The Eight Impressionist Exhibitions In the space of little more than a decade beginning in 1874, a series of exhibitions were held in Paris, France that changed the course of art. For the most part, the exhibitions were not successful either commercially or critically. However, they did serve to bring the work of a group of unknown avant garde artists to public attention. Without them, Impressionism may have gone unnoticed.

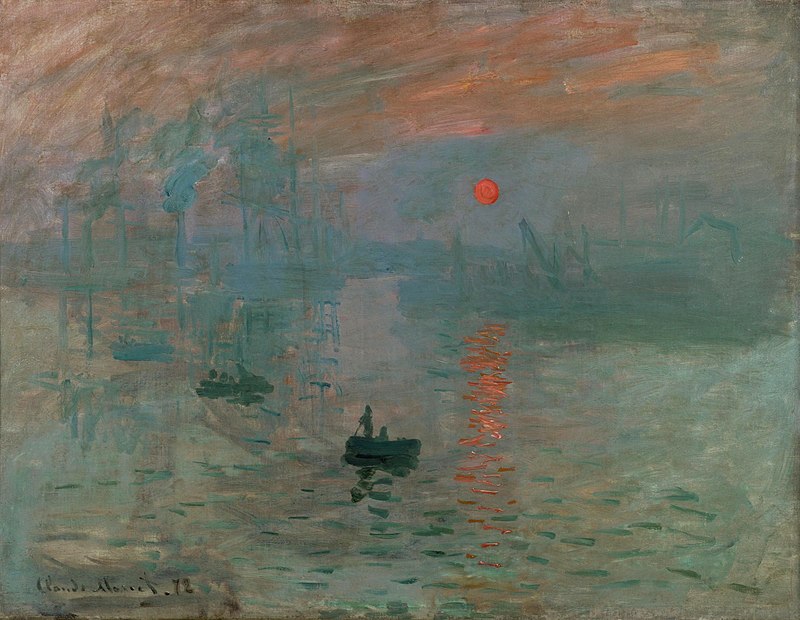

Origins and The First Exhibition The Impressionist Exhibitions began as an alternative to the official state sponsored art exhibition known as the Paris Salon. If an artist's work was shown at the Paris Salon, it could end up being purchased by the French government or a commission to decorate a government building might follow. In addition, showing work at the Salon was a stamp of approval. Collectors and the public knew that they were buying good art when they purchased a work by an artist who showed at the Paris Salon. Furthermore, at this time, it was difficult for an artists to make a name for himself or herself by any other means as there were few commercial galleries. Any artist could submit works for inclusion in the annual Salon. However, a jury decided which works would be exhibited and where they would be hung in the exhibition. The juries were dominated by academicians connected to the state-sponsored art school, the Academy des Beaux Arts. The Academy had very decided ideas about the proper subject for art and the techniques that should be used. Consequently, works that did not comply with the Academy's principles were usually rejected and not shown at the Paris Salon. Edouard Manet challenged the system by submitting works that did not comply with the Academy's principles either in subject or technique. For the 1863 Salon, he submitted “Déjeuner sur l'herbe,” a painting showing two modern men at a picnic with two partially-clad women painted in a way that the academicians considered unfinished. It was rejected. However, so many paintings were rejected that year that Emperor Napoleon III called for an exhibition of the rejected paintings. Manet's scandalous painting was the talk of the exhibition. For the 1865 Salon, Manet submitted “Olympia.” This painting of a nude woman was accepted but again caused a scandal. Manet's challenge made him a hero to a number of young artists who did not want to be confined to the Academy's subjects and techniques. Although the Salon occasionally accepted one of their works, most of these artists had felt the disappointment of having major works rejected by the Salon. They gathered around Manet socializing and debating questions of art at places like the Cafe Guerbois. During these debates, the idea surfaced of forming some type of mutually supportive organization. Camille Pissarro, who had socialist views, was a driving force behind this idea and eventually an organization was formed with a charter based upon the baker's guild in Pontoise, where Pissaro was living at the time. From time-to-time, Frederic Bazille's idea of holding a group exhibition was floated. This idea remained a dream until after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the Paris Commune that followed the war. As a backlash to the Commune, the Salon jury started rejecting anything that might be viewed as revolutionary. This included the work being done by Manet and his disciples. As a result, there was more urgency to finding an alternative to the Salon. Also, around this time, Edgar Degas undertook to repay a massive debt incurred by his brother. Consequently, the formerly independently wealthy Degas was now more dependent upon his art for his living. Therefore, he turned his energies toward making the dream of a group exhibition a reality. By 1874, most of the artists who socialized at the Cafe Guerbois had agreed to participate. This included the avant garde artists Degas, Pissaro, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cezanne, Armand Guillaumin and Berthe Morisot. Degas suggested that it might seem less aggressive, if they also invited some conformist artists to participate in the exhibition. What must have been a severe disappointment to the group, their hero Manet refused to participate. He explained that he viewed the Salon as the only proper battlefield for art. Furthermore, he confided to Monet that he did not want to exhibit with Cezanne, who was known for his difficult personality. (Indeed, Pissarro had to fight to have Cezanne included in the exhibition). Space for the exhibition was found in the studio of the photographer Nadar on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. Thirty artists participated showing 165 works. It ran from April 15 to May 15 1874. Some 4,000 people viewed the exhibition. Many came to laugh at these strange, unfinished paintings. The critics were also far from kind. One of the critics gave the group the name that history knows them by today. Officially, the group used the name of Pissarro's cooperative calling themselves “The Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc.” - - not a very catchy name. One of the critics, Louis Leroy, decided that it would be more descriptive to borrow the name of a painting he particularly disliked. Monet had not given much thought to the name of this painting. It had been untitled when it arrived for the exhibition and Renoir's brother Edmund who was in charge of compiling the catalogue had to keep pestering Monet for a name. Eventually, Monet said “call it Impression: Sunrise.” Incensed at the group's apparently casual approach to art, Leroy derisively dismissed the group as just a bunch of “Impressionists.” Leroy's name stuck. Most of the artists did not like it at first (Degas never accepted it) but over time, they came round to it. Indeed, by the Third Exhibition, it was the group's official name. Another target of the critics was Manet. Although he did not participate in the exhibition, the critics recognized that the exhibition's core group of artists were Manet's followers. Accordingly, they assumed that Manet was the ring leader. Besides, he was better known than the artists who did participate and thus attacks on him were more likely to interest readers. The exhibition was not a financial success either. It incurred a large loss which the members of Pissarro's cooperative had to bear and the company was disbanded. The Second Exhibition Despite the failure of the First Exhibition, Monet and Renoir persuaded the core group to try again in April 1876. This time the exhibition was held at the Durant-Ruel Gallery. Art dealer Paul Durant-Ruel had become interested in Manet and his circle. He would go on to play a major role in making the Impressionists popular. A newcomer to the group was also to play an important role in promoting Impressionism. Gustave Caillebotte used both his fortune and his organizational skills in putting together the exhibition. However, Degas was reportedly offended as Caillebotte assumed some of the duties Degas had previously exercised as the unofficial manager of the exhibitions. In addition to Caillebotte, 19 artists participated showing 252 works. Most of the major Impressionists participated including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas, Sisley and Morisot. Cezanne, who was irritated with Monet, did not. Attendance at the exhibition was less than at the First Exhibition. However, it was sufficient for the group to recoup its expenses and for each artist to receive three francs as profit. Most of the critics were still hostile but some good reviews provided a source of hope. In addition, a number of the exhibited works were sold. CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE See our profiles of these Impressionists and members of their circle.

Frederic Bazille Eugene Boudin Marie Bracquemond Gustave Caillebotte Mary Cassatt Paul Cezanne Edgar Degas Henri Fantin-Latour Eva Gonzales Paul Gauguin Armand Guillaumin Edouard Manet Claude Monet (Part I The Early Years) Claude Monet (Part II High Impressionism) Claude Monet (Part III The Giverny Years) Berthe Morisot Camille Pissarro Pierre Auguste Renoir Alfred Sisley Suzanne Valadon |

Above: The painting whose title became the name of a movement - - Claude Monet's "Impression, Sunrise."

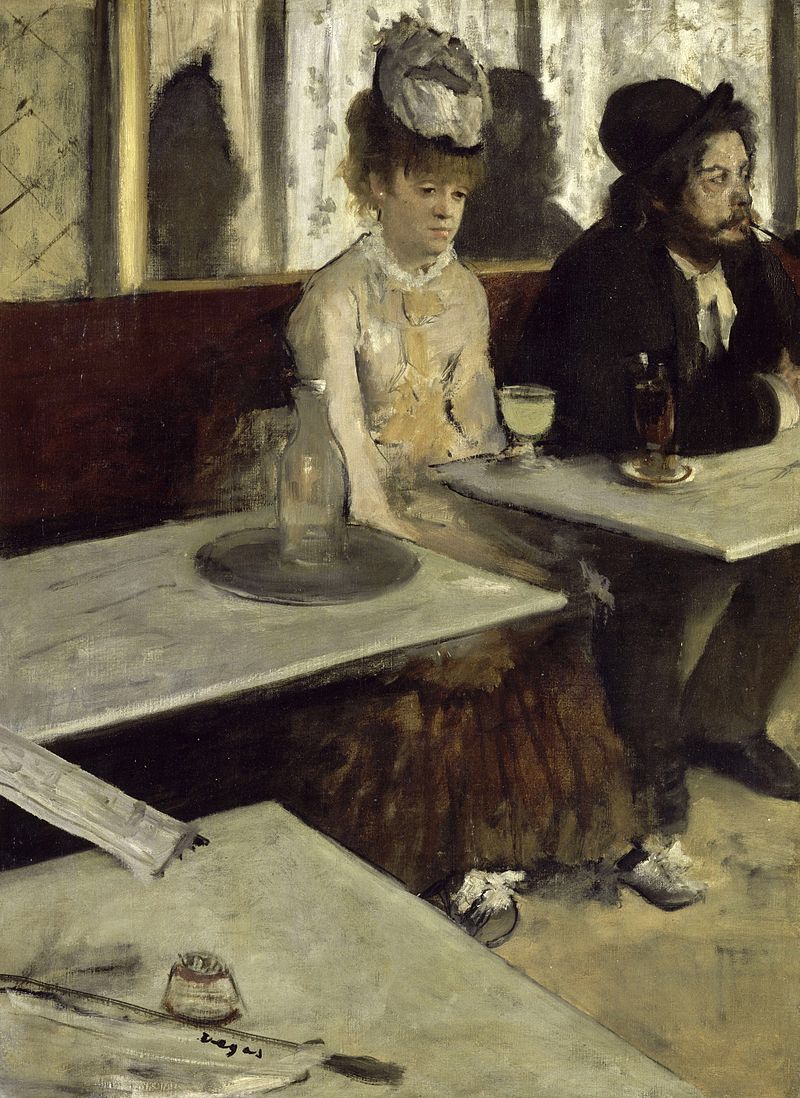

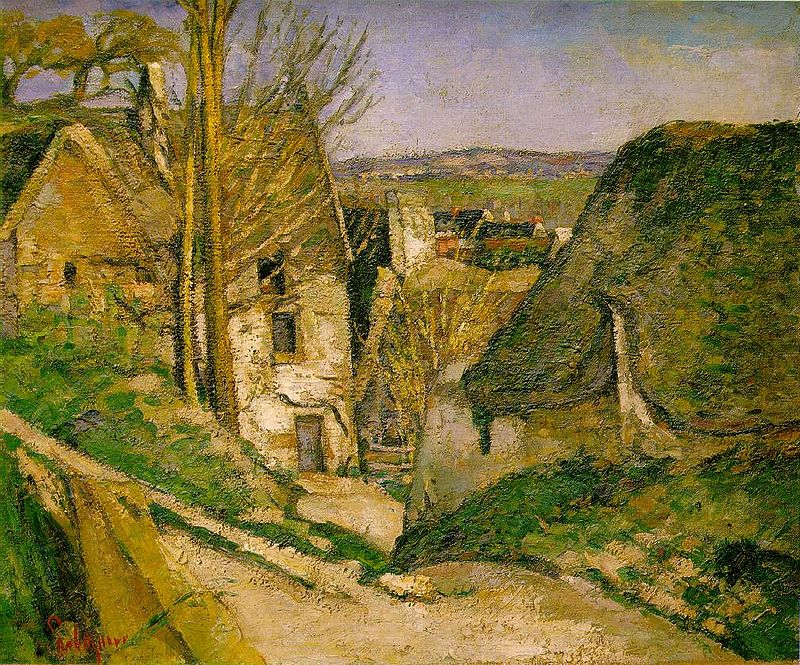

Below; Also exhibited at the First Impressionist Exhibition was Pierre-Auguste Renoir's "The Dancer." The works shown at the First Exhibition highlight that Impressionism encompassed a variety of styles. Above: Edgar Degas' "In The Cafe". Below: Paul Cezanne's "The Hanged Man's House".

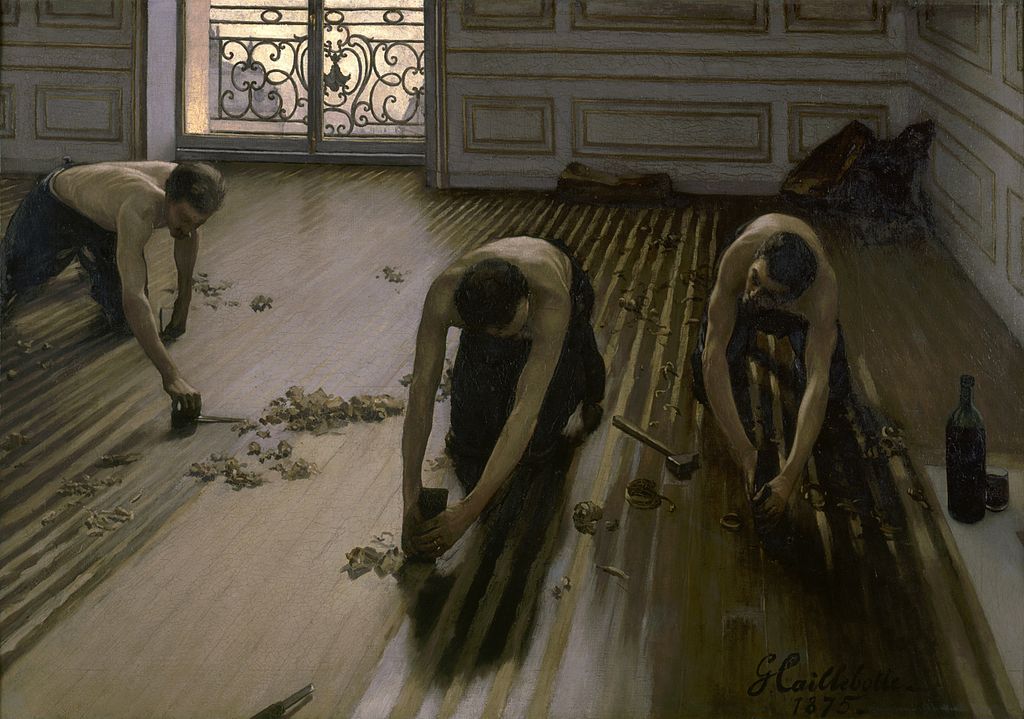

Above: newcomer Gustave Caillebotte's "The Floor Scrapers" was a highlight of the Second Exhibition.

Below: Berthe Morisot's "Hanging Out the Laundry" was also shown at the Second Exhibition. |

Artist appreciation - The Eight Impressionist Exhibitions - page one