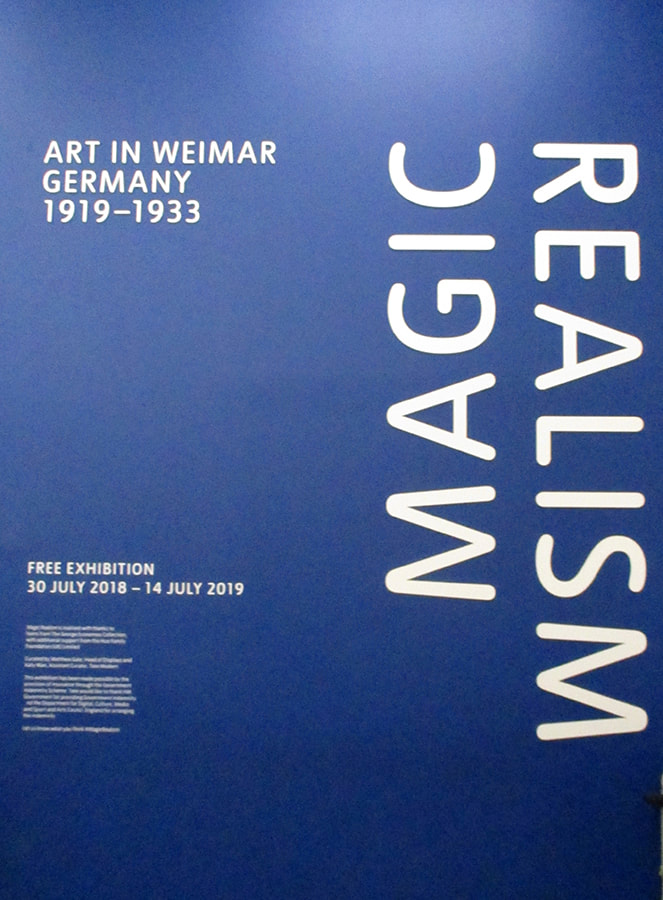

"Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany" “Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany” at the Tate Modern in London presents a selection of works from Germany the years in the years between the World Wars. It includes works of several artists from the Tate's own collection as well as works loaned from The George Economou Collection.

1,773,700 German soldiers died in World War I and another 4,216,058 were wounded. 1,152,800 were taken prisoner, for a total of 7,142,558 casualties, - - 54.6 percent of the 13,000,000 the German soldiers who participated in the war. This all took place under horrid conditions. And for the Germans, all of this was in a losing cause. Not only did post-war German society have to deal with the physical and psychological scars of the war but it had to adapt to a vastly changed world. The Kaiser and the old system of government were gone. Extremist political groups on the right and on the left were attempting coups seeking to bring down the shaky democratic government of the new Weimar Republic. Reparations imposed by the Versailles Peace Treaty were placing a heavy burden on the economy as was run away hyper-inflation. Eventually, in the 1920s, the situation began to stabilize. Loans from America brought prosperity. An attitude of permissiveness emerged which sometimes bordered on depravity in places like Berlin. Then when the Great Depression struck, the economy again collapsed. This provided fertile ground for the hate groups. By 1933, the Weimar period was over, replaced by the Nazi nightmare. The art of this period played two roles. First, it reflected the self-analysis of the artists who were impacted by the war and by the subsequent societal changes. Second, it presented the artists' observation and commentary on the times. In this exhibition, we see that many artists turned away from the abstraction of the period before World War I and turned to realism. The German art historian Franz Roh called this new realism “Magic Realism.” He saw that it contained two approaches. First, there were the “classical artists” who were inclined toward chronicling everyday life through precise observation. Second, there were the “vertists” who took a more satirical approach to commenting on life and society. Sometimes both approaches can be seen in the same picture. For example, Otto Dix's “Portrait of Bruno Alexander Roscher” looks like a traditional realistic portrait of a military figure. However, the subject's foolish expression reveals an element of satire and criticism. A favorite subject of these artists was the circus. The circus provided subjects that had beauty, fear and desire. It was a fantasy land. At the same time, it was home to outcasts and misfits. The potential for satire and social commentary was abundant. Not all the social commentary was so metaphorical. For example, Jeanne Mammen's drawings of women with modern hairstyles and smoking commented on the fact that the role of women was now quite different than it was before World War I. Overhanging these works is a sense of tragedy. We know that a nightmare much more catastrophic than anything hinted at by the artists swept away the world that they were observing. |

Above: Otto Dix, “Portrait of Bruno Alexander Roscher”.

Below: Jeanne Mamen, “Boring Dolls.” |

Art review - Tate Modern - “Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany"