions and thought. By definition, there are no pictures or reality or words to guide the viewer. In these works, size plays a role in conveying the message. For example, Louise Nevelson's “Mrs. N's Palace” conveys feels of oppression and coldness like the nightmarish images of future cities in some science fiction films. It does this in part because it is a huge object taking up most of one of the galleries. If she had created the same object say in the size of an architectural model, it would not have been so powerful. Similarly, Jackson Pollock's drip painting “Autumn Rythym (Number 30)” obtains power from its size. Filled with chaotic energy, it is too large to be ignored. Pollock's “Number 28,”while still a large work, is smaller and has a more intimate feel. It speaks more quietly. Along the same lines, Carmen Herrera's “Equilibrio,” a geometric abstraction, would not work as well if it had been done in a smaller scale. In applying the same test to the rest of the works in the exhibition, I found that their size did help them speak. Indeed, size was often part of the message. However, there has to be a reason for creating a work in a large size. Two of the most interesting works in the exhibition are abstract watercolors by Mark Rothko, which, while big, are dwarfed by the monumental size of his color field works on display in the same gallery. Something that the exhibition does not deal with is the big for bigness sake phenomenon that has plagued the art world over the last half century. By the 1960s, bigness had become fashionable in the art establishment. Since the leading artists of the day were working in epic size; the art establishment adopted the view that only big works were good art. Everything else was passe. In addition, in the era following the Second World War, corporations built numerous new corporate headquarters and office buildings in the International style. To go with these “modern buildings,” the corporations looked for equally modern art work. (Corporations like to feel that they are in tune with the times). Often this meant buying abstract works. Furthermore, works done on an epic scale could fill the large lobbies and cavernous spaces of these buildings. Since there was a demand, some artists turned to large size works. This phenomenon has produced some mediocre art. Just as not everything that is shouted is worth hearing, not everything that is big is worthwhile art. You do not always have to shout to get your message across. It would have been difficult for the Met to have addressed this phenomenon in this exhibition. As above, the works presented here are large for valid reasons. However, inasmuch as the success of epic works by the likes of Pollock and Rothko indirectly helped trigger the bigness for bigness sake phenomenon, some mention might have been in order. |

Above: The size of Jackson's Pollock's "Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) says "I am here, look at my emotional frenzy."

Above: The epic size of Louise Neleson's "Mrs. N's Palace" adds to the sense of foreboding conveyed by the work.

|

Art review - Metropolitan Museum of Art - “Epic Abstraction”