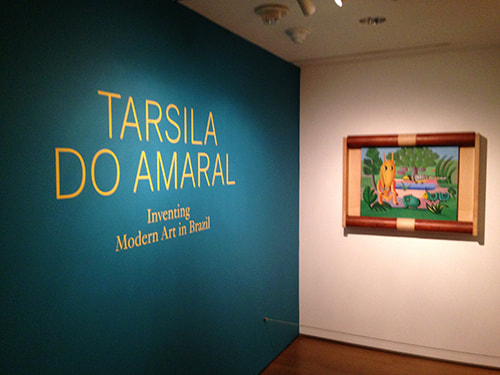

“Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a large exhibition that places in context much of the art created in France from the French Revolution to World War I. It explains why so much attention was paid by artists such as the Impressionists to the out doors as a subject. Extending from the late 18th century through the 19th century a passion developed in France for parks and gardens. Several factors came together to fuel this passion. First, as a result of the French Revolution, the parks and hunting reserves that had heretofore been open only to royalty and the aristocracy, became open to everyone. This access helped to open the eyes of the public to the beauties of nature. Second, the Industrial Revolution also changed the character of society. The middle class grew and people had more leisure time. They wanted green spaces, both public parks and private gardens, where they could escape from the stresses and pollution that were the less attractive side effects of industrialization. Accordingly, in the grand re-design of Paris that took place in the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann included tree-lined boulevards and some 30 parks and squares. Other cities and towns throughout France followed suit. Third, it was also a period of exploration and travel. Exotic plants were being brought back to France, stirring the public imagination. The Empress Josephine, first wife of Napoleon, and a celebrity in her day, spurred public interest in such plants by making her greenhouse at Malmaison a horticulture hub for exotic species. Artists were not immune from these forces. The natural world, depicted in landscapes and in still lifes, had long been a subject for art. However, a new enthusiaum developed. The painters of the Barbizon School took inspiration from the former royal hunting grounds at Fontainebleau. Later, the Impressionists, whose aims included depicting scenes of modern life, reflected public's passion for parks, gardens and the natural world in their works. While this exhibition includes earlier works, the Impressionists and the artists that they influenced dominate the exhibition. For example, in the gallery “Parks for the Public,” we see works by Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and others of former royal hunting reserves. However, you also have masterpieces by Calude Monet and Camille Pissaro of city parks in Paris. There is also a wonderful watercolor by Berthe Morrisot “A Woman Seated at a Bench on the Avenue du Bois” as well as a study by Pointillist George Seurat for “"A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." In the gallery “Private Gardens,” the works reflect the fact that people wanted to have their own green spaces where they could cultivate plants and escape from the outside world. Many artists were also amateur gardeners during this period. Of course, the dominant figure here is Claude Monet who was painting garden scenes long before he created his famous garden at Giverney. However, lesser known watercolors of garden scenes by Renoir and by Cezanne should not be overlooked. With regard to portraiture, we see that the artists blurred the distinction between portraits and genre painting. They are both depictions of individuals and scenes of everyday life. As a result, the identity of the sitter is no longer paramount if important at all to the success of the work. Furthermore, nature is an equal partner in these scenes, not just a background. To illustrate, Edouard Manet's “The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil” is a portrait of Monet and his family. The figures are arranged in a relaxed manner rather than in traditional portrait poses. Thus, it is also a scene of everyday life. Moreover, it would be just as successful if the figures were an unidentified family because it is a captivating garden scene. The passion for nature also brought about a revival of interest in floral still life painting. The exhibition presents examples by Manet, Monet, Cassat, Degas, and Matisse to name a few. But Vincent Van Goghs paintings of sunflowers and irises attract the most viewers. Given the popularity of the Impressionists and their broader circle, one would expect any exhibit in which they are prominent to be successful. However, the Met has done a good job here of supporting the theme of the exhibition. In addition to the paintings, there are drawings, prints contemporary photographs and objects relating to this theme. The signage is also good.  Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School of landscape painting are distinctly American, depicting the magnificent scenery of the United States in the first part of the 19th century. In “Thomas Cole's Journey Atlantic Crossings,” as exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we wee how both Cole's art and his thinking was shaped by his experiences in Europe. Cole was born in northwest England in 1801. The Industrial Revolution was beginning and during his boyhood, Cole witnessed the transformation from a rural society to an industrial one with nature giving way to factories and crowded cities. For a time, the young Cole worked in the new mills designing patterns for textiles. However, in 1818, facing financial hardship in England, Cole's father moved the family to the United States. As a young man Thomas Cole traveled around Pennsylvania and Ohio painting portraits. Although he was largely self-taught, Cole achieved some success, exhibiting his work at the Philadelphia Academy. In 1825, Cole fell in love, not with a person but with the beauty of the undeveloped Catskill region of New York. He painted what he saw and although landscape painting was not a well-established genre in the young United States, his paintings drew attention and he was made a member of the National Academy. Cole decided that in order to develop as an artist he had to return to Europe. There he could study past masters and meet leading contemporary artists. His first stop was England. There was a long tradition of landscape painting in England. In addition, two contemporary painters were taking this genre in new directions. J. M. W. Turner was incorporating bold colors and unrestrained brush work to produce pieces that were significantly different than traditional landscape painting. His work has been described as a forerunner of modern art. Cole was impressed with some of Turner's paintings but was uncomfortable with both Turner's unkempt appearance and the wildness of his approach to art. Cole was much more comfortable with John Constable, with whom he became friends. Constable's large finished canvases were more traditional and constrained than Turner's works. However, the oil sketches that he made in preparation for his finished works have a great freedom of brush work and spontaneity. In addition to Cole's work, the exhibit displays some of the works by Turner and Constable that Cole saw or could have seen during his journey. Particularly interesting are the numerous Constable oil sketches. Cole did not just stay in England but traveled into France and Italy. In Italy, he enrolled in classes. made copies of works by Renaissance masters and made oil sketches of the Italian countryside and Roman ruins. As he had hoped, Cole's journey to Europe enhanced his artistic skills. In addition, he met many wealthy Americans while traveling abroad and received a number of commissions. As a result, his reputation also grew. Returning to the U.S., Cole had a successful exhibition of his European paintings in New York City. More commissions followed. He established a studio in the Catskills. Other artists also came to study under Cole and he shaped an artistic movement. Having seen the results of unfettered industrialization in England, Cole became very concerned that President Andrew Jackson was leading the country in the wrong direction. The beautiful American wilderness was in danger from unrestrained development. Cole took up his brushes to warn of the consequences. Thus, while Cole's works may appear to be just paintings of beautiful scenes, they are actually political pictures. Cole was saying that all this will be lost if you continue with such policies. It is still a timely message. In this vein, the exhibit presents a series known as “The Course of Empire.” In the various canvases, Cole shows the same landscape first in its wild state and then progressively through development into a classical city and eventually to the final ruin of civilization. Perhaps more more subtlety, Cole expresses much the same message in“The Oxbow,” which shows a pristine river valley about to be engulfed by a massive storm. Cole's works transcend their political message. He had mastered traditional landscape painting and used it to portray magnificent scenes. Furthermore, his ability to compose a scene so as to make it speak to a wide audience cannot be denied.  "The Long Run” at New York's Museum of Modern Art is an exhibition encompassing works by nearly 50 artists who were active in modern art during the second half of the 20th century. The artists include numerous famous names such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichenstein, Andy Warhol and Georgia O'Keefe. The works exhibited are examples of work done later in these artists' careers. Rejecting the notion that innovation in art is “a singular event—a bolt of lightning that strikes once and forever changes what follows,” the exhibit seeks to show that “invention results from sustained critical thinking, persistent observation, and countless hours in the studio.” The exhibit seeks to illustrate its thesis by presenting works that show the evolution of the artists' works past the time when they were first recognized. One cannot seriously debate the exhibit's thesis. The notion of an artist being struck with a bolt from the blue that leads to a new direction in art is more the stuff of Hollywood drams than reality. As in other siciplines, artists develop their thoughts over time. Skills are refined and new materials are encountered that enable the artist to do new and/or different things, At the same time, personal relationships may be changing, new associations formed and events in the outside world may occur that influence the artist's thinking. Not only is there an evolutionary trail leading up to an artistic breakthrough but there is a trail after that breakthrough. The exhibit shows that artists evolve in different ways. Some artists make radical changes in style. For example, in 1969, Phillip Guston abandoned the abstract style that he had been known for in favor of a more figurative style. He said that he needed to make this change in order to enable him to address the political and social issues of the day. Other artists continue on in the same vein that first brought them recognition. For example, Andy Warhol's black and white drawing of Da Vinci's Last Supper with various colored consumer product logos superimposed makes essentially the same point as his earlier paintings of Campbell's Soup cans, i.e., the commercialization of western society. Along the same lines, Roy Lichenstein's “Interior with Mobile” is similar in style to his earlier comic strip inspired works. Even for those artists who stayed close to their original style, the exhibit makes the point that these artists went on working throughout their lives. In some cases, the later works may not have be as important to the history of art as their earlier works but these artists continued to produce vibrant and worthwhile art. Leaving aside the thesis of the exhibit, the Long Run is still an enjoyable exhibit. It brings together numerous examples of good modern art. This includes lesser known examples by major artists that deserve to be brought to the public's attention. “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” at the Museum of Modern Art presents the work of the artist who led the development of the modernist movement in Brazil. During the 1920s, Tarsila, as she is widely known in Brazil, developed a distinctive style that was truly Brazilian. MOMA has assembled over 100 works drawn from various collections including some of her landmark paintings to document this development.

Tarsila was born in Capivari, a small town near Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1886. Her family owned coffee plantations. Although it was unusual at that time for girls from affluent families to pursue higher education, Tarsilia was allowed to pursue her interest in art, both in Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain. Her instructors were conservative, academic artists. In 1920, after the end of her first marriage, Tarsila went to Paris in 1920 to study at the prestigious Academie Julian. Her studies were again in the academic tradition. Meanwhile, a modern art movement had taken root in Brazil. The landmark Semana de Arte Moderna was a festival that called for an end to academic art. Upon Tarsila's return to Brazil, she discovered modern art became a leader in this movement, one of the five artists and writers in the Grupo dos Cincos. In 1922, she returned to Paris and studied with several Cubist artists including Ferdinand Leger and Andre Lehote. However, she continued to think in terms of Brazil. She painted “A Negra,” an abstract portrait of an Afro-Brazilian woman. Returning to Brazil, she embarked upon a tour around the country. The drawings of the countryside and everyday life she made while on this journey served as inspiration for later paintings. Her traveling companion was the writer Oswald de Andrade wrote a manifesto “Pau-Brasil” calling for truly Brazilian culture. She married Andrade in 1926. Tarsila made another journey to Paris in 1928 where she came into contact with surrealist art. (It should be noted that Tarsila did not live like a starving artist in Paris. A renown beauty from a wealthy family, she lived a lavish lifestyle, mixing with famous personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals). That same year, she painted “Abaporu” (the man who eats human flesh) as a birthday present for her husband. He used the image for the cover of his “Manifesto of Anthropology,” which called upon artists to cannibalize European culture and other influences in order to create a distinctive Brazilian culture. The painting and the manifesto are considered landmarks in the development of Brazilian culture. Tarsila's family fortune was all but lost as a result of The New York Stock Exchange crash of 1929 and the following Depression. Her marriage to Andrade ended the following year. In 1931, Tarsila traveled to Moscow with her new boyfriend, a communist doctor. There she was influenced by Socialist Realism. Her subsequent work was primarily concerned with social issues. The exhibition at MOMA focuses on the decade beginning with her journey to Paris in 1920. It demonstrates how Tarsila's work evolved incorporating over time elements of Cubism, Brazilian folk art and Surrealism while retaining her own style. Although she was influenced by each of these schools, she did not become part of them. Hers is a distinctive style: flat two dimensional; populated with simplified, distorted figures and landscapes; often with geometric backgrounds. It is also clearly Brazilian, not only in the choice of subject matter but in the selection of colors. In short, it is what Andrade was calling for - - a synthesis of a number of influences producing a truly Brazilian art. The exhibit also includes some works after her trip to Russia. “The Workers” (1933) was one of the first paintings in Brazil dealing with social issues. It reflects the influence of Soviet painting both in subject matter and palette. Incorporation of this soulless style was not a happy addition to Tarsila's arsenal. The work does not have the life of her earlier works and the treatment of the subject matter is much like what numerous other artists were doing at the time. However, it does serve to spotlight how special her work was during the preceding decade.  “Power and Grace” at the Morgan Library and Museum is a small exhibition that beings together works on paper by three masters of the Flemish Baroque - - one of art's golden ages. Not only were these three artists contemporaries in Antwerp but they worked together. As seen in their drawings, this relationship clearly influenced their styles. Peter Paul Ruebens was the preeminent artist of his day. Born in Germany, his family moved to Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands when he was 10 and that city became his base for the rest of his life. The son of a lawyer, his first job at the age of 13 was as a page to a countess but his desire was to become an artist led him to leave this prestigious job. He spent eight years traveling in Italy and Spain studying art. When he returned to Antwerp in 1608, he quickly established himself as a successful artist and was appointed court painter to the archduke and archduchess who governed the Spanish Netherlands on behalf of Spain. In addition to his artistic talent, Rubens was a skilled diplomat. In this role, he traveled extensively in Europe. One such mission took him to England, where he was knighted by King Charles I. He also secured a commission to paint the ceiling of the Banqueting House in London. Thus, he combined diplomacy and art. Rubens developed a large studio. Time did not allow him to do all of the commissions that he received from various royal courts, prosperous merchants and the church. As a result, drawing was very important to him, not only in developing ideas but in order to show his numerous assistants and pupils how he wanted his works completed. Anthony Van Dyck was at one point Rubens' chief assistant. Indeed, the master referred to Van Dyck as the “best of my pupils.” The son or a prosperous silk merchant, Van Dyck was an established painter in his own right by the time he was 15. Like Rubens, Van Dyck went to Italy to study art. Later, probably using recommendations furnished by Rubens, Van Dyck traveled to England. There, he was knighted and became principal painter to Charles I. Commissions poured in from the English court for portraits. Indeed, our image of Engliand's aristocratic society just prior to the English Civil War comes largely from Van Dyck. To handle all of his commissions, Van Dyck maintained a studio of assistants. Following in Rubens' footsteps, Van Dyck used drawings to show his staff his visions. Van Dyck would do a sketch and then it was largely left to the assistant to enlarge it and turn it into a finished painting. How much involvement the master had with each work varied from commission to commission. Like Van Dyck, Jacob Jordaens was born in Antwerp to a prosperous merchant family. Unlike Van Dyck and Rubens, Jordaens did not go to Italy to study art. Indeed, throughout his life, he rarely left Antwerp. Jordeans was nonetheless very influenced by Rubens. At that time, Ruebens was Antwerp's leading artist. On occasion, Rubens would employ Jordeans to enlarge and complete works based upon Rubens' concepts. When Rubens died in 1540, Jordeans became Antwerp's leading painter. (Van Dyck by that time was living in England. Moreover, Van Dyck would die in 1641). The exhibit at the Morgan brings together approximately 30 works on paper from these three masters. Most of the works are from the Morgan's collection but there are some works loaned from other collections. Not surprisingly given the relationship between these three artists, there is a great deal of similarity of style. This is perhaps most evident in three studies of male nudes: Rubens' “Seated Male Youth”; Van Dyck's “Study for the Dead Christ”; and Jordeans' “Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind “ All are works on colored paper using black chalk heightened by white chalk. In each, the muscles are prominent and handled similarly. There are also examples of preparatory sketches depicting scenes with religious themes. These are interesting for the economy of line that the artists used. Jordeans is the only one who used color but then he began his career using watercolor to create designs for tapestries. All of these artists did portraits but of the three, portraiture is most associated with Van Dyck. Indeed, Van Dyck can be said to have been the primary influence on English portraiture for centuries after his death. The exhibit presents one of his portrait sketches. It is a preparatory sketch for a painting that he did of the wife of a fellow artist and her daughter. Van Dyck took great care and precision with regard to the woman's clothes and jewelry. However, the face again has an economy of line. There is no modeling. Instead, he uses lines to suggest the features and shadows. A second portrait highlights the similarity in styles of these artists. “Portrait of a Young Woman” was for centuries attributed to Rubens. However, in the 1980s, that attribution was questioned and now the expert view is that it is one of the few portraits by Jordeans. Certainly, the use of bold lines and contrast is more similar to Jordeans' works elsewhere in the exhibit; Rubens' works are somewhat more vague. In any case, it is one of the most engaging works in the exhibition. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed