|

Click here for our review of the art exhibition "Drawing in Tintoretto's Venice" at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City.

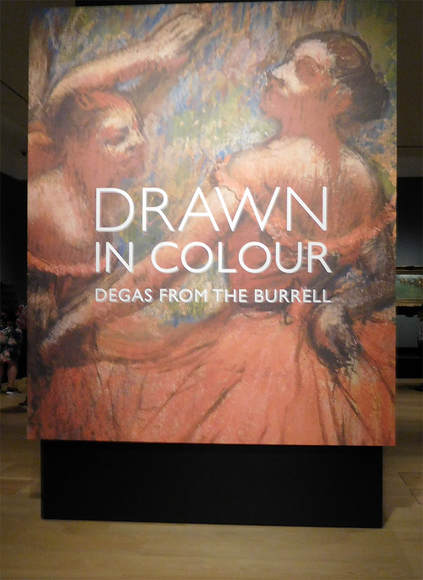

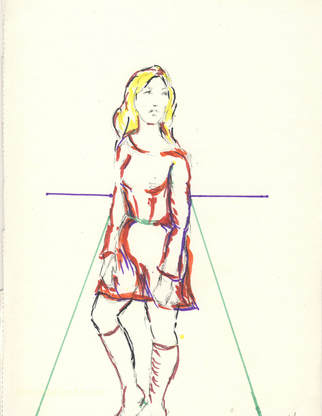

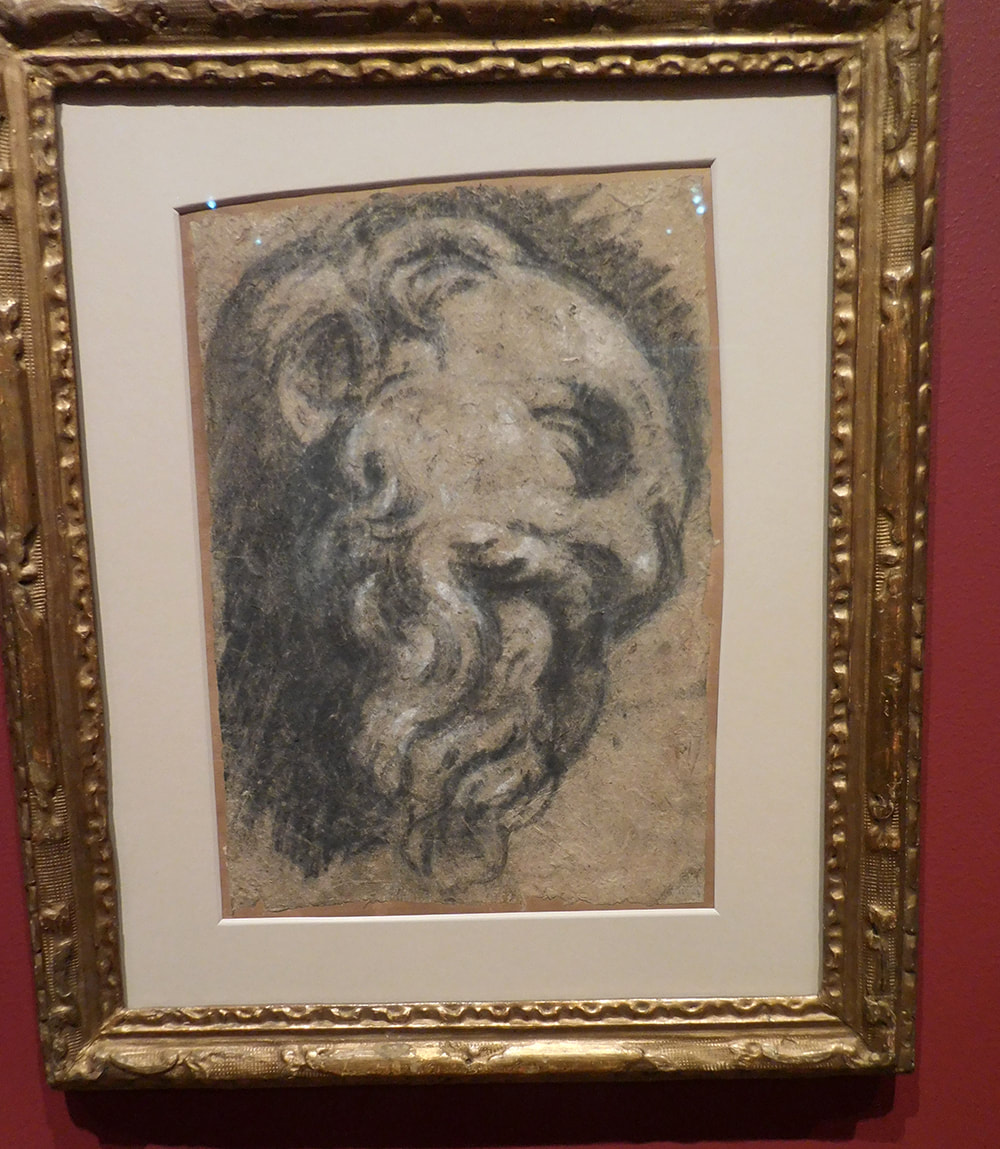

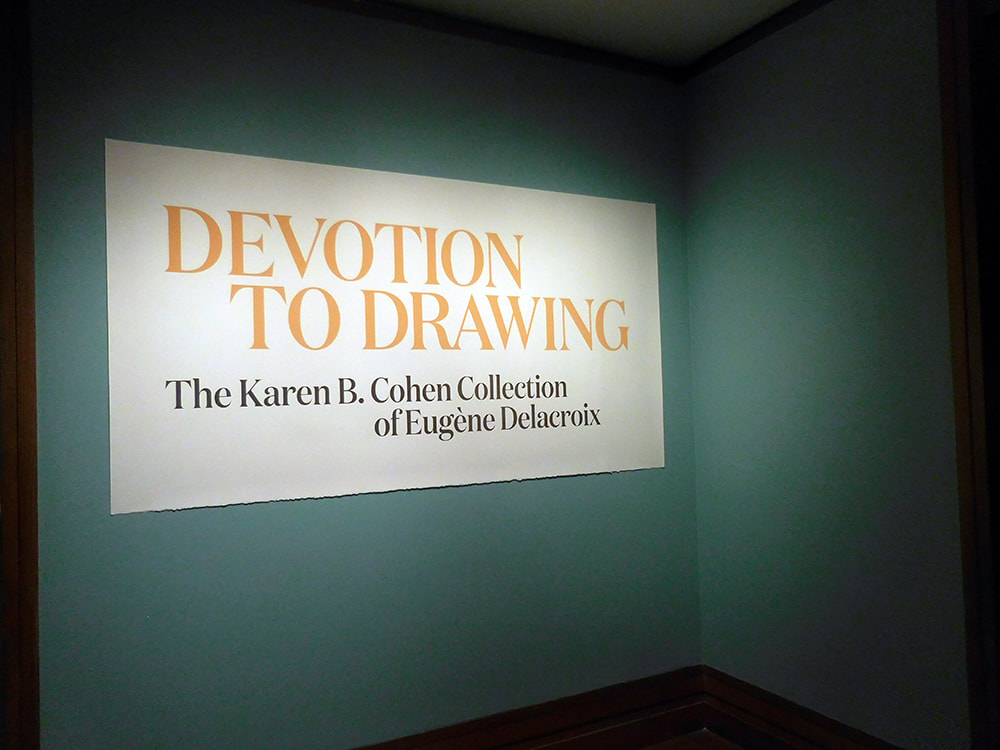

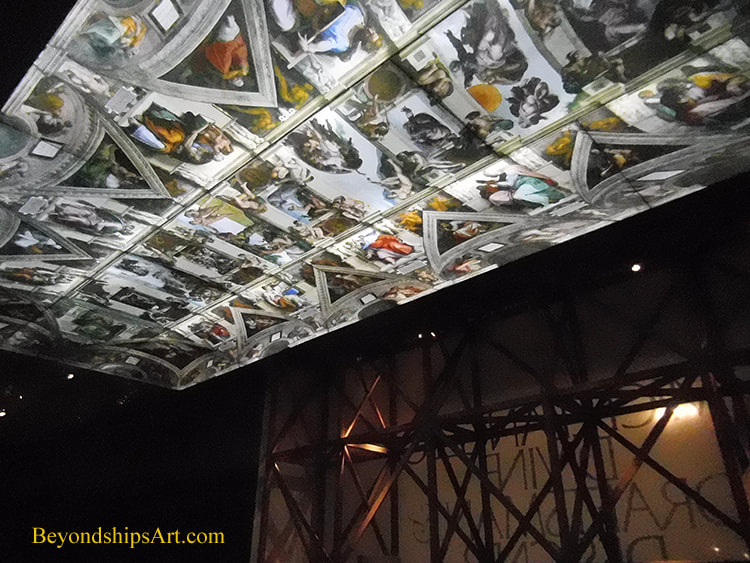

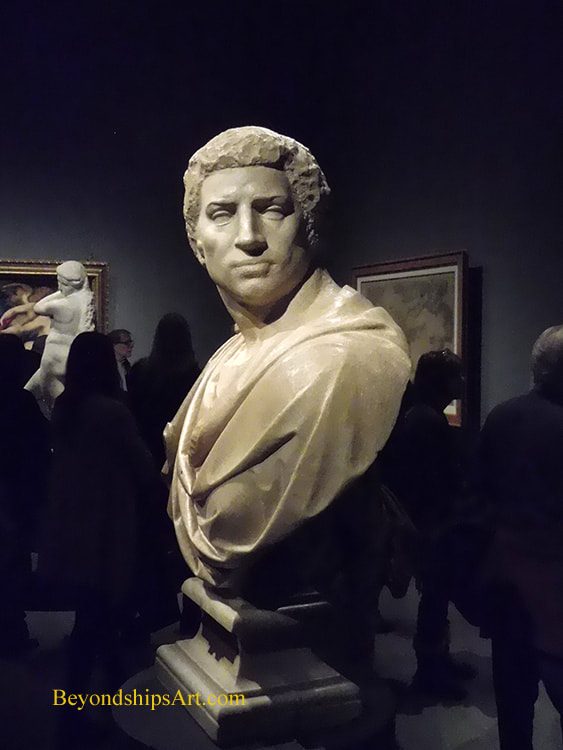

“Drawn In Colour: Degas From the Burrell” recat London's National Gallery brought together 20 works by Edgar Degas from Glasgow's Burrell Collection Gallery along with a number of works from the National Gallery's own collection. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born in Paris in 1834. His father was a French banker and his mother was from a New Orleans Creole family. His father was interested in the arts and encouraged Edgar's interest, often accompanying him to museums in Paris. Indeed, after Edgar made an unsuccessful attempt to fulfill his father's desire that he pursue a career in law, his father provided him with an art studio. Edgar's training in art was quite conventional. He studied at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts including drawing with Louis Lamothe, a disciple of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who Edgar greatly admired. He also traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. In both France and Italy, much of his time was spent copying masterpiece paintings and drawings. With this background, it is not surprising that Edgar's early work was influenced by conventional thinking about art. In those days, history painting was considered the highest form of fine art and so Edgar did history paintings. He also submitted and had works accepted by the Salon, the apex of the art establishment. Soon, however, Edgar's work became quite unconventional. Several factors contributed to this change. In 1864, he met Edouard Manet while he was copying a painting at the Louvre. They became good friends and Edgar came to share Manet's interest in depicting modern life. Following, the death of his father in 1873, Edgar sold off most of his assets in order to pay debts that had been amassed by his brother. As a result, Edgar, who was now spelling his last name “Degas”, had to rely on the sale of his art work to make his living. The primary factor in the evolution of Degas' work, however, was his quick mind. While he always retained his admiration for the great painters of the past, Degas was continually innovating. Diverse inspirations such as Japanese art and the new technology of photography influenced his compositions. He was interested in experimenting with different mediums, branching into photography, sculpture and, most particularly, pastels, which he applied in complex layers and textures. Although often conservative in his thinking on other matters, his thinking on art became quite radical. In 1874, he joined together with several other artists who were taking unconventional approaches to art for an exhibition. The group came to be known as the “Impressionists,” a label Degas hated. Degas helped organize the Impressionist exhibitions and exhibited in all but one of the Impressionist exhibitions. Degas added another dimension to Impressionism. Whereas his colleagues Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro mostly painted landscapes, Degas was interested primarily in the human figure. Whereas the other Impressionists preferred to work outdoors capturing what they were observing at the moment, Degas preferred to work in his studio, sometimes working from photographs or from memory. What connects Degas to the others, however, is an interest in depicting modern life, an interest in light and an interest in using color in unconventional ways. Because there were profound differences in the individual Impressionist's artistic philosophies and because the group included some difficult personalities (including Degas) the group eventually separated. There were only eight Impressionist exhibitions and after 1886, the artists went their separate ways. Degas, who was having problems with his eye-sight, became particularly solitary. Increasingly, he turned to pastels and sculpture. Again and again, he returned to certain subjects such as dancers, horse racing and women bathing. He died in 1917. Sir William Burrell (1861 - 1958) amassed 20 major works by Degas including works from every period of the artist's life. He donated these along with some 9,000 other works of art to the City of Glasgow in 1944. The closing of the Burrell Collection Gallery in Glasgow for renovation provided an opportunity for the Degas to be exhibited in London. The exhibition was presented in three sections: Modern Life; Dancers and Private Worlds - - in short three of Degas' signature subject matters. Although there were a few oil paintings and drawings, most of the works in the exhibition were pastels, Degas' favorite medium The presentation of these works together served to underscore how much of an innovator Degas was. His use of this medium was much different than conventional pastels. The strokes are vigorous conveying energy. The shapes verge on the abstract at times. The colors are often strong and bold.  “Power and Grace” at the Morgan Library and Museum is a small exhibition that beings together works on paper by three masters of the Flemish Baroque - - one of art's golden ages. Not only were these three artists contemporaries in Antwerp but they worked together. As seen in their drawings, this relationship clearly influenced their styles. Peter Paul Ruebens was the preeminent artist of his day. Born in Germany, his family moved to Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands when he was 10 and that city became his base for the rest of his life. The son of a lawyer, his first job at the age of 13 was as a page to a countess but his desire was to become an artist led him to leave this prestigious job. He spent eight years traveling in Italy and Spain studying art. When he returned to Antwerp in 1608, he quickly established himself as a successful artist and was appointed court painter to the archduke and archduchess who governed the Spanish Netherlands on behalf of Spain. In addition to his artistic talent, Rubens was a skilled diplomat. In this role, he traveled extensively in Europe. One such mission took him to England, where he was knighted by King Charles I. He also secured a commission to paint the ceiling of the Banqueting House in London. Thus, he combined diplomacy and art. Rubens developed a large studio. Time did not allow him to do all of the commissions that he received from various royal courts, prosperous merchants and the church. As a result, drawing was very important to him, not only in developing ideas but in order to show his numerous assistants and pupils how he wanted his works completed. Anthony Van Dyck was at one point Rubens' chief assistant. Indeed, the master referred to Van Dyck as the “best of my pupils.” The son or a prosperous silk merchant, Van Dyck was an established painter in his own right by the time he was 15. Like Rubens, Van Dyck went to Italy to study art. Later, probably using recommendations furnished by Rubens, Van Dyck traveled to England. There, he was knighted and became principal painter to Charles I. Commissions poured in from the English court for portraits. Indeed, our image of Engliand's aristocratic society just prior to the English Civil War comes largely from Van Dyck. To handle all of his commissions, Van Dyck maintained a studio of assistants. Following in Rubens' footsteps, Van Dyck used drawings to show his staff his visions. Van Dyck would do a sketch and then it was largely left to the assistant to enlarge it and turn it into a finished painting. How much involvement the master had with each work varied from commission to commission. Like Van Dyck, Jacob Jordaens was born in Antwerp to a prosperous merchant family. Unlike Van Dyck and Rubens, Jordaens did not go to Italy to study art. Indeed, throughout his life, he rarely left Antwerp. Jordeans was nonetheless very influenced by Rubens. At that time, Ruebens was Antwerp's leading artist. On occasion, Rubens would employ Jordeans to enlarge and complete works based upon Rubens' concepts. When Rubens died in 1540, Jordeans became Antwerp's leading painter. (Van Dyck by that time was living in England. Moreover, Van Dyck would die in 1641). The exhibit at the Morgan brings together approximately 30 works on paper from these three masters. Most of the works are from the Morgan's collection but there are some works loaned from other collections. Not surprisingly given the relationship between these three artists, there is a great deal of similarity of style. This is perhaps most evident in three studies of male nudes: Rubens' “Seated Male Youth”; Van Dyck's “Study for the Dead Christ”; and Jordeans' “Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind “ All are works on colored paper using black chalk heightened by white chalk. In each, the muscles are prominent and handled similarly. There are also examples of preparatory sketches depicting scenes with religious themes. These are interesting for the economy of line that the artists used. Jordeans is the only one who used color but then he began his career using watercolor to create designs for tapestries. All of these artists did portraits but of the three, portraiture is most associated with Van Dyck. Indeed, Van Dyck can be said to have been the primary influence on English portraiture for centuries after his death. The exhibit presents one of his portrait sketches. It is a preparatory sketch for a painting that he did of the wife of a fellow artist and her daughter. Van Dyck took great care and precision with regard to the woman's clothes and jewelry. However, the face again has an economy of line. There is no modeling. Instead, he uses lines to suggest the features and shadows. A second portrait highlights the similarity in styles of these artists. “Portrait of a Young Woman” was for centuries attributed to Rubens. However, in the 1980s, that attribution was questioned and now the expert view is that it is one of the few portraits by Jordeans. Certainly, the use of bold lines and contrast is more similar to Jordeans' works elsewhere in the exhibit; Rubens' works are somewhat more vague. In any case, it is one of the most engaging works in the exhibition.  “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art presents some 200 works by Michelangelo and his contemporaries. It includes 133 of Michelangelo's drawing as well as three of his marble sculptures gathered from 48 museums and private collections. It is a monumental exhibit. Although Michelangelo considered himself to be primarily a sculptor in marble, he was also a painter and an architect. In this exhibition, we see that the foundation of his art in all of these disciplines was drawing. But more than mere draftsmanship, his drawing reflected a quality of design. The exhibition uses the Italian word disego to capture this concept. Very few of the works in this exhibition were meant for public display. Rather, they were preparatory drawings made in order to work out ideas that would be used in paintings or sculptures. Others served to illustrate ideas for buildings. Because they were made further back in the creative process, they reveal something of how Michelangelo developed his ideas. To illustrate how some of the drawings led to finished works, the exhibit has a one quarter size reproduction of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel displayed ion the ceiling of one of the galleries. Visitors can look up from Michelangelo's drawing and see how that idea was used in the final masterpiece. The exhibit also places the drawings in context. For example, the exhibit is open about Michelangelo's love of young men and explains that his “divine heads” were drawings that he did of those men and as presents for them. It also discusses his platonic relationship with the poet Vittoria Colonna and presents the drawings that he did when he came under her influence. It also looks at his relationship with other artists. To illustrate, Raphael began to achieve success in Rome at a time when Michelangelo was living in Florence. In order to compete with Raphael, Michelangelo fed ideas to the painter Sebastiano. Michelngelo's powerful marble bust of Brutus is presented along with a Roman statue that inspired Michelangelo and a bust of Julius Caesar made by a contemporary of Michelangelo. This allows us to see the debt that Michelangelo owed to the ancients as well as how his work broke with what was fashionable when Michelangelo created his Brutus. Michelangelo is one of the best known artists of all time. Yet, this exhibit sheds light on his creative process and career that may not have been generally appreciated before.  Several people have asked me to explain what I mean by “essential line drawing” as used on this website and in various postings that I have made on social media. Essential line drawing is a term that I use to describe a type of drawing that I have been doing for many years now. I doubt that it is in any art dictionary but it is a handy way of describing this type of drawing. Distilled to its essence, essential line drawing seeks to produce an image with the minimum number of lines that are needed to convey the concept that the artist is trying to express. For example, in a portrait, the image would be the minimum number of lines needed to convey the essence of the sitter. In a scene, it could be to the lines needed to express the emotions of the moment. This is not meant to be an academic exercise. The objectives are simplicity and clarity. You are putting aside what is non-essential in order to allow that is essential to show through more clearly. There are examples of essential line drawing in the works of many famous artists. Papblo Picasso and Henri Matisse did essential line drawings. More recently, you can find examples in the works of Peter Max. Each of these artists had their own approach but the basic concept is the same. The end result often sits on the border between realism and abstraction. You can tell what the image is but it is far from being a photographic image. From a techncal perspective, the biggest difficulty often is doing too much. If you put in too many lines, it becomes a standard line drawing. More importantly, they obscure the concept. Again, the objectives are simplicity and clarity. This is not to say that the essential line approach is the only way to produce art. It is simply one approach that I use. There are examples of essential line portraits and essential line figure drawings on Beyondships Art.  In my view, this exhibition is mislabeled. The title “Gilded Age Drawings at the Met” suggests a collection of black and white sketches of hefty figures supposed to be gods and goddesses from Greek mythology or other syrupy themes that were popular in the late Victorian age. In reality, this exhibit is a delightful small group of colorful watercolors and pastels done by artists whose work has transcended their time. Included in this exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art are several watercolors by John Singer Sargent. Sargent was one of the most successful portrait painters of his day. However, he also did watercolors. These were not intended for public display but rather were for his own benefit. As a result, they are done in a very loose style using a palette reflecting the fact that he also spent time working with Monet and the Impressionism. Most of the Sargent watercolors are landscapes or other Impressionistic scenes. However, there is also a small watercolor done during World War I when he visited the front lines as a war artist. It is of two men suffering from the effects of mustard gas and is a very powerful piece. Thomas Eakins is also represented. Unlike Sargent, Eakins exhibited his watercolors and they bear a close resemblance to the style he used in his oil paintings. These are illustration-like scenes from everyday life including the controversial “Dancing Lesson.” Is it a sympathetic illustration of black life shortly after emancipation or is it meant as a comedy that re-enforces racial stereotypes? The signage appears to conclude the former noting that it won a silver medal when it was exhibited in Boston in the 1870s. There are also several watercolors by Winslow Homer. These capture the various moods and energy of the sea in a variety of scenes. Homer manipulated the watercolors to produce amazing sea and sky effects. James McNeill Whistler was also a successful Victorian era artist. However, his style looked more toward the future than the art establishment of the day. “His Lady in Grey” is a tiny watercolor that is similar in concept to some his full-length female portraits. I sometimes come across comments on social media about whether a watercolor should be just translucent paint. However, in almost all of these works, the masters used gouache (opaque watercolor) along with the translucent watercolors. Not all the works in this exhibit are watercolors. There are also two pastels by Mary Cassat. One is a large, yet tender, finished work that returns to her favorite theme - - the relationship between a mother and her child. The other work is more of a sketch on colored paper showing a woman on a bench knitting. There is a great deal of energy in the Impressionist master's short, seemingly rapid, strokes. There are also works by artists who are less well-known to the general public. Jane Peterson's scene of a New York City street during the patriotic parades around World War I complements Childe Hassan's popular paintings of those days. Charles Ethan Porter, an African American artists who specialized in still lifes is also represented. John LaFarge did not try to capture the image of flowers with absolute realism but rather sought to capture their essence thus foreshadowing the century which followed. Also on display are some artist boxes from the late 19th century. What is surprising is that the pans and tubes of watercolor paint and the brushes do not look much different than those of today.  Major exhibitions of drawings seem to be proliferating. In recent weeks, I have reviewed such exhibits at the Morgan Library and Museum, the National Portrait Gallery in London and now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This attention is well-deserved because as the Met correctly says “drawing is the foundation of all the visual arts.” “Leonardo to Matisse” is a survey of European art from the Renaissance to the 20th century. It is done through works from such masters as Leonardo, Rembrandt, Duerer, Tiepolo, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Matisse. Moreover, because it is done utilizing works from the collection of one person, viewing the exhibit is a conversation with one connoisseur about art. The works on exhibit are from the Met's Robert Lehman Collection. Robert Lehman graduated from Yale University in 1913 and by 1925 he was the head of the family-business, the investment banking house Lehman Brothers. He expanded that firm, bringing in outside partners, and made it into a financial powerhouse. Mr. Lehman's interest in art began at an early age. His father and mother collected art and by the time Robert was a teenager, he had begun collecting on his own. Over the years, he accumulated a massive collection focusing on European Art from the 14th to the 20th century. By 1962, it had become so massive that he used the townhouse that he grew up on New York's West 54th Street solely as a repository for his collection. It was not just a large collection but an important collection. Parts of it had been exhibited by the Louvre in Paris, the first private American collection to be so honored. Lehman took advice from experts in making his purchases but he also simply purchased what he liked. Following Lehman's death in 1969, the Robert Lehman Foundation bestowed the collection of some, 2,600 works to the Metropolitan, where Mr. Lehman had been a trustee and chairman of the board. A new wing was constructed to exhibit the collection in order to follow his stipulation that the works be exhibited together as a collection. There were more than 750 drawings in the collection. This exhibit presents some 60 works, which the Met describes as presenting “the full range of Robert Lehman's vast and distinguished drawings collection.” We can see from this exhibit that Mr. Lehman was interested in a broad span of European art. Although the signage tells us that his first interest was in Italian Renaissance drawing, the works include sheets from other times, other parts of Europe and a wide range of styles. Indeed, the works extend up to Modernism and Neo-Impressionism. Some of the works were acquired directly from living artists. Lehman also preferred finished drawings. This is not to say that all these works were finished in the sense that they were meant for public display. To the contrary, many were clearly done for the artist's own benefit in preparation for a painting or sculpture or to work out some problem of proportion or lighting etc. Indeed, Durer's self-portrait is on a sheet with a large study of a hand and Degas' dancer has other drawings on the reverse side. Rather, they are finished in the sense that the artist completed the concept. Few of the works are hasty sketches. Most of the drawings are relatively small. Consequently, they require close viewing which in turn creates an intimacy with the work. A collector would not have purchased these to decorate a large room but rather to examine from time-to-time. Very few of the drawings have color. Most are drawings done in black, brown or sometimes a combination of black, white and red chalk. Only one, a delightful tiny watercolor by Renoir, makes use of vibrant color. The exhibit is on the lower floor of the Robert Lehman Wing. Many of the paintings that Lehman collected are on display on the upper floor. While the drawings are excellent, they are overshadowed by the paintings, which include masterpieces by Ingres, Goya and Raeburn and the Impressionist masters Monet, Pissaro and Renoir.  The Encounter, Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, at the National Portrait Gallery in London, is the NPG's first exhibition of Renaissance portrait drawings. It includes 48 works by artists of the highest caliber and includes works from some of the most important collections in the United Kingdom including the Royal Collection. Just bringing together works by the likes of Leonardo Da Vinci, Rembrandt Van Rijn, Hans Holbien the Younger, Anthony Van Dyck and Albrecht Durer is enough to make an exhibit important. However, the NPG has striven to go beyond just creating an assembly of works by great artists by selecting works that highlight the interaction between the artist and his subject. Every portrait drawing involves the artist who renders the image and the subject, i.e., the one whose image is being rendered. Usually, this involves at least two people but in the case of a self-portrait, there is only one person involved. In such instances, the artist plays both roles. In this encounter, the subject provides not just his or her physical form but also the emotions and thoughts that animate that form. The artist not only recreates the image before him or her but interprets the subject in light of his or her thoughts and emotions. It is this interaction that makes art different than the process of copying a document on a copier. During the Renaissance, artists made their living primarily through painting. Drawings were usually not done as finished works. Often they were done as preparatory works where the artist was trying to develop an image that would later be used in a finished work, perhaps as a commissioned portrait painting or as a face in a mural of some Biblical scene. Indeed, in one of the Holbeins, the artist scribbled notes as to the subject's complexion and the fabric of the clothing the subject was wearing so as to guide him in the final painted portrait. Drawings were also done for practice. The very informative pamphlet distributed by the NPG explains that young artists would often learn their craft by copying collections of images done by their master. Practice continued even when an artist became established as seen in a sheet of drawings by Rembrandt that contains multiple quickly sketched images. Because these works were done primarily for the artist's own use, they are often freerer than the same artist's more polished finished paintings. The subjects are often more informal and appear in their own attire rather than say in classical costume. As such, the encounter - - the interaction between artist and subject - - is closer to the surface and more easily observed. Pictures from the Exhibition: A sheet of figure studies with male heads and three sketches of a woman with child by Rembrandt van Rijn c.1636 (above left).

Young Woman in a French Hood, Possibly Mary Zouch, by Hans Holbien the Younger c. 1653. (Images courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery).  Drawn to Greatness, Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection is the largest collection of drawings yet to be exhibited at the Morgan Library and Museum and includes some 150 works. However, beyond the quantity of works, this exhibit is important because of the quality of the works. The artists represented in the exhibit are a Who's Who of western art from the Renaissance to the 20th century. Consequently, works of beauty and excellence unfold as you walk through the galleries. The exhibit is drawn from the Thaw Collection, a gift of some 400 sheets by Eugene and Clare Thaw. It was amassed over the last 50 years by Mr. Thaw, an art dealer and collector. Interestingly, Mr. Thaw began his career handling the works of contemporary artists only later expanding into Old Masters. Mrs. Thaw encouraged her husband to keep some of the drawings that he was particularly enthusiastic about and so the collection was born. Works from the Renaissance are the earliest works in the exhibit. As the signage at the exhibit tells us, this was when artistic drawing changed from mechanically recording an image to intellectually creating an image. The exhibit then proceeds chronologically through the centuries, revealing the many ways artists used drawing to create images. The term drawing is used here in its broadest sense. It does not just encompass black and white images done with graphite or charcoal. Rather, the exhibit shows that there are many forms of drawing often involving color. These include pastels, watercolor, inks, chalks, and even oil paint to name a few mediums. Indeed, I was struck by how artists in the 18th century would use several different mediums in their works. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line, this multi-medium practice became lost so that today on social media an artist can be accused of “cheating” if a work contains say both gouache and watercolor. The works here include finished pieces as well as works done in preparation for a painting or mural. However, because the drawings were often for the artist's personal use they are sometimes more revealing than works produced for sale as they are not as tempered by the need to please the tastes of the market. Turner's “The Pass of St. Goddard,” for example, is a swirling mass of colors that is closer to abstraction than realism. Still, the drawings bear the hallmarks of the style which is associated with each artist. To illustrate, an Ingres' drawing looks like an Ingres portrait. You do not need to look at the signage to tell if a drawing was done by Picasso. As a result, the exhibit is a condensed survey of the major ideas in European art. I found myself spending the most time with the late 19th century French masters. Degas is known for his pastels and so it was not surprising to find several of them on exhibit. But there was also a rare black and white drawing by Monet, the master of color. There are also delightful watercolors by Renoir and Morisot. The innovative works by Cezanne take watercolor in a different direction. In addition to being an important exhibition for art lovers, I would also recommend this exhibit to those who make art. It is perhaps easier to push back the curtain and analyze how a work was done with a drawing as opposed to a finished painting. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed