AN APPRECIATION: Mary Cassatt Portrait of Cassatt by Degas Portrait of Cassatt by Degas

One of the reasons that the Impressionists have had such a strong influence on art is that the group included so many strong artists. While Mary Stevenson Cassatt was not one of the original Impressionists, she became a key member of the group, participating in most of their later exhibitions. Her work renewed the group's vitality and strengthened the figure painting dimension of Impressionism. Its appeal continues even after more than a century since its creation.

Career Cassatt was born on May 22, 1844 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. Her family was prosperous and well-connected. It had been in America since colonial days. Within a short time after Mary's birth, her father left banking in order to become mayor of the town. In 1853, the family moved to Heidelberg, Germany so that her eldest brother Alexander could study engineering. However, the family returned to the United States following the death of another brother in 1855. At an early age, Mary determined that she wanted to have a career and that art was her vocation. Therefore, despite family objections that this was not a proper pursuit for a woman of her class, she enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. The school was considered progressive in that it allowed women students. However, the approach to teaching art was similar to the conservative European art academies with the students spending much time drawing plaster casts of ancient statues and copying poor quality copies of oil paintings. Mary soon became dissatisfied with the Academy's approach and longed to go back to Europe where she could study the work of the old masters firsthand. However, for a young woman of her class, it was unthinkable that she should undertake unchaperoned independent study. Consequently, she had to wait until 1866 for her parent to agree to take her to Europe and make arrangements with friends of the family living there that would satisfy Victorian conventions. Women were not allowed to enroll in the Academie des Beaux Arts, the prestigious official art school in Paris. Therefore, Mary persuaded one of the instructors, Jean-Léon Gérôme, to give her private lessons. She also took a class in the studio of the fashionable painter Charles Chaplin. However, independently, she made the focus of her studies copying the works of the masters in the Louvre. At the same time, Cassatt became interested in the contemporary art that was flourishing in Paris. Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet were causing scandals by producing art that challenged the prevailing principles of the Academie des Beaux Arts. She found inspiration in the work of both artists. When the Franco-Prussian War erupted in 1870, Cassatt's family demanded that she return home. Dutifully, she did so, taking up residence in the family home. Her father, who did not see the point in Mary's artistic efforts, paid her living expenses but refused to pay for her art supplies. Similarly, when the war in Europe ended, he refused to pay for another trip to Paris. Cassatt decided that she would earn the money needed to continue her career as an artist herself. To this end, she persuaded the Roman Catholic Bishop of Pittsburgh Michael Domenec to commission her to make copies of two works by Correggio located in Parma, Italy. As a result, accompanied by her mother, Cassatt sailed to Italy. After studying the works of the Italian masters, she traveled to Spain to study the Spanish masters. Meanwhile, one of the paintings she had submitted was accepted for inclusion in the Paris Salon of 1872. The Salon was a prestigious exhibition, which dominated not only the French art world but influenced the art establishments throughout the world. Cassatt's painting received good reviews and was purchased. She was now a professional artist. Settling in Paris in 1874 in an apartment that she shared with her sister Lydia, Cassatt became part of the Parisian art world. Although she had some success submitting paintings for the annual Salons, she became increasingly frustrated by the process. The juries would only accept conservative works that met with the principles taught by the Academie des Beaux Arts. Inasmuch as she was becoming increasingly inspired by avant garde contemporary art, the friction grew between her work and the dictates of the Salon. In 1874, a group of young artists who were similarly dissatisfied with the Salon, staged their own independent exhibition. The critics mocked their work calling them “Impressionists,” after the title of an almost abstract painting by Claude Monet that they thought was particularly objectionable. As a proper young lady, Cassatt could not frequent the cafes where these young artists socialized and debated art but she did see their work at exhibitions and galleries. Cassatt was particularly inspired by the work of Edgar Degas. She was walking along the Boulevard Haussmann in 1875 when she saw one of Degas' pastels in a shop window. "It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it." Although the two were yet to meet, Degas was similarly impressed by Cassatt. Upon seeing one of her works at an exhibition, Degas remarked “That is genuine. There is someone who feels as I do.” When Cassatt and Degas did meet, they formed a close association. This included not just working with each other on artistic projects but socializing. Both had strong opinions that they did not hesitate to state and so there were quarrels and times when they did not see each other. However, Cassatt was always in awe of Degas. At Degas' insistence, Cassatt was invited to participate in the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879. She eagerly accepted. Although there was some criticism of her work, her paintings were generally well-received. She used her earnings from the exhibition to purchase a work by Degas and a painting by Monet. Cassatt would go on to participate in all the remaining Impressionist Exhibitions except the Seventh Exhibition. She decided to forego that exhibition in order to support Degas who was boycotting it because the group excluded certain artists that he wanted to include. She was also represented in an exhibition in New York of Impressionist paintings staged by the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1886. In 1877, Cassat's parents moved to Paris, which put Mary's independent existence on hold. With a subsidy from her brother Alexander, who had become President of the Pennsylvania Railroad, the family lived comfortably with summers in the country. However, Cassatt's artistic production during this period was limited because she had to spend much time nursing her parents and her sister when they became terminally ill. Nonetheless, Cassatt continued to produce art. For example, together with Degas and Impressionist Camille Pissarro, she worked on a venture to produce a journal of prints. Although the publication never came about, Cassatt became a skilled print-maker as a result of this project. Her prints were showcased in her first one-woman show held at the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1891. The works also reflected her interest in Japanese prints. The next year, Cassatt was asked to do a mural for the Women's Pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. This large work on three panels was an allegorical depiction of modern women. It was regarded as a great success but it is believed that the work was destroyed when the Fair ended. By the turn of the century, Cassatt was an established successful artists. Indeed, in 1904, she was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. However, despite a number of trips home, she was still less well-known in America than she was in France. In 1915, she supported an exhibition in support of women's suffrage. It was organized by her long-time friend Louisine Havemeyer and featured works by Cassatt and Degas. Cassatt's health had already begun to deteriorate. By 1911, she had been diagnosed with diabetes, rheumatism, neuralgia, and cataracts. She had a series of operations for the cataracts but by 1921, she was nearly blind. She died in 1926 at the country house that she had bought with the earnings from the sale of her works. Private life Cassatt never married. She decided early on that marriage would interfere with her desire to have a career. She often said that she was married to her art. There has been considerable speculation about her relationship with Degas. However, inasmuch as she burnt his letters to her before her death, there is no conclusive evidence. The two were from similar upper class backgrounds and had many common interests so it is not surprising that they would become friends. Furthermore, it would have been against the mores and beliefs of their class for two unmarried people to have had a romantic affair. Still, romantic friendships were quite common among the Victorians. Cassatt idolized Degas, adopted many of his ideas and techniques and promoted him to her friends and colleagues. Degas, who cultivated the image of a misanthropic bachelor, invited her to show with the Impressionists, did numerous portraits of her, introduced her to pastels, etching and Japanese prints, and helped her with her art. Indeed, it is believed that he even painted part of the background in one of her early masterpieces. The two had a very close relationship. Cassatt and Degas fell apart after a quarrel over the Dreyfus Affair, which rocked turn-of-the-century France. She, nonetheless, was immensely sadden by Degas' death and attended his funeral in 1917. It is also believed that James Stillman, retired president and chairman of the National City Bank of New York, may have proposed to Cassatt. She advised him on the art collection for his Paris mansion and he accompanied her on a vacation to the South of France in 1912. Analysis Mary Cassatt overcame three formidable obstacles to become a great artist. First, she had to overcome the prejudices and limitations that society placed on women. In those days, women were expected to marry and raise children. They were not supposed to have a profession. Thus, Cassatt had to overcome both the laws and mores designed to keep women in their place as well as the self-doubts that such constraints plant in the mind of the person being oppressed. Cassatt strongly believed in equal rights for women. For this reason, she objected to being termed a “woman artist.” She wanted to be considered an artist and judged on equal terms with both her male and female colleagues. Second, Cassatt was an American. At that time, America had very little artistic tradition and had produced few great artists. The art world did not expect much from Americans. People like John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler and Mary Cassatt changed that. Third, Cassatt was interested in what was then avant garde art. The critics and the art establishment were arrayed against this art. Cassatt was instrumental in opening the door. Cassatt is best known for her depictions of women with children. Depictions of a mother and child had been a favorite subject of European artists for centuries before Cassatt but it was usually within a religious context. Cassatt's depictions were both secular and contemporary. Although she had no children herself, Cassatt clearly had something to say about such relationships. Her works do not seek to glorify the relationship or to promote it as the proper role for women in society but rather seek to convey some of the emotions involved in such relationships. What makes them popular is that they speak in genuine terms. Two factors explain the fact that Cassatt returned to this subject again and again. First, in the Victorian world, woman were all but limited to domestic life. Cassatt was depicting the world she knew. Second, her mentor Degas preached that an artist should return to the same subject numerous times in order to explore it fully. While Cassatt was a card-carrying member of the Impressionist group and a disciple of Degas, her art is unique and easily distinguishable from the art of her colleagues. It is original; she was not just tagging along. Cassatt's art evolved over the course of her career. Starting out with an academic base, she incorporated ideas from other artists, including the old masters, Manet, Degas, and Japanese print-makers, as she became exposed to them. She did not copy their approaches but rather incorporated elements and/or techniques into her own art. This helped to keep,her work vital over time. Cassatt also played an important role as a collector. Like Gustave Caillebote, she purchased works by her Impressionist colleagues. This enabled the group to carry on with their art as Monet, Pissarro and Pierre-Auguste Renoir had no independent means and were living in poverty during the early part of their careers. She even provided money to the Durand-Ruel gallery when it was facing bankruptcy in 1882. That gallery was an early supporter of the Impressionists and was key to promoting their work both in France and in America. Along the same lines, Cassatt encouraged her friends to collect works by the Impressionists. Her friends included people of influence. Consequently, Cassatt's action not only provided revenue to her impoverished colleagues but also promoted their art so that it became appreciated by the public. Inasmuch as the critics and the art establishment were hostile to the Impressionists, Cassatt was sailing against the wind in these efforts. Interestingly, Cassatt did not appreciate the avant garde work that followed Impressionism. She did not care for the work of the Fauves or Cubists. Indeed, she was critical of the later work of some of her Impressionists colleagues. This included Monet's waterlillies series, which she referred to as “decorations” When Cezanne's Post-Impressionist works became popular, she advised her friend Louisine Havermeyer to sell the Cezanne's she owned because his popularity was only a passing fad. In her view, these artists had simply gone off in the wrong direction. This does not mean that Cassatt was only interested in self-promotion. She advised her friends to purchase works by other artists outside of her circle. As a result, some of the finest private collections of art were assembled. For the most part, these collections were later donated to museums and significantly strengthened public access to art in America. |

Above: "Lydia in a Loge Wearing A Pearl Necklace" which Cassatt showed at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition, her first time showing with the group.

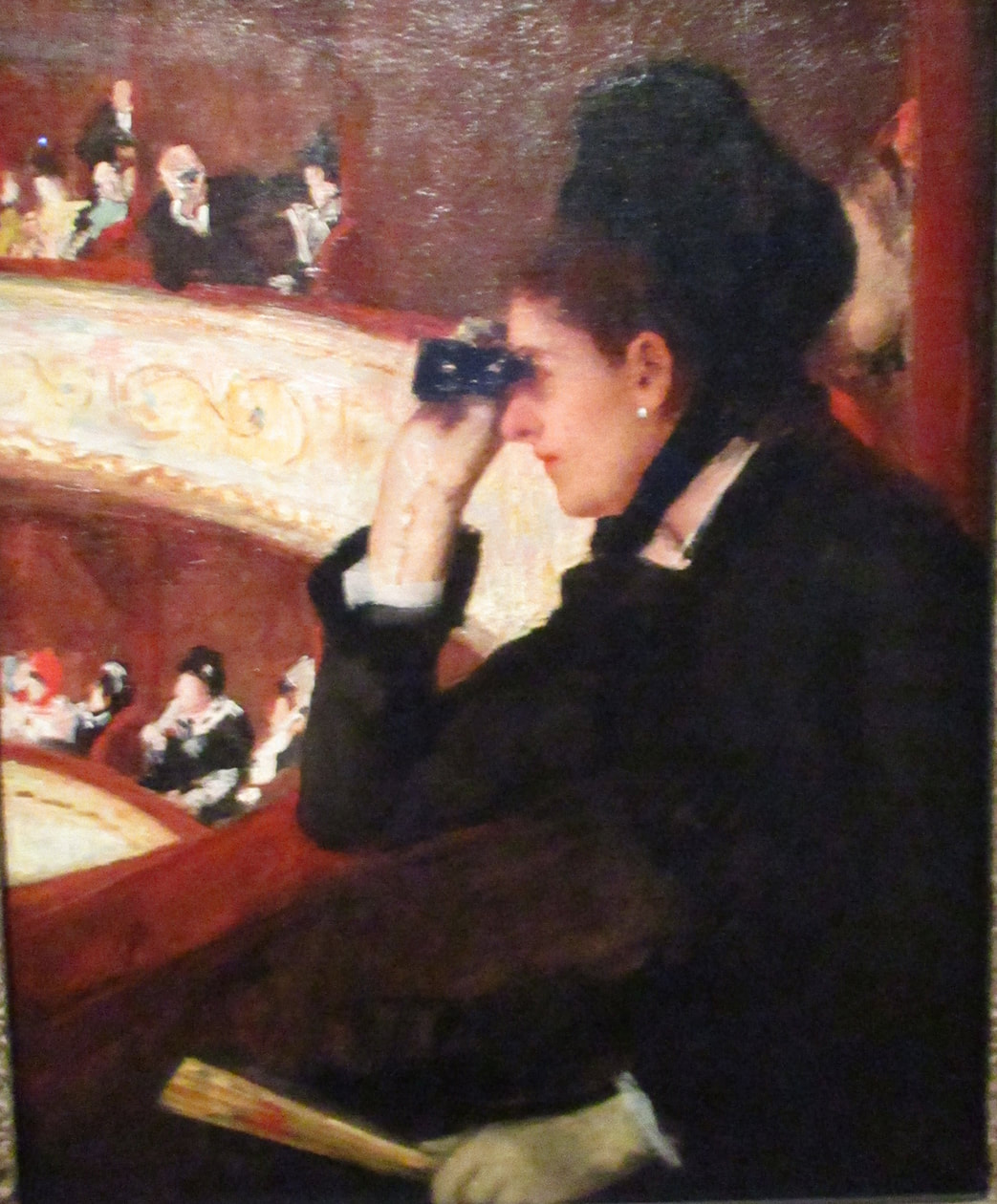

Below: Cassatt returned to the subject of people in a theater audience several times including "A Woman in Black at the Opera." Above: "Young Girl in a Blue Armchair." It has been suggested that Cassatt's friend and mentor Edgar Degas may have painted parts of the background.

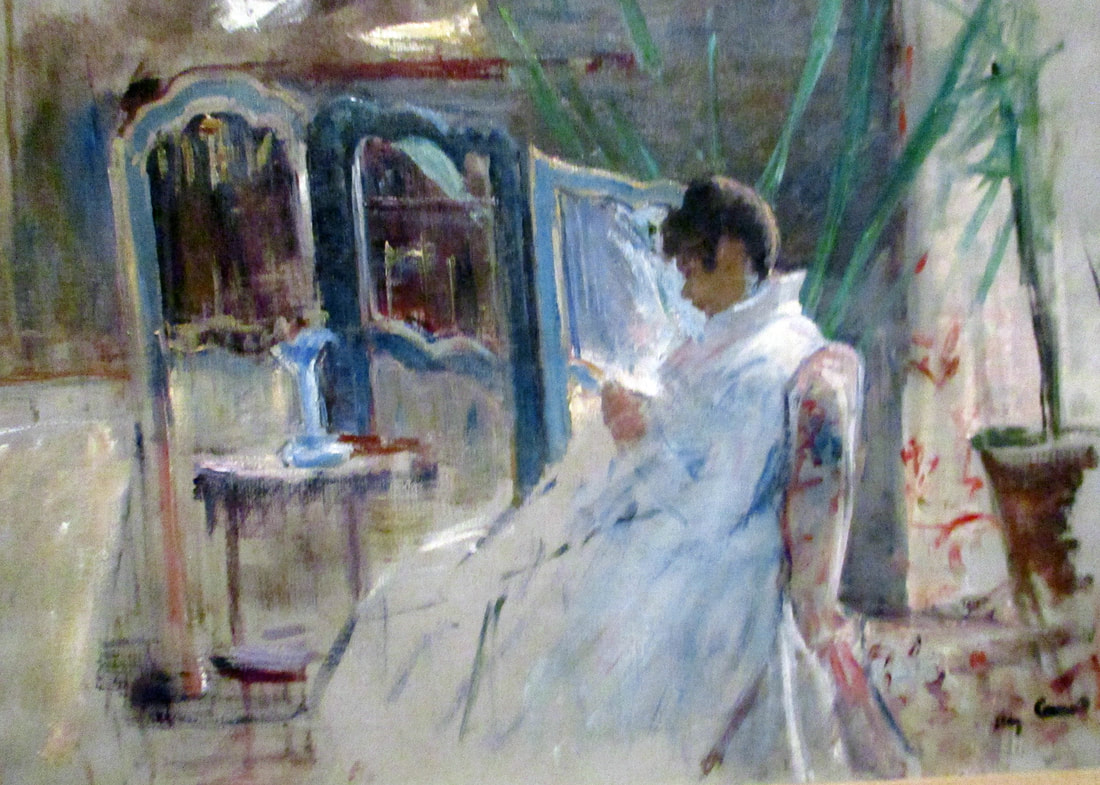

Below: "The Boating Party" reflects the influence of Japanese prints on Cassatt's work. Above: "Interior With French Screen". Like Degas, Cassatt viewed herself as primarily a figure painter.

Cassatt often depicted scenes of women of her class going about everyday activities.

Above: "The Tea." Below: Cassatt's mother posed for this painting of a woman reading the newspaper. Above: Cassatt is perhaps best known for her depictions of children and mothers with children.

See our profiles of these other Impressionists and members of their circle.

Frederic Bazille Eugene Boudin Marie Bracquemond Gustave Caillebotte Paul Cezanne Edgar Degas Henri Fantin-Latour Paul Gauguin Eva Gonzales Armand Guillaumin Edouard Manet Claude Monet (Part I The Early Years) Claude Monet (Part II High Impressionism) Claude Monet (Part III The Giverny Years) Berthe Morisot Camille Pissarro Pierre Auguste Renoir Alfred Sisley Suzanne Valadon Victor Vignon |

Artist appreciation - Mary Cassatt