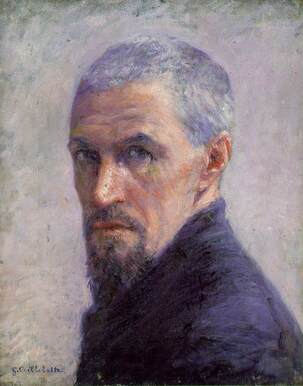

AN APPRECIATION: Gustave Caillebotte Self-portrait Self-portrait

Gustave Caillebotte is not the best known of the Impressionists. However, he was a crucial member of that circle. Independently wealthy, he used his fortune to provide support to the Impressionists and to promote their art. At the same time, he was creating original art that extended the breadth to the Impressionist movement.

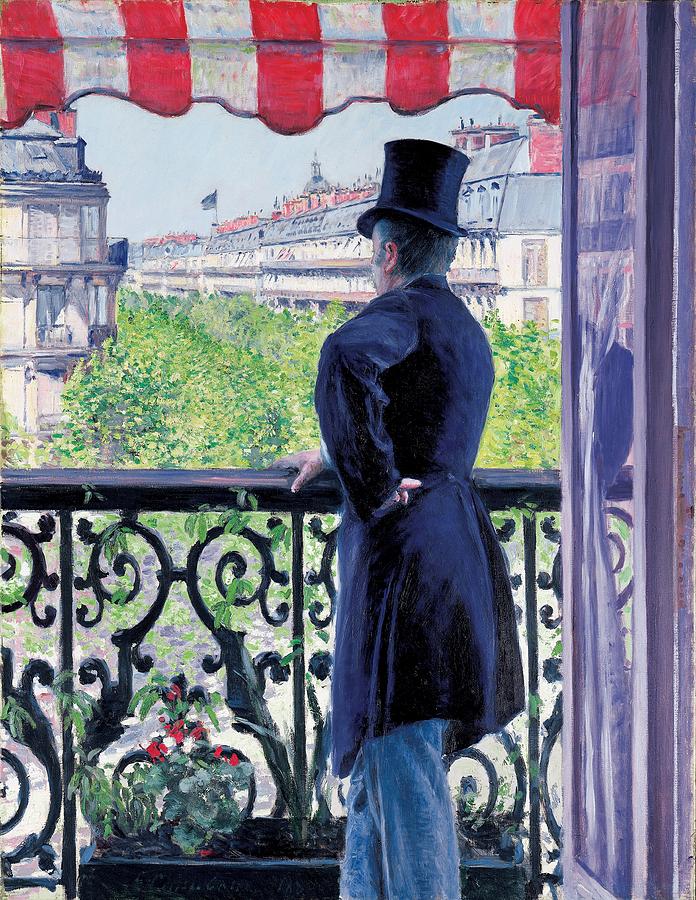

Career Caillebotte was born in Paris in 1848. He was eldest of the three children of his father's third wife. It was a well-to-do family. Caillebotte's father had inherited a fortune made in the textile business and was a judge. The family lived in a good section of Paris but spent the summers at their country estate at Yerres south of the capital. Following in his father's footsteps, Gustave earned a law degree and obtained a license to practice law. He also studied engineering. Shortly after he finished his education, the Franco-Prussian War intervened. Caillebotte was drafted into the national guard and served from July 1870 to March 1871. After the war, Caillebotte decided to pursue a career in art. He began visiting the studio of Leon Bonnat, who encouraged Caillebotte's interest in art. Bonnat was a realist painter who taught classes at the Academie des Beaux Arts, the prestigious official French art school. Naturally, Caillebotte enrolled at the Academy. Caillebotte did not stay long at the Academy. Through Bonnat he met Edgar Degas, one of the young artists who rejected the Academy's traditional approach to art. As a result, Caillebotte met other young rebels including Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who became a good friend. They exposed Caillebotte to their new approach to art. He attended but did not participate in the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. However, he participated in the Second Exhibition and by the Third Impressionist Exhibition, he was one of the organizers and helped to finance the exhibitions. He went on to be a central figure in the exhibitions participating in all the remaining exhibitions except the Sixth (due to a dispute with Degas) and the Eighth. Caillebotte's father had died in 1874 and his mother in 1878. As a result, Caillebotte inherited a large fortune. This meant that unlike his colleagues, Caillebotte did not have to depend upon selling his art for his living. He was also able to spend money on things that would be useful in making art. For example, he had a carriage equipped as a mobile art studio. In addition, Caillebotte's fortune enabled him to provide financial support to his poverty stricken colleagues such as Monet. This help came in the form of paying their bills as well as through the purchase of their art at a time when no one else was buying their art. Consequently, Caillebotte assembled a large collection of Impressionist masterpieces. By the late 1880s, Caillebotte's interest in creating art was waning. He was pursuing other interests including building yachts, collecting stamps and gardening at the estate that he had purchased at Petit-Gennevilliers. It was while he was working in his garden that Caillebotte suffered a stroke and died in 1894. In his will, Caillebotte bequeathed a large number of the paintings that he had collected to the French state. These included some 67 works by Renoir, Cezanne, Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissaro and Sisley. Among theses works were numerous paintings that are now recognized as masterpieces. Realizing that the Impressionism was still viewed with scorn by the art establishment. Caillebotte took measures to protect this collection. First, he specified that the paintings would not come into the hands of the government until 20 years after his death. By then, he hoped that these paintings' real worth would be recognized by the establishment. Second, he specified that the works not be relegated to some “attic or provincial museum” but rather be displayed in the Louvre or the Luxembourg Museum, which was then reserved for works by living artists. As Caillebotte had foreseen, the bequest enraged the art establishment. Protests were sent to the government and a campaign was commenced by some members of the press urging the rejection of the Caillebotte collection. A committee of museum officials was put together in order to meet with Caillebotte's executors to look for a compromise. Among the executors were Renoir and Caillebotte's brother Martial. Eventually, a compromise was reached under which the French government accepted 38 works for the Luxembourg Museum. This did not satisfy the art establishment and a written protest was sent to the government by the Academy. Over the next 20 years, Martial Caillebotte attempted to get the government to accept the paintings that had been rejected in 1896 but without success. When the government finally realized its mistake and sought to claim the other works in 1928, Martial's widow refused. Nonetheless, the Caillebotte collection forms the core of the French national collection of Impressionist works. Private life Following the untimely death of his brother Rene in 1876, Caillebotte became convinced that he would die early. (This prediction came true as he died when he was 45). Therefore, Caillebotte threw himself into his various interests with passion. Consequently, he became recognized not only as an artist but as a textile designer, a stamp collector and a yachtsman. Caillebotte never married. However, there is speculation that he had a long-term relationship with Charlotte Berthier, who was 11 years younger than Caillebotte and from a lower social class. The speculation appears to be based upon the fact that he left her a large annuity in his will. Analysis Because Caillebotte was independently wealthy, he was free to pursue any style that interested him and he was free from any need to please critics or the public. Consequently, he did not work in any one particular style or focus exclusively on one theme. In some of his work, one can see the influence of Monet while in others there is the influence of Degas and Manet. He is best known for his urban scenes but he also did scenes of the country. Caillebotte's work is more firmly rooted in traditional drawing than the other Impressionists. However, like them, he was interested in depicting moments from everyday contemporary life rather than the traditional subjects endorsed by the Academy. For example, “The Floor Scrapers” was considered vulgar and rejected by the Salon of 1975 because it depicted modern urban workmen. Hallmarks of Caillebotte's work include the unusual use of perspective and unusual cropping of the image. An example of the former is “Paris Street, Rainy Day” and of the latter “L'homme au balcon, Boulevard Haussmann.” These may be the result of his interest in Japanese prints and photography. |

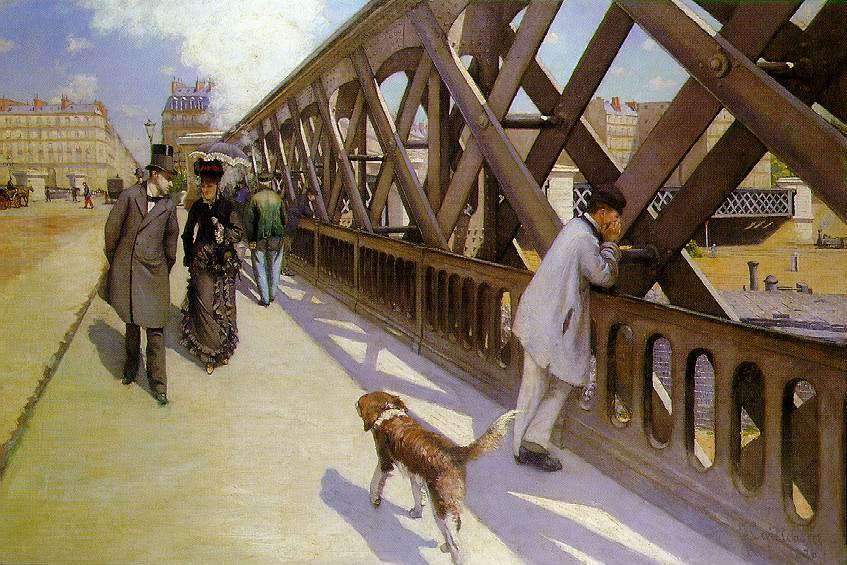

Two of Caillebotte's best known works "Paris Street, Rainy Day" (above) and "Le Pont de l'Europe" were of scenes only a short distance from his house in Paris.

In "Boulevard des Italianes" (above), Caillebotte depicted a scene in a similar manner as in works by Monet and Pissarro. However, in "Le Homme au balcon, Boulevard Haussmann" (below), Caillebotte addressed this theme in a manner uniquely his own.

Although best known for his depictions of urban life, Caillebotte also painted more rural landscapes such as this scene of his garden at Petit-Gennevilliers (above).

See our profiles of these other Impressionists and members of their circle.

Frederic Bazille Eugene Boudin Marie Bracquemond Mary Cassatt Paul Cezanne Edgar Degas Henri Fantin-Latour Paul Gauguin Eva Gonzales Armand Guillaumin Edouard Manet Claude Monet (Part I The Early Years) Claude Monet (Part II High Impressionism) Claude Monet (Part III The Giverny Years) Berthe Morisot Camille Pissarro Pierre Auguste Renoir Alfred Sisley Suzanne Valadon Victor Vignon |

Artist appreciation - Gustave Caillebotte