AN APPRECIATION: Edgar Degas Edgar Degas Self-portrait Edgar Degas Self-portrait

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born in July 1834 in Paris, France. His father was a native Frenchman but his mother was a Creole from New Orleans. It was a prosperous family that included a number of titled aristocrats.

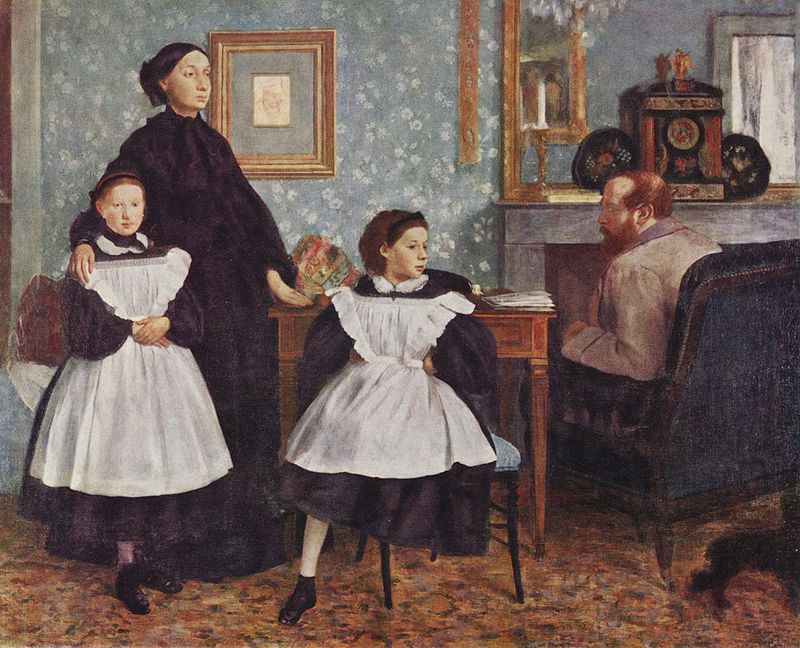

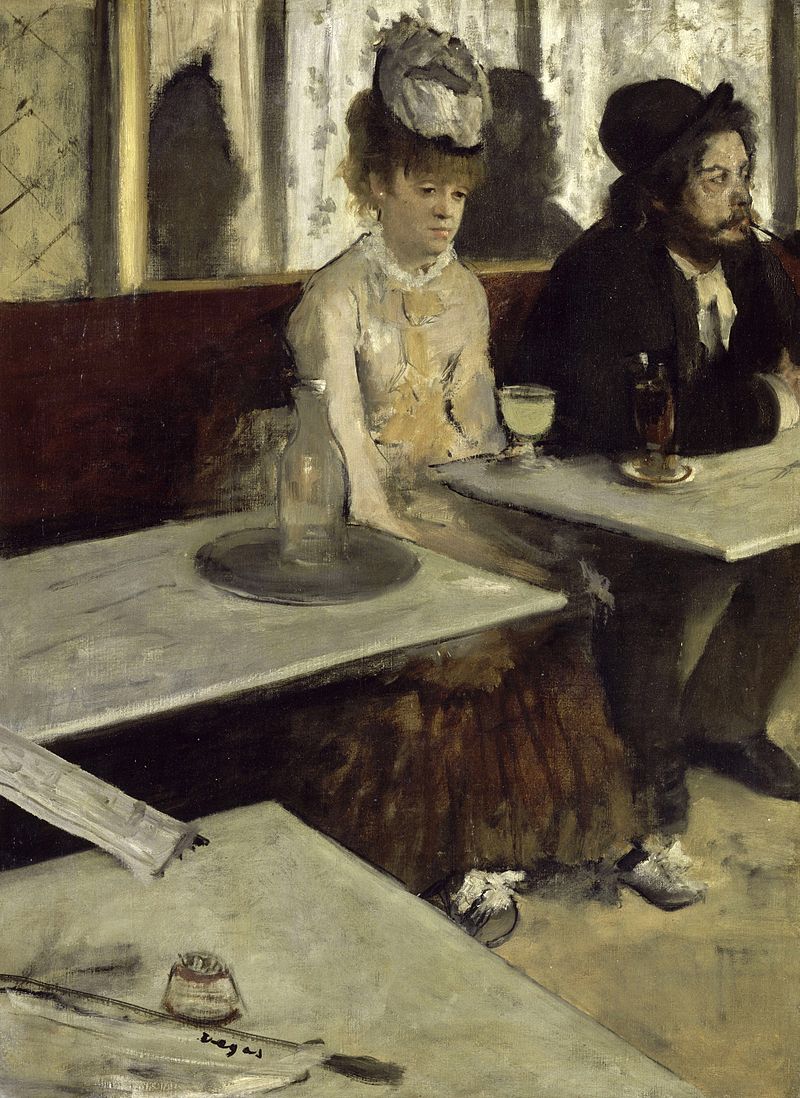

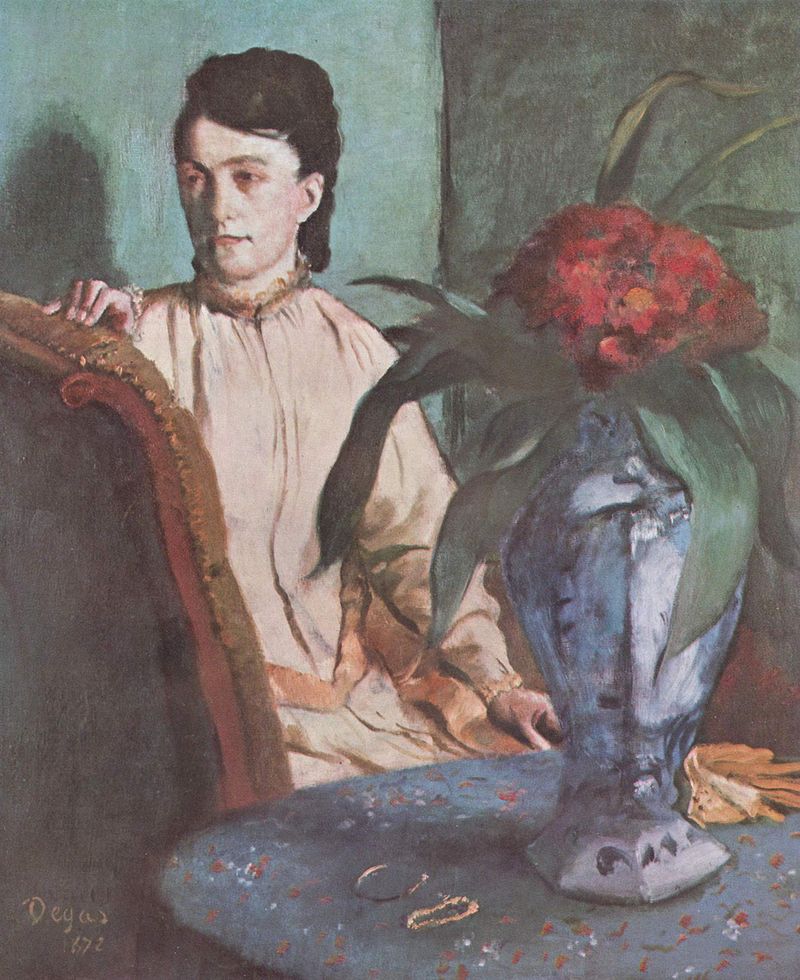

Edgar's mother died when he was 13 and so his upbringing was left to his father. A banker by profession, Pierre-Auguste de Gas was also interested in the arts. He would organize musical recitals that were held in the family home and he would often take his son to art museums. When Edgar turned 18, a room in the family home was converted into an art studio for Edgar. Despite his father's interest in the arts, his desire was for his son to have “a profession” and perhaps assist with the family business. Therefore, Edgar was educated at the prestigious Lycee Louis-Grande and then enrolled in the law school of the University of Paris. Edgar took little interest in his legal studies. He spent much of his time at the Louvre copying the work of the great masters. Consequently, with his father's consent, he enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the art school of the prestigious Academie des Beaux Arts (the “Academy”). There, he studied with Louis Lamonte, a disciple of Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres. Ingres was the most revered contemporary artist of the time and he became a hero to Degas. Advocating the importance of line, Ingres was firmly rooted in classical tradition. Through his father, Degas was introduced to Ingres who advised him: "Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist." Degas often repeated this anecdote throughout his life demonstrating its impact on him. At the same time, Degas was intrigued by art of Eugene Delacroix, who was Ingres' rival. Delacroix's art emphasized the importance of color rather than line. Throughout his career, Degas sought to reconcile these two approaches to art. By 1856, Degas had decided that the Ecole des Beaux Arts' traditional approach to teaching art was unproductive. Therefore, he took the money his father had given him to study there and used it to go to Italy. This was not a holiday jaunt but rather an artistic journey. He made copies of the art of Michelangelo, Raphael and other classical artists. However, he also studied the more color-oriented Venetian artists. When he returned to Paris, he set up a studio where he painted portraits and scenes from history. Under the accepted-academic principles of the day, these two subjects were considered the highest forms of visual art. Degas also submitted works to the Paris Salon, the annual art exhibition held by the Academy. His submissions were accepted for exhibition but most attracted little attention. During this period (the early 1860s), Degas met Edouard Manet while copying a painting at the Louvre. Manet had become notorious, not only for his non-traditional artistic style but for his depictions of modern life rather than scenes taken from history or classical myths. Finding that they had similar backgrounds and much in common, the two artists became friends. Through Manet, Degas met a number of young artists who spent time at the Cafe Guerbois including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. Like Manet, these artists were interested in depicting modern life. They were also dissatisfied with the conventional approach of the Academy. Degas joined in their debates. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 intruded upon these debates. Degas enlisted in the National Guard and served in an artillery regiment. It was during this time that he noticed that he was having problems with his eyes. After the war, Degas traveled to New Orleans to visit his mother's family. At first, he was intrigued by the novelty of the experience and produced a number of paintings but he found that the bright light bothered his eyes and so he returned to Paris in 1873. Degas' father died in 1874. However, Degas discovered that his brother had amassed a large amount of debt. To preserve the family reputation, Degas used his inheritance and sold his house in order to pay his brother's debts. Even before the war, Degas' friends from the Cafe Guerbois had been talking about holding their own exhibition as an alternative to the Paris Salon. Degas, now dependent on selling his art for a living, became a leading proponent of this idea. As a result, 15 young artists banded together to hold an exhibition at a photographer's studio in Paris. The critics attacked the exhibition, derisively calling the group “Impressionists” - - a name taken from one of Monet's landscapes. Degas hated this label, preferring to be called a “Realist.” However, he sold a number of his paintings as a result of the exhibition. Over the next 12 years, Degas participated in all but one of the succeeding Impressionist exhibitions. Moreover, he became a leading organizer, bringing in new artists as members of the original group dropped out. After the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886, Degas stopped submitting works to public exhibitions, preferring to sell his art through the Durant-Ruel gallery. Degas had become a financially successful artist. His paintings of dancers, horse racing and backstage at the theater sold well. Some of his slice of modern life pictures still shocked the public but that only served to increase his fame. At the same time, Degas' style was evolving. His art was rooted in the classical approach and was an excellent draughtsman but he was also a master of achieving light effects with color. Ideas inspired by Japanese prints and photography were incorporated into Degas' art. Degas also experimented with other media. He made wax statues of dancers and of horses. (These were not cast in bronze until after Degas' death). Lithography and photography also triggered his interest. The medium with which he has became most closely identified with is pastels. In part, he turned to this medium because of his deteriorating eyesight. However, it also attracted him because it enabled him to combine drawing and color, thus reconciling his interests in line and in the use of color. As time went on, his pastels became increasing abstract thus laying a foundation for the new art of the next century. By the beginning of the new century, Degas' artistic output had become a trickle. His eyesight was nearly gone and he withdrew into himself. In 1912, when his longtime residence and studio were slated for demolition and he had to move, he appears to have given up art altogether. He died in 1917. Private life Degas believed that an “artist must live alone and his private life must remain unknown.” True to this philosophy, Degas lived a solitary existence, often pushing away others. For example, Degas had many friends including Manet and the other artists who gathered at the Cafe Guerbois. However, he is said to have held himself apart at these gatherings breaking in to advocate a point forcefully, unleash his caustic wit or to express an unpopular opinion such as antisemitism. Renoir reportedly said: "What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn't stay till the end." Yet, people were his favorite subjects. Along the same lines, Degas never married. Instead, he cultivated a reputation as a misanthropic bachelor. However, he was a close friend of a number of women including Mary Cassatt who he helped with her art. Perhaps more importantly, the vast majority of his works were depictions of women. These are not just depictions of the female form but include pictures such as “L'Abinthe,” “The Bellelli Family” “Mademoiselle Dihau at the Piano”and “The Lady with the Flower Vase” that look inside the women depicted and display understanding. Like a number of other artists such as Gauguin and Caravaggio, Degas does not come across as an attractive person. From the vantage point of more than a century later, however, one has to wonder how much of the persona he cultivated was a defense mechanism to prevent people from getting too close rather than genuine manifestations of his personality. Analysis Degas' art is different than what we usually think of Impressionist art. Whereas the most frequent subject depicted in Impressionist art is the landscape, Degas did very few landscapes, he focused almost entirely on people. Whereas the other Impressionists believed strongly in spontaneous plein air painting, Degas worked in his studio and carefully composed and prepared his paintings. Nonetheless, Degas is an Impressionist for at least four reasons. First, he was part of the original Impressionist exhibition. Indeed, he was a driving force behind the group coming together and continued to be a force in the movement throughout its existence. Second, like the other Impressionists, he believed in depicting modern life rather than the traditional subjects endorsed by the academy. Third, like the other Impressionists, he was a master of color and reproducing light effects. The others typically displayed this skill with outdoor subjects. Degas did it with regard to indoor lighting such as stage lights. Fourth, Degas painted impressions - - albeit somewhat differently than his colleagues. The others painted impressions based upon what was taking place before their eyes. Degas worked primarily from memory. “It is all very well to copy what you see but it is much better to see what you still see in your memory. This is a transformation in which imagination collaborates with memory. Then you only reproduce what has struck you, that is to say the essential, and so your memories and your fantasy are freed from the tyranny which nature holds over them.” See our profiles of these other Impressionists and members of their circle.

Frederic Bazille Eugene Boudin Marie Bracquemond Gustave Caillebotte Mary Cassatt Paul Cezanne Henri Fantin-Latour Paul Gauguin Eva Gonzales Armand Guillaumin Edouard Manet Claude Monet (Part I The Early Years) Claude Monet (Part II High Impressionism) Claude Monet (Part III The Giverny Years) Berthe Morisot Camille Pissarro Pierre Auguste Renoir Alfred Sisley Suzanne Valadon Victor Vignon |

Above: "The Dance Class". More than half of Degas' works feature dancers.

Below: An early masterpiece "The Bellelli Family" Degas often returned to the same subject. Above: "In the Cafe" also known as “L'Abinthe."

Below: Another picture entitled "In the Cafe". Above: Degas depicts the effects of stage lighting in this theater picture.

Below: In the 1880s, Degas turned to scenes of women bathing and other private moments as subjects. Above: "Lady with a Flower Vase".

|

Artist appreciation -Edgar Degas