AN APPRECIATION: Edouard Manet Manet by H. Fantin-Latour Manet by H. Fantin-Latour

Edouard Manet never exhibited with the Impressionists and he declined to call himself an Impressionist. However, the Impressionists considered him a hero and without Manet, it is unlikely that Impressionism would have ever succeeded. In return, the Impressionists influenced Manet's work, allowing it to reach even greater heights.

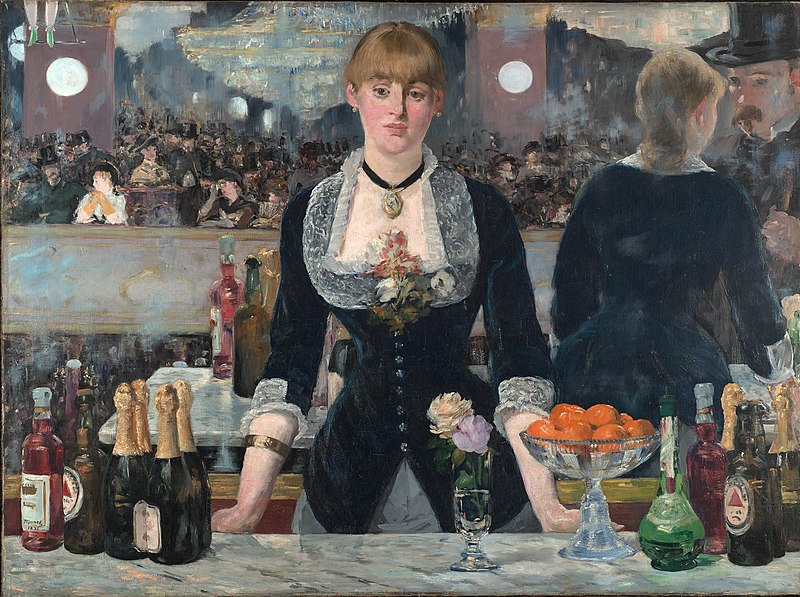

Career Manet was born in 1832. His family was affluent and well-connected. His father was a judge and his mother was the god-daughter of the Swedish king Charles XIV John. (The king, formerly called Jean Bernadotte, was born a Frenchman and had achieved fame as a Marshall of the Empire under Napoleon I. This led to his being asked to assume the Swedish throne). The profession of law was something of a tradition in the Manet family and Manet's father hoped his son would also enter the law. His maternal uncle, however, encouraged young Edouard's interest in art, taking him to see the collections in the Paris museums and mansions. When the boy reached his late teens, his father still hoped that Edouard would pursue a respectable profession suitable for someone of his class. If it was not to be the law, then a career in the navy would be an acceptable compromise. However, Edouard was too old to enter the naval academy unless he had experience at sea. Therefore, he signed on to a training ship and made a voyage to Rio de Janeiro in 1848 But a naval career was not to be as Edouard twice failed the entrance examination for the navy. With his family's acquiescence, Manet now began to study art. He enrolled in the studio of Charles Couture. However, Manet did not care for Couture's academic approach to art and Couture did not care for Manet's avant garde style. Much more satisfactory to Manet was the time that he spent in the Academie Suisse, a free studio, where Manet could paint as he wished. Perhaps the most educational part of his studies, however, was when he went to the Louvre to copy the works of the Old Masters. He was particularly influenced by the works of the Spanish artists Velazquez and Goya. In 1856, Manet felt ready to open his own studio in Paris. It was a time of great change. Emperor Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann were in the process of replacing the old medieval city with a modern yet beautiful city. Meanwhile, the industrial revolution was producing both prosperity and more leisure time for the growing middle class. Writers and intellectuals thrived in this climate. Manet, heeding the call of his friend the writer Charles Baudelaire, set out to be an artist who recorded this modern life. But before Manet lay a formidable obstacle. If an artist wanted to be successful in the art world at that time, he or she had to show his work at the Paris Salon – the annual official government art exhibition. The best works shown at the Salon were purchased by the government. More importantly, exhibiting at the Salon was seen as a stamp of approval. If an artist's work was shown at the Salon, collectors and other purchasers knew that it must be good. Not just anyone could exhibit at the Salon. A jury not only decided what pieces could be shown but how they were hung and which works would receive prizes. The jury was made up of academicians from the Academie des Beaux Arts (the “Academy”), the official art school, and they were devoted to the principles taught at the Academy. The juries hated Manet's work for two reasons. First, Manet painted scenes of real people involved in modern life. The Academy believed that there was a hierarchy to art with history painting at the top. By this they meant, scenes from the Bible or pictures inspired by Greek and Roman mythology or a glorified image of a great battle. Scenes of modern life were impossibly vulgar. Second, Manet's technique was all wrong. In a good painting, there should be no signs of brush work, everything should be smooth and varnished. Manet's brush strokes were clearly visible, the colors were wrong and the images were cropped like a photograph. Despite this hostility, two of Manet's works were shown in the Salon of 1861. However, in 1863, the jury rejected a major work by Manet “Déjeuner sur l'herbe” - a scene in which a nude woman and a partially-dressed woman are having a picnic with two fully-dressed men. The jury rejected so many submissions that year that complaints were made to the Emperor. Napoleon III decided that he would like to see the rejected works and a Salon of the Rejects (Salon des Refuses) was organized. “Déjeuner sur l'herbe” was one of the works shown at that exhibition and it caused a scandal that rocked Paris. Most critics and the public condemned the work but a few writers including Emile Zola, were impressed. Manet was not intimidated by the scandal. For the 1865 Salon, he contributed a painting of a female nude. The jury accepted it but “Olympia” caused an even greater scandal than before. It was clearly the painting of a modern woman who was most likely a courtesan not an inspiring image of a Greek goddess. Furthermore, the pale colors and unfinished look of the painting irritated academicians. However, once again, Manet had a small group of supporters. Upon learning that an academic jury was going to exclude his works from the Universale Exposition of 1867, Manet used an inheritance from his father to erect a pavilion across from one of the entrances to the Exposition. Inside, Manet exhibited 50 of his paintings. Once again, there was a split of opinion with most critics hostile but also a growing number of supporters. Manet was by now a hero to the young avant garde artists of Paris. In the evenings, he was the center of a group including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Frederic Bazille and Camille Pissarro that met at the Cafe Guerbois to socialize and talk about art. There was a suggestion that they should hold their own independent exhibition but nothing came of it. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 intervened. Manet elected to stay in Paris and served as an artilleryman in the National Guard during the Siege of Paris. Following the war, the juries at the Salon became even more restrictive. Anything avant garde was viewed as being of the same ilk as the unpopular Paris Commune that had immediately followed the war. Consequently, there were more rejections for Manet and his friends from the Cafe Guerbois. Championed by Pissarro and Degas, the idea of an independent group exhibition resurfaced. By 1874, most of the group, including Manet's friend Berthe Morisot, had decided to go ahead with the project. They invited Manet to participate but he told Degas “I prefer to enter the Salon by the front door.” As a result, Manet did not participate in that exhibition or any of the seven subsequent Impressionist exhibitions. This did not isolate him from the criticism that was hurled against the Impressionists in the press as he was seen as their leader even if he did not participate in the exhibitions. Instead, he continued to submit works to the Salon. At first, he found some success. Officialdom, critics and the public became reconciled to his style. “Le Bon Bock” shown at the Salon in 1873 received unanimous praise. But then Manet's style changed. Urged to do so by Morisot, he tried plein air painting. His palette became lighter and the colors brighter. He went on painting expeditions with Monet and Renoir. In short, he began to incorporate the Impressionist style into his work. Inasmuch as the Impressionists were condemned by the art establishment, Manet again felt the sting of public criticism and Salon rejections. By the 1880s, the wind had shifted again. His submission to the 1881 Salon was not only accepted but won a medal. In 1882, the French government awarded Manet the star of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Manet, however, was a very sick man. Syphilis and rheumatism made it difficult for him to move. However, Manet had one last great work in him. “The Bar at the Folies Bergere” was the last in the line of Manet's paintings of Parisian nightlife. It was accepted and shown at the 1882 Salon. In the Spring of 1883, gangrene appeared in Manet's left foot. It was agreed amputation was necessary. However, the operation was too late to stop the spread. Manet died on April 30, 1883. Private life We often think of the time when Manet lived as being very constrained. In England, Queen Victoria was on the throne setting an example of prudish morality for the world. However, in Paris at this time, approximately one third of the births were out of wedlock. Although Manet was the center of a circle of Bohemian artists and forward-thinking intellectuals, his appearance was unlike the popular image of the struggling artist. He took great pride in his dress, wearing fashionable outfits including a top hat, long coat, yellow gloves and bright pantaloons. Manet loved the Parisian nightlife. In addition to the Cafe Guerbois, he was often seen in fashionable restaurants and cafes. He went to the opera and the theater. He observed what was happening on the new boulevards of Paris. Following his father's death, Edouard married Susan Leenhoff. She had entered Manet's world more than 10 years before when she was hired by Manet's father to give piano lessons to his boys. It is also likely that she became Manet's father's mistress. Consequently, it is unclear whether her son born in 1852 was Manet's son or his father's son. In any case, Leon, who was presented as Susan's brother, was the subject of numerous works by Manet as was his mother. Manet painted many women either in portraits or as models in figure paintings. In addition to being famous Manet had charm and good looks. As a result, well-known actresses and celebrities of the day wanted him to do their pictures. One of his favorite models was Victorine Meurand who appears in “Dejuner sur L'Herbe” as well as “Olympia.” She later became an accomplished artist. Along the same lines, Manet painted a portrait of his only formal pupil, Eva Gonzales, who also became an artist. Manet's relationship with Berthe Morisot remains shrouded in mystery. They were introduced by Henri Fantin-Latour in 1860 when both were copying paintings at the Louvre. They were of similar backgrounds and both were extraordinary artists. A close bond was formed that continued until Manet's death. She married Manet's younger brother Eugene but it has been speculated that this may have been a marriage of convenience. In any case, the way Manet depicted her in the numerous paintings and drawings that he did of her, indicate that she was someone special. Analysis Manet is a major figure in the history of art. By breaking with the conservative academic tradition that dominated the art world, he opened the door to different approached to art thus giving artists greater freedom. If he had not endured the criticism that was hurled against him not only would there have been no Impressionism but there would not have been the various art movements of the 20th century. Leaving aside his historical importance, Manet can be admired for several reasons. He has sometimes been referred to as a Realist but he was not a photo-realist. Indeed, his works are less visually realistic than the academic paintings he shunned. He distilled images to their essence, indicating the essential lines and shapes with an economy of brush-work. He also made clever use of geometric shapes. For example, in “Corner of a Cafe Concert” the main figure is framed by a series of rectangles These represent the area around the cafe stage but they also form a geometric design foreshadowing the modern art of the next century. Manet's choice of colors in his earlier work is somewhat lackluster. However, once he adopted the Impressionist palette, his choice of colors was on a par with Monet and Renoir. See our profiles of these other Impressionists and members of their circle.

Frederic Bazille Eugene Boudin Marie Bracquemond Gustave Caillebotte Mary Cassatt Paul Cezanne Edgar Degas Henri Fantin-Latour Paul Gauguin Eva Gonzales Armand Guillaumin Claude Monet (Part I The Early Years) Claude Monet (Part II High Impressionism) Claude Monet (Part III The Giverny Years) Berthe Morisot Camille Pissarro Pierre Auguste Renoir Alfred Sisley Suzanne Valadon Victor Vignon |

Manet establishes himself as a painter of modern life - "Music in the Tuileries Gardens" (above).

Two scandalous early Manet masterpieces: “Déjeuner sur l'herbe” of "The Luncheon on the Grass" (above) and "Olympia" (below).

Manet influenced the Impressionists but by the 1870s, the Impressionists had clearly influenced Manet's style. Above: "The Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil." Below: "The Monet Family in their Garden at Argenteuil."

Above: "The Railway"

Below: "The Bar at the Folies-Bergere." Two paintings in which Manet's wife, Susan Leenhoff was the model: "The Reading" (above) and "Woman With A Cat" (below).

Above and below: Two portraits of Manet's friend the artist Berthe Morisot.

Above: "The Corner of the Cafe Concert."

|

Artist appreciation - Edouard Manet