ART REVIEW: “John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal”

“John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal” at the Morgan Library and Museum presents some 50 works by America's leading portrait artist. Assembled by the Morgan in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery (U.S.), the works are from a wide assortment of public and private collections.

Sargent was born in 1856 in Florence, Italy into an ex-patrirate American family. His formal art education was in Paris where he studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and worked in the atelier of Carolus Duran, a fashionable portrait painter. Despite his connection to the official French art school, Sargent was influenced by the modernist rebels working in Paris such as Edouard Manet. Along the same lines, he became close friends with Claude Monet. At first, Sargent found success in Paris. However, his stylized portrait “Madame X” was considered shocking when it was shown in 1884. The scandal led Sargent to abandon Paris and move to London. However, his career as a portrait painter was not revived until he made a visit to the United States in 1887. After that, the rich and famous both in the United States and in Britain flooded him with portrait commissions. By 1907, however, Sargent had had enough of oil portraits and announced that he would henceforth only do portrait drawings in charcoal. (He continued, however, painting landscapes and murals both in oils and in watercolor). With only a few exceptions Sargent kept to his vow. However, this did not discourage people from commissioning portraits. In all, Sargent Sargent made some 750 portrait drawings, the majority of which were created after 1907. Why Sargent abandoned oil portraits is something of a mystery. They had brought him international fame and both at the time and now they were/are recognized for their artistic brilliance. Of course, history is full of examples of artists, musicians and actors who came to feel that the thing that had brought them success had become too confining. Perhaps Sargent felt trapped by the routine of painting portrait commissions. In any event, it is known that Sargent wanted more time for his murals and landscapes. Charcoal drawings could be executed quickly. Most were done in three hour sittings whereas an oil portrait involved numerous sittings as well as time spent in the studio finishing the painting. In addition, Sargent was quite adept at charcoal drawings. His studies at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts had focused on draftsmanship. This is not to say, however, that his charcoal portraits were academic drawings. He developed his own style that combined tradition and modernism. It was looser and more energetic than the drawings of the academy. The drawings also were a means of expression for Sargent. This is supported by the fact that not all of the charcoal portraits were done as commissions. For example, Sargent wrote to actress Ethel Barrymore requesting that she sit for a portrait (left). One thing that is puzzling about Sargent's shift to charcoal is that it involved forsaking color for black and white. As above, Sargent was friends with Monet and was very interested in Impressionism, which is all about color. Perhaps Sargent felt that his landscapes provided sufficient means to pursue his interest in color. Perhaps he was interested in translating light and color into black and white images. As the exhibition at the Morgan documents, the people who sat for Sargent's drawings were the celebrities of the day. Included are portraits of writers, poets, actors, artists, musicians, world leaders, soldiers, titled aristocrats, socialites and rich industrialists. Some like Winston Churchill, W.B. Yeats, and Henry James remain famous today. Others were only famous in their era. In either case, it is interesting to see how Sargent handled creating a portrait of them. But, these drawings would be interesting even if the identities of the sitters were unknown. Sargent was able to capture and transmit the essence of his sitters. Sargent did not just capture a physical likeness but something of these people's vitality. As a result, the drawings transcend the identity of the sitters and say something about people in general. For those who are interested in creating art, Sargent's drawings present a master class in portraiture. Sargent was not a photo-realist or a copying machine. He made decisions about which lines and shadows were essential to the message he wanted to present about his subject. His economy in making marks on the paper is instructive as are his decisions as to contrast, background and clothing. Accompanying the exhibition is an excellent catalogue written by Richard Ormond. Not only does it contain high quality images of the works but it includes information about Sargent's life, his methods and his materials as well as information about the sitters depicted in each work. Moreover, it is quite readable. This exhibition presents a rare opportunity as this many of Sargent's charcoal drawings have seldom been presented together before. When the drawings were produced, they went immediately into private collections without being exhibited. While quite a few now are in public collections, they are widely dispersed. Furthermore, inasmuch as these are works on paper and subject to deterioration from light, they cannot be exhibited constantly. Therefore, it is unlikely that such a superb gathering of Sargent drawings will be repeated soon. |

Above: Sargent's portrait of Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (later the Queen Mother).

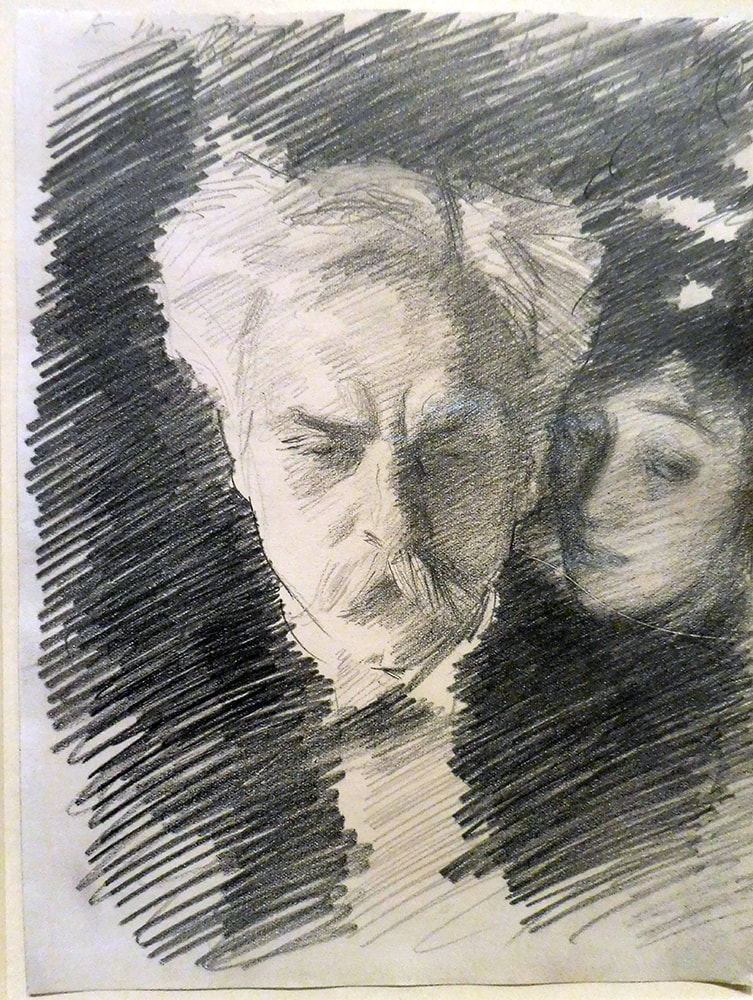

Above: Gabriel Faure and Mrs. Patrick Campbell.

Below: Lady Helen Venetia Vincent. Above: Charlotte Nichols Greene and her son Stephen Greene.

|

Art review - Morgan Library and Museum - John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal