AN APPRECIATION: Thomas Eakins Thomas Eakins, Self-portrait. Thomas Eakins, Self-portrait.

Thomas Eakins was an American painter, photographer and sculptor in the second half of the 19th century. In a quest for realism and truth, he developed a unique style.

Eakins was born into a middle class Pennsylvania family on July 22, 1844. His father Benjamin Eakins was a teacher of penmanship and a calligrapher. From him, Thomas would learn about line, perspective and the patience needed to do this precise work. In addition, it was a close-knit family in which open exchange between parents and children flourished. The family moved to Philadelphia in 1846. Thomas would spend most of his life in that city. He attended Central High School where did well in art. Having paid for a substitute to fight in the American Civil War, Eakins continued his study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in 1861. The school's program was very conservative and Eakins spent much time making drawings of plaster casts of classical statues. It was not a program that Eakins enjoyed. Nor was he inspired by the historical paintings of his chief instructor Christian Schussele. Much more to his taste were his studies at Jefferson Medical College. Interested in learning about human anatomy, Eakins attended not only lectures but also dissections of human bodies. For a time, he thought of becoming a surgeon but decided to use his knowledge of anatomy in creating realistic art work. In 1866, he journey to Paris, France, then the capital of the art world, to study at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux Arts. His primary instructor was Jean Louis Gerome, whom Eakins maintained a correspondence even after he returned to the United States. Eakins also briefly studied with Leon Bonnat. Eakins did not care for the academic style of art championed by the Ecole des Beaux Arts, which he regarded as overly sentimental and artificial. Also, like the Impressionists who were also working in Paris at this time, he was interested in depicting modern people. However, while Eakins and the Impressionists shared similar goals, their approaches were quite different. It appears that Eakins had no interaction with Edouard Manet, Claude Monet or the other young rebels of that era. After studying in Paris, Eakins traveled to Spain in 1869. There, he was particularly impressed by the work of Diego Velasquez. Returning to Philadelphia in 1870, Eakins resumed residence in the family home. His father agreed to turning the upper floor of the house into an art studio. Eakins began a series of works involving athletics. In particular, he focused on men rowing sculls on the rivers near Philadelphia. In the reverse of the usual procedure, Eakins would make an oil painting sketch in preparation for the final picture that would be done in watercolors. At the same time, Eakins produced a series of portraits of women in thoughtful or reflective moods. These were often dark compositions involving the use of chiaroscuro. He often turned to his three sisters and his fiancée to pose for these works. Combining his interest in art with his interest in science, Eakins began a major work in 1875. It it, Eakins depicted Dr. Samuel Gross, who taught at the Jefferson Medical College, giving a lecture to a group of surgeons while he dissected a corpse. Rembrandt's depiction of a similar scene in “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulip” had helped to build the Dutch master's reputation and perhaps Eakins thought a modern version of the subject would draw attention to him. “The Gross Clinic” succeeded in drawing attention to the young, unknown artist but not all of the attention was desirable. Eakins artistic skill was recognized by the critics. However, the painting was exhibited separately from the other artwork that appeared at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia because it was considered too shocking to be viewed by ladies and others of a sensitive nature. Still, Eakins was beginning to find success. In 1877, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of President Rutherford B. Hayes - - a project Eakins found difficult because of the sitter's inability to remain still. At the same time that he was pursuing a career as a professional artist, Eakins pursued a career as an art teacher. It began with an unpaid position as an instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in 1876. In 1879, Eakins was appointed Professor of Drawing and Painting at the same institution. This was followed shortly thereafter by appointments as Assistant Director and finally as Director. Eakins radically changed the curriculum. The emphasis on drawing from plaster casts was greatly reduced. Instead, emphasis was placed on drawing from live models and the study of anatomical structure, form and perspective. Furthermore, classes featuring live, nude models were open to both men and women. Like his instructor Gerome, Ekins believed in teaching by example and giving the students considerable freedom to find their own way. It was a quite liberal and advanced approach. While many students approved of the new teaching methods, others found them shocking. Among those who found Eakins' methods shocking were the members of the Academy's Board of Directors. When Eakins removed the loin cloth from a male model during a class in which female students were present, it was too much for the Board. It demanded that Eakins cease using such methods or resign as Director. Eakins refused to change and resigned. Some 38 students left the Academy in protest. They formed the Art Students League of Philadelphia modeled on the Art Students League of New York. Eakins accepted their invitation to teach there. He also taught at a number of other schools including the Art Students League in New York, the National Academy of Design and the Artists Guild in Washington D.C. Eakins was shaken by his experience at the Pennsylvania Academy. His personal life had suffered a series of blows since his return from Paris. His mentally ill mother had died in 1872. His fiancée, Katherine Crowell, had died in 1879 and his favorite sister Margaret died in 1882. His brother-in-law accused Eakins of unspecified “ungentlemanly conduct” and successfully demanded that Eakins be expelled from the Philadelphia Sketch Club. This led Benjamin Eakins to throw both the brother-in-law and his daughter out of the family house. It was a family rift that never healed. On a brighter note, in January 1884, Eakins married the painter Susan Hanah Macdowel, who was one of his former students. Her father, William H. MacDowell, was a Philadelphia engraver who was fond of new ideas. Thus, not only did Susan have a similar background as Eakins, she was attuned to his advanced thinking. Both she and her father posed for Eakins paintings and photographs. For a short time, they had their own home but eventually moved into the Eakins family home. That same year, Eakins worked with Eadweard Maybridge who was using photography to study horses and people in motion. Eakins was well-versed in both human anatomy and had also studied equine anatomy. While Maybridge was interested in using the camera as a scientific tool, Eakins was interested in it as a tool for furthering art. Eakins took numerous photographs during the course of his career. Eakins photography was not free from controversy. He shocked students by using photos of nude men and women in his classes. He was accused of having traced photographic images onto his canvases in order to obtain more detail - - a charge he repeatedly denied. His photos of naked men are still cited as evidence that he was bi-sexual. Following his forced resignation from the Pennsylvania Academy, Eakins made a long journey to North Dakota. There, he made sketches and took photographs of cowboys and western life, which were later used as the basis for paintings. From 1887 on, Eakins concentrated almost exclusively on portraiture. His goal was to produce realistic depictions of the character of the people who sat for him. Thus, he did not attempt to flatter his sitters or accede to their notions of how they should be portrayed. As a result, he received few society commissions and some of his commissions were rejected when the sitter saw the final product. Still, Eakins did receive commissions; chiefly, from scientists, intellectuals and, although he was agnostic, from members of the clergy. He also received a commission to design statues of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. In addition, he was made a full academician of the National Academy of Design in 1902 and one of his paintings earned a prize from that body in 1905. Along the same lines, Eakins won a gold medal at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. When the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art awarded him a gold medal in 1903, Eakins, recalling how he was forced from that institution, accepted the medal but took it to the mint and had it melted down. In 1910, Eakins' health began to deteriorate and he produced few works subsequently. He died on June 26, 1916 of apparent heart failure. |

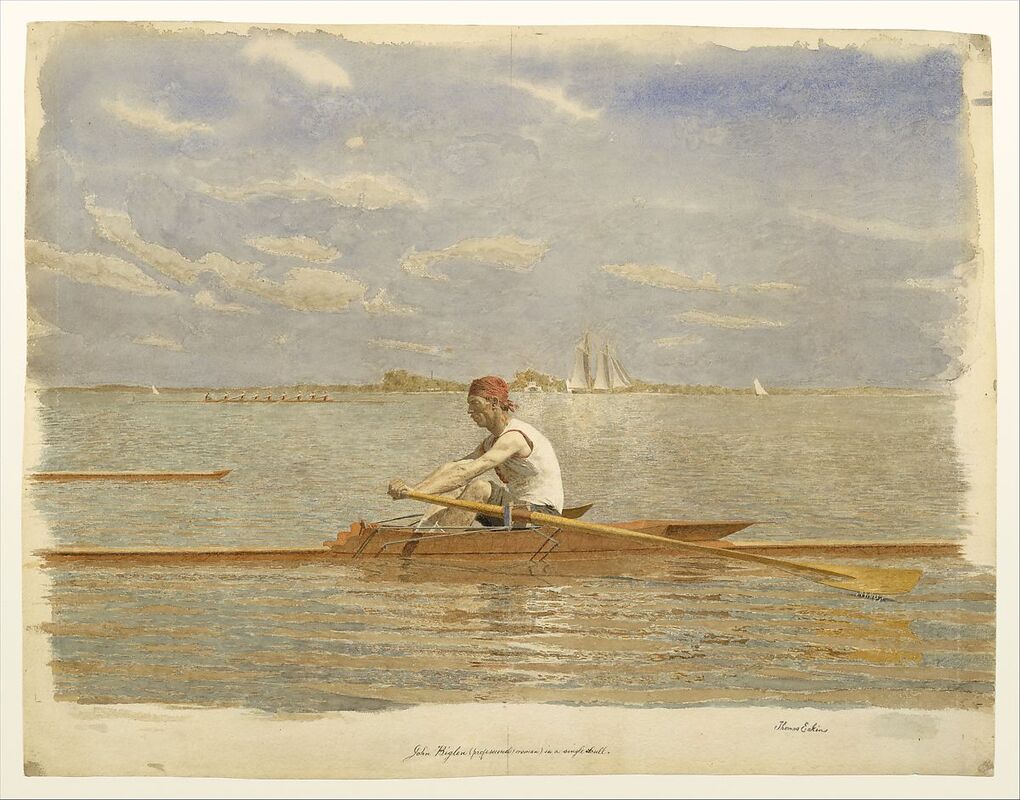

Upon his return from studying in Paris, Eakins did a series of paintings of men rowing. Above: Max Schmitt in a Single Scull. Below: John Biglin in a Single Scull, a watercolor.

Above: Eakins controversial "The Gross Clinic."

Below: "The Concert Singer." In order to ensure that the painting was anatomically accurate, Eakins had the subject sing so that he could study the movement of her throat muscles. Eakins was engaged to Katherine Crowell (above) for seven years. After he death from meninges, Eakins married painter Susan MacDowell (below).

Above: "The Chess Players."

|

Artist appreciation - Thomas Eakins