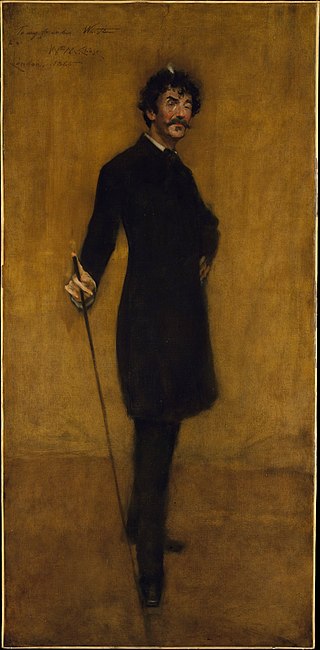

AN APPRECIATION: James Abbott McNeill Whistler Portrait of Whistler by William Meritt Chase Portrait of Whistler by William Meritt Chase

Many tributes can be paid to James Abbott McNeill Whistler. For example, he is one of the father's of modern art, one of America's first great artists and the creator of at least one of the world's best known painters. He as also a unique personality, defying the social conventions of the Victorian world while at the same time carving himself a successful niche in the upper strata of Victorian society. In other words, he was also a forerunner of the modern celebrity.

Career Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1834. However, his family soon moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, the result of a commission given to his father to construct a railroad between St. Petersburg and Moscow. It was there that Whistler received his first instruction in art, beginning with private lessons and then classes at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. This was a very traditional education with much copying of plaster casts of classical statues. While in Russia, the family took two trips to England. On one of these, Whistler's sister Deborah married the English surgeon Francis Seymour Haden, who had learned etching techniques in order to make anatomical drawings and who later would become prominent in the Etching Revival movement. This was probably Whistler's first exposure to printmaking. Haden also gave young Whistler a set of watercolors and took him to see art collections and to hear art lectures. These experiences confirmed Whistler's ambition to become an artist. Following the death of Whistler's father from cholera in 1849, his widow and children returned to the United States. Despite Whistler's artistic ambitions, he followed in his father's footsteps gaining admission to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. However, the flamboyant young man did not graduate due to his poor grades, lack of discipline and insubordinate manner. Following West Point, he obtained positions in the U.S. Geodetic and Coastal Survey offices in Washington. He found this work generally boring until he was transferred to the etching department which made maps and charts. Whistler would embellish his work with drawings in the margins of sea creatures and various other characters. These additions did not please his employers. In 1855, Whistler moved to Paris in order to study art. In addition to studying at the atlier of Marc Charles Gabriel Gleyre, Whistler would study by copying Old Master paintings at the Louvre. He adopted a Bohemian lifestyle and became friends with Gustave Courbet and other artists who were rebelling against the traditional ways of the art establishment. Whistler adopted elements of the Realist School into his art. A few years later, he shifted his base to London. Although he frequently returned to Paris, London would be his primary home for the next 40 years. In 1859, he produced a major work “At the Piano,” a portrait of his sister in black and her daughter in white. Because of its unfinished look, it was rejected for the Royal Academy's prestigious annual exhibition. However, it was subsequently recognized and shown at numerous exhibitions. During this period, Whistler also found success with printmaking. Printmaking had reached its artistic zenith with Rembrandt but subsequently fell out of favor. During the mid-19th century, artists began to rediscover etching as a means of self-expression. Inasmuch as Whistler was well-versed in this medium, he was in a good position to take advantage of its revival. His first important success with this medium was a set of 12 etchings he made of genre and landscape subjects. Although not all the subjects involved France, it is known as the “French Set.” It was followed a few years later by another set of etchings called the “Thames Set” because the subjects were scenes of docks and warehouses along the river in East London. Returning to Paris in 1861, he painted “The White Girl,” a portrait of a woman in a white dress standing in front of a white background. Whistler was interested in the tonal differences. However, critics saw various scandalous meanings in it. In addition, it lacked the polish of an academic painting and so was rejected by the prestigious Paris Salon. The Salon rejected so many submissions that year that Emperor Napoleon III wanted to see the rejected works for himself. Therefore, the Salon des Refuses was organized. Whistler's “The White Girl” caused almost as much of a sensation as Edouard Manet's “Le dejeuner sur l'herbe”. Returning to London, Whistler submitted “The White Girl” to the Royal Academy, which also rejected it. He then showed the painting in private exhibitions with a sign saying “rejected by the Royal Academy.” As a result, the painting became the talk of London and Whistler was famous on both sides of the English Channel. Whistler cultivated the image of a flamboyant artist. He would hold invitation-only Sunday gatherings at his London studio. London's intellectuals as well as the rich and famous came as much to hear Whistler's wit and witness his antics as to see his latest work. Naturally, a demand for Whistler's portraits developed. Whistler's most famous portrait, of course, was not of one of his patrons but of his mother. In 1864, Whistler's very proper and religious mother came to live with him in London. This put something of a damper on Whistler's lifestyle but he soon arranged ways to both accommodate his mother and his various mistresses. One day when a model failed to arrive, Whistler suggested that his mother pose. As usual for a Whistler portrait, this led to numerous sittings. The finished painting received mixed reviews at first but “Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist's Mother” (aka “Whistler's Mother”) became world famous. One of Whistler's patrons was shipping magnate Frederick Leyland. Whistler and Leyland shared an interest in Japanese art and porcelain. Leyland purchased Whistler's “Rose and Silver: The Princess of Porcelain” to be the centerpiece of the dining room for the London townhouse he was having redecorated. This project was not a mere change in the color of the walls but involved such things as installing 15th century Cordovan leather that had once belonged to Catherine of Aragon. As part of this project, Leyland also hired Whistler to give Leyland his thoughts about the shutters and doors for the dining room. While the work was going on, Leyland stayed out of town.. Whistler assumed he had license to do what he wished and totally transformed the dining room with designs based on peacock feathers, gold leaf trim and blue paint over the red leather. The Peacock Room became a masterpiece of Anglo-Japanese art. But when Leyland returned he was outraged and refused to pay Whistler the 2,000 guineas the artist demanded. In the end, Leyland paid 1,000 pounds. Interestingly, the supposedly-outraged Leyland kept the Peacock Room the way Whistler left it. Whistler believed in art for art's sake. He was not interested in producing realistic depictions of events, places or even people or using art to illustrate a story. Rather, his objective was to create beautiful works that like music were artistic in their own right. He focused on tonal harmonies and the arrangement of line. In 1866, while on a visit to Chile, Whistler began a series of paintings that were a forerunner of abstract art. While based on actual scenes, these nocturnal landscapes were quite vague and dream-like. Borrowing a term from music, Whistler called them “nocturnes.” (He also began to use other musical terms to title his works and re-title earlier works). Whistler saw what he was doing as distinct from what other avant garde artists were doing. For example, although he was friends with Claude Monet, he declined Edgar Degas' invitation to exhibit with the Impressionists. He objected to their vibrant colors, often using an almost monochromatic pallet in his paintings. In 1877, one of the nocturnes became the center of a legal battle. “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket” was inspired by a fireworks display over the Thames. Renown art critic John Ruskin hated the work and in his review condemned Whistler for asking “two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face.” Whistler sued for libel. One of the high points of the trial was when Ruskin's layer demanded to know if Whistler was asking two hundred guineas for just two days' labor. Whistler responded: "No, I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime." While the trial afforded Whistler a forum to express his opinions on art and aesthetics, it was a financial disaster. The jury found in Whistler's favor. However, it awarded his only a farthing (i.e. less than a penny) in damages. The cost of the trial on top of various other bills the free-spending Whistler had incurred forced him to sell nearly everything he owned and go into bankruptcy. Fortunately, the Fine Art Society of London, which had backed Ruskin during the trial, commissioned Whistler to do 12 etchings of Venice. Whistler accepted but in typical Whistler fashion went far beyond the commission, doing some 50 etchings, plus watercolors and pastels. His subjects were not just the famous sites of Venice but the backstreets where the tourists rarely go. These works proved quite successful when Whistler returned to London and helped alleviate his financial difficulties. In 1886, Whistler was elected chairman of the Society of British Artists. The next year, on behalf of the Society, he prepared and presented an album including a lengthy address and illustrations to Queen Victoria on the occasion of her Golden Jubilee. The Queen was so pleased that she commanded that henceforth the group would be known as a Royal Society. Whistler continued to work until his death in 1903. In addition to painting, printmaking and drawing, he wrote books, gave lectures and at one point opened his own art school. Personal life Whistler cultivated the image of the flamboyant and eccentric artist. He dressed as a dandy and enjoyed calling attention to himself. He was fond of the outrageous and of displaying his considerable wit and intelligence. He was friends with many other artists and intellectuals including Oscar Wilde, Dante Gabriel Rosetti, Manet and Stephane Mallarme. However, his arrogant manner and overly sensitive nature often led to bitter disputes with close friends. Whistler had many sexual relationships with women. However, his first long-lasting mistress was Joanna Hiffernan, who was the model in “The White Girl” and many other Whistler paintings. Their relationship soured after Hiffernan posed in the nude for Whistler's friend Courbet. His second mistress Maud Franklin also appeared in many of his works. She liked to call herself Mrs. Whistler, and had two daughters by him. However, they were never married. Instead, he married Beatrice Godwin, the widow of architect Edward Godwin who had designed a house for Whistler. She also appears in many of Whistler's works and was an artist in her own right. The marriage was a short but happy one. They were married in 1888 but five years later, she was diagnosed with cancer. Her death in 1896 greatly affected Whistler and his work never again reached the same level. Analysis Whistler was one of the artists who lay the groundwork for modern art. Once you accept that the role of art is not to depict reality but rather is art for art's sake, a work need not have a basis in reality. Thus, the door was opened for complete abstraction. This does not mean that Whistler was entirely in tune with later modern artists. Like Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Whistler was interested in creating beauty. Later artists often focused on ugliness. Indeed, there is a school of thought in contemporary art that champions the notion that a picture cannot be good unless it is ugly. On a more technical level, Whistler had a great ability to convey much with a little. He was able to reduce a scene to its essentials with a minimum of marks and tones. Along the same lines, his portraits were able to capture and convey the essence of the person. |

Above: An internationally famous image: "Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist's Mother" a.k.a. "Whistler's Mother".

Below: Whistler created controversy with "The White Girl" (lte retitled "Symphony in White No. 1). Whistler's dreamlike landscapes were a forerunner of modern art. Above: Arrangement in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge".

Below: "Nocturn in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket" triggered one of art's most significant lawsuits. Above: The centerpiece of the Peacock Room - "Arrangement in Pink and Rose: The Princess from the Land of Porcelain."

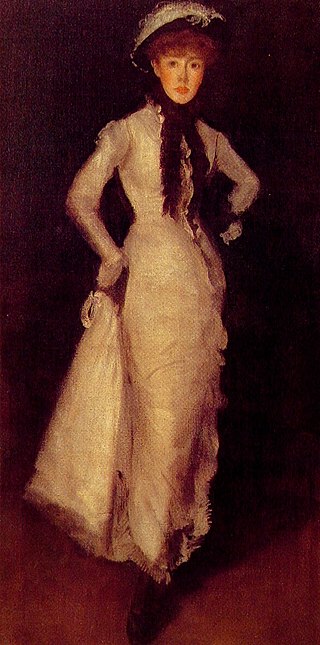

Below: Whistler also became known for his full-length portraits of figures in London society. "Nocturne in Pink and Gray, Portrait of Lady Meux" Two important figures in Whistler's life. Above: Whistler's long time mistress and mother of two of his children Maud Franklin; "Arrangement in Black and White."

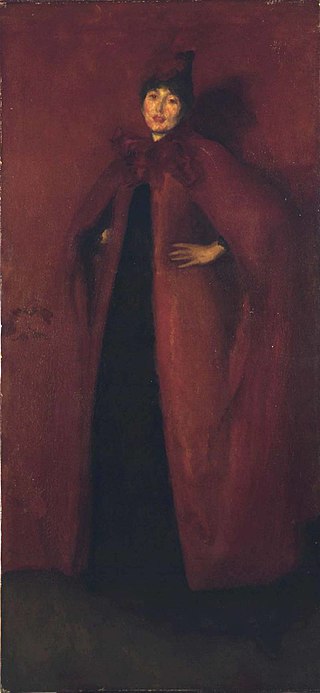

Below: Whistler left Maud to marry Beatrice Godwin; "Harmony in Red Lamplight", |

Artist appreciation - James Abbott McNeill Whistler