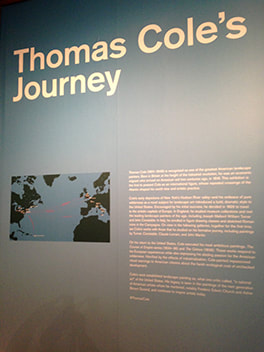

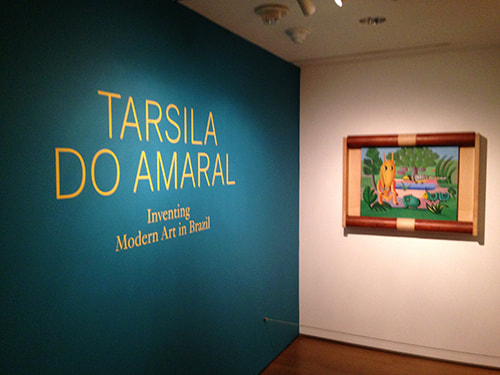

"Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddist Painting” at the Asia Society Museum in New York City presents a selection of Tibetan paintings collected during the expeditions of Giuseppe Tucci during his expeditions to Tibet along with some of the photographs that were taken during the expedition. The paintings in the exhibit are from the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci," in Rome and are being shown for the first time in the United States. Giuseppe Tucci was a writer, scholar and explorer who made eight expeditions to Tibet during the period 1926 to 1948. Up to that time, Tibet was a remote mystery and Tibetan culture largely unknown outside of Tibet. Tucci traveled some 5,000 miles on foot and on horseback across the Tibetan plateau, In addition to meeting people and seeing places, he obtained permission to collect examples of Tibetan culture for study outside the country. In addition, Tucci brought along photographers to document the expeditions. Their mission included photographing monuments, cultural artifacts, people and their occupations. In other words, they made a systematic effort to document this ancient culture before it vanished. The exhibition presents copies of some of the 14,000 photographs that were taken. Done in black and white, with strong contrast, the images are artistic in themselves. They reveal a treeless, stark world populated by people who are both rugged and spiritual. The core of the exhibition, however, is the paintings. Done on fabric, the majority of these paintings are religious paintings designed to be an aid in meditation and ritual. Most relate to Buddhism but some relate to earlier religions. Deemed to be in too poor condition to be used in religious practice, Tucci acquired paintings by purchase and by gift. A number of the paintings were discovered in a cave by one of his photographers. The ones on exhibit have now been restored. The paintings are full of religious symbols and meaning. Indeed, even the 17th century Arhat paintings, which look at first glance like a series of portraits, have symbolic meaning. The Arhats were disciples of the Shakyamuni Buddha. In each of the paintings, there is a dominant central figure. Around him are various figures and animals, each of which relates to some aspect of the central figure's life. Furthermore, the paintings relate to each other as they were to be hung in a certain order in the temple. Leaving aside their religious meaning, the paintings work as art. The figures are done delicately with relatively few lines, avoiding unnecesary detail. Beyond the figures are serene landscapes Flat and two dimensional, the images also have an abstract appeal. The restored colors are bright and appealing.  Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School of landscape painting are distinctly American, depicting the magnificent scenery of the United States in the first part of the 19th century. In “Thomas Cole's Journey Atlantic Crossings,” as exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, we wee how both Cole's art and his thinking was shaped by his experiences in Europe. Cole was born in northwest England in 1801. The Industrial Revolution was beginning and during his boyhood, Cole witnessed the transformation from a rural society to an industrial one with nature giving way to factories and crowded cities. For a time, the young Cole worked in the new mills designing patterns for textiles. However, in 1818, facing financial hardship in England, Cole's father moved the family to the United States. As a young man Thomas Cole traveled around Pennsylvania and Ohio painting portraits. Although he was largely self-taught, Cole achieved some success, exhibiting his work at the Philadelphia Academy. In 1825, Cole fell in love, not with a person but with the beauty of the undeveloped Catskill region of New York. He painted what he saw and although landscape painting was not a well-established genre in the young United States, his paintings drew attention and he was made a member of the National Academy. Cole decided that in order to develop as an artist he had to return to Europe. There he could study past masters and meet leading contemporary artists. His first stop was England. There was a long tradition of landscape painting in England. In addition, two contemporary painters were taking this genre in new directions. J. M. W. Turner was incorporating bold colors and unrestrained brush work to produce pieces that were significantly different than traditional landscape painting. His work has been described as a forerunner of modern art. Cole was impressed with some of Turner's paintings but was uncomfortable with both Turner's unkempt appearance and the wildness of his approach to art. Cole was much more comfortable with John Constable, with whom he became friends. Constable's large finished canvases were more traditional and constrained than Turner's works. However, the oil sketches that he made in preparation for his finished works have a great freedom of brush work and spontaneity. In addition to Cole's work, the exhibit displays some of the works by Turner and Constable that Cole saw or could have seen during his journey. Particularly interesting are the numerous Constable oil sketches. Cole did not just stay in England but traveled into France and Italy. In Italy, he enrolled in classes. made copies of works by Renaissance masters and made oil sketches of the Italian countryside and Roman ruins. As he had hoped, Cole's journey to Europe enhanced his artistic skills. In addition, he met many wealthy Americans while traveling abroad and received a number of commissions. As a result, his reputation also grew. Returning to the U.S., Cole had a successful exhibition of his European paintings in New York City. More commissions followed. He established a studio in the Catskills. Other artists also came to study under Cole and he shaped an artistic movement. Having seen the results of unfettered industrialization in England, Cole became very concerned that President Andrew Jackson was leading the country in the wrong direction. The beautiful American wilderness was in danger from unrestrained development. Cole took up his brushes to warn of the consequences. Thus, while Cole's works may appear to be just paintings of beautiful scenes, they are actually political pictures. Cole was saying that all this will be lost if you continue with such policies. It is still a timely message. In this vein, the exhibit presents a series known as “The Course of Empire.” In the various canvases, Cole shows the same landscape first in its wild state and then progressively through development into a classical city and eventually to the final ruin of civilization. Perhaps more more subtlety, Cole expresses much the same message in“The Oxbow,” which shows a pristine river valley about to be engulfed by a massive storm. Cole's works transcend their political message. He had mastered traditional landscape painting and used it to portray magnificent scenes. Furthermore, his ability to compose a scene so as to make it speak to a wide audience cannot be denied. “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” at the Museum of Modern Art presents the work of the artist who led the development of the modernist movement in Brazil. During the 1920s, Tarsila, as she is widely known in Brazil, developed a distinctive style that was truly Brazilian. MOMA has assembled over 100 works drawn from various collections including some of her landmark paintings to document this development.

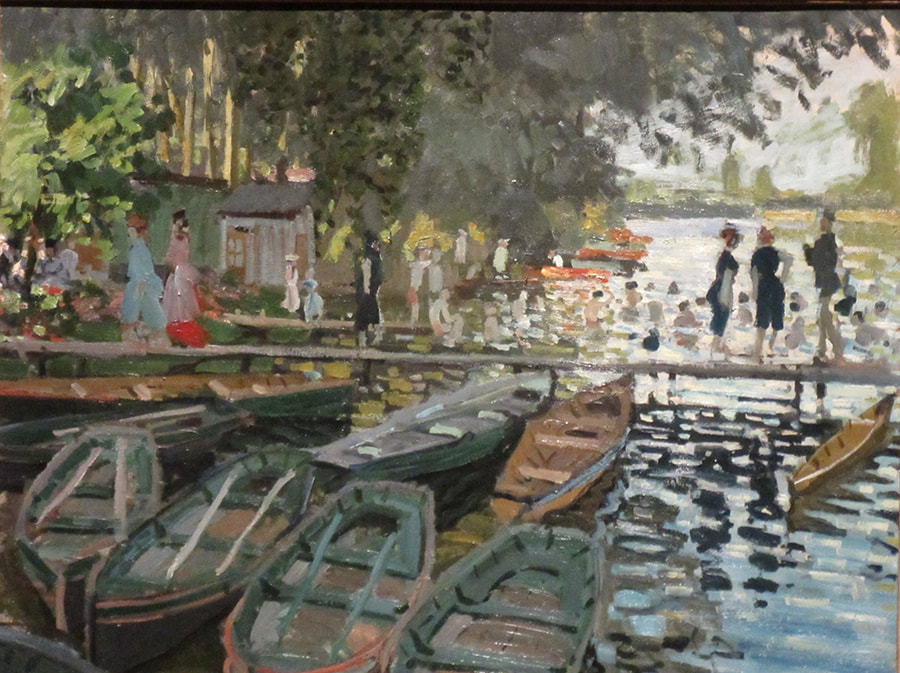

Tarsila was born in Capivari, a small town near Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1886. Her family owned coffee plantations. Although it was unusual at that time for girls from affluent families to pursue higher education, Tarsilia was allowed to pursue her interest in art, both in Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain. Her instructors were conservative, academic artists. In 1920, after the end of her first marriage, Tarsila went to Paris in 1920 to study at the prestigious Academie Julian. Her studies were again in the academic tradition. Meanwhile, a modern art movement had taken root in Brazil. The landmark Semana de Arte Moderna was a festival that called for an end to academic art. Upon Tarsila's return to Brazil, she discovered modern art became a leader in this movement, one of the five artists and writers in the Grupo dos Cincos. In 1922, she returned to Paris and studied with several Cubist artists including Ferdinand Leger and Andre Lehote. However, she continued to think in terms of Brazil. She painted “A Negra,” an abstract portrait of an Afro-Brazilian woman. Returning to Brazil, she embarked upon a tour around the country. The drawings of the countryside and everyday life she made while on this journey served as inspiration for later paintings. Her traveling companion was the writer Oswald de Andrade wrote a manifesto “Pau-Brasil” calling for truly Brazilian culture. She married Andrade in 1926. Tarsila made another journey to Paris in 1928 where she came into contact with surrealist art. (It should be noted that Tarsila did not live like a starving artist in Paris. A renown beauty from a wealthy family, she lived a lavish lifestyle, mixing with famous personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals). That same year, she painted “Abaporu” (the man who eats human flesh) as a birthday present for her husband. He used the image for the cover of his “Manifesto of Anthropology,” which called upon artists to cannibalize European culture and other influences in order to create a distinctive Brazilian culture. The painting and the manifesto are considered landmarks in the development of Brazilian culture. Tarsila's family fortune was all but lost as a result of The New York Stock Exchange crash of 1929 and the following Depression. Her marriage to Andrade ended the following year. In 1931, Tarsila traveled to Moscow with her new boyfriend, a communist doctor. There she was influenced by Socialist Realism. Her subsequent work was primarily concerned with social issues. The exhibition at MOMA focuses on the decade beginning with her journey to Paris in 1920. It demonstrates how Tarsila's work evolved incorporating over time elements of Cubism, Brazilian folk art and Surrealism while retaining her own style. Although she was influenced by each of these schools, she did not become part of them. Hers is a distinctive style: flat two dimensional; populated with simplified, distorted figures and landscapes; often with geometric backgrounds. It is also clearly Brazilian, not only in the choice of subject matter but in the selection of colors. In short, it is what Andrade was calling for - - a synthesis of a number of influences producing a truly Brazilian art. The exhibit also includes some works after her trip to Russia. “The Workers” (1933) was one of the first paintings in Brazil dealing with social issues. It reflects the influence of Soviet painting both in subject matter and palette. Incorporation of this soulless style was not a happy addition to Tarsila's arsenal. The work does not have the life of her earlier works and the treatment of the subject matter is much like what numerous other artists were doing at the time. However, it does serve to spotlight how special her work was during the preceding decade.  “Power and Grace” at the Morgan Library and Museum is a small exhibition that beings together works on paper by three masters of the Flemish Baroque - - one of art's golden ages. Not only were these three artists contemporaries in Antwerp but they worked together. As seen in their drawings, this relationship clearly influenced their styles. Peter Paul Ruebens was the preeminent artist of his day. Born in Germany, his family moved to Antwerp in the Spanish Netherlands when he was 10 and that city became his base for the rest of his life. The son of a lawyer, his first job at the age of 13 was as a page to a countess but his desire was to become an artist led him to leave this prestigious job. He spent eight years traveling in Italy and Spain studying art. When he returned to Antwerp in 1608, he quickly established himself as a successful artist and was appointed court painter to the archduke and archduchess who governed the Spanish Netherlands on behalf of Spain. In addition to his artistic talent, Rubens was a skilled diplomat. In this role, he traveled extensively in Europe. One such mission took him to England, where he was knighted by King Charles I. He also secured a commission to paint the ceiling of the Banqueting House in London. Thus, he combined diplomacy and art. Rubens developed a large studio. Time did not allow him to do all of the commissions that he received from various royal courts, prosperous merchants and the church. As a result, drawing was very important to him, not only in developing ideas but in order to show his numerous assistants and pupils how he wanted his works completed. Anthony Van Dyck was at one point Rubens' chief assistant. Indeed, the master referred to Van Dyck as the “best of my pupils.” The son or a prosperous silk merchant, Van Dyck was an established painter in his own right by the time he was 15. Like Rubens, Van Dyck went to Italy to study art. Later, probably using recommendations furnished by Rubens, Van Dyck traveled to England. There, he was knighted and became principal painter to Charles I. Commissions poured in from the English court for portraits. Indeed, our image of Engliand's aristocratic society just prior to the English Civil War comes largely from Van Dyck. To handle all of his commissions, Van Dyck maintained a studio of assistants. Following in Rubens' footsteps, Van Dyck used drawings to show his staff his visions. Van Dyck would do a sketch and then it was largely left to the assistant to enlarge it and turn it into a finished painting. How much involvement the master had with each work varied from commission to commission. Like Van Dyck, Jacob Jordaens was born in Antwerp to a prosperous merchant family. Unlike Van Dyck and Rubens, Jordaens did not go to Italy to study art. Indeed, throughout his life, he rarely left Antwerp. Jordeans was nonetheless very influenced by Rubens. At that time, Ruebens was Antwerp's leading artist. On occasion, Rubens would employ Jordeans to enlarge and complete works based upon Rubens' concepts. When Rubens died in 1540, Jordeans became Antwerp's leading painter. (Van Dyck by that time was living in England. Moreover, Van Dyck would die in 1641). The exhibit at the Morgan brings together approximately 30 works on paper from these three masters. Most of the works are from the Morgan's collection but there are some works loaned from other collections. Not surprisingly given the relationship between these three artists, there is a great deal of similarity of style. This is perhaps most evident in three studies of male nudes: Rubens' “Seated Male Youth”; Van Dyck's “Study for the Dead Christ”; and Jordeans' “Study of a Male Nude Seen from Behind “ All are works on colored paper using black chalk heightened by white chalk. In each, the muscles are prominent and handled similarly. There are also examples of preparatory sketches depicting scenes with religious themes. These are interesting for the economy of line that the artists used. Jordeans is the only one who used color but then he began his career using watercolor to create designs for tapestries. All of these artists did portraits but of the three, portraiture is most associated with Van Dyck. Indeed, Van Dyck can be said to have been the primary influence on English portraiture for centuries after his death. The exhibit presents one of his portrait sketches. It is a preparatory sketch for a painting that he did of the wife of a fellow artist and her daughter. Van Dyck took great care and precision with regard to the woman's clothes and jewelry. However, the face again has an economy of line. There is no modeling. Instead, he uses lines to suggest the features and shadows. A second portrait highlights the similarity in styles of these artists. “Portrait of a Young Woman” was for centuries attributed to Rubens. However, in the 1980s, that attribution was questioned and now the expert view is that it is one of the few portraits by Jordeans. Certainly, the use of bold lines and contrast is more similar to Jordeans' works elsewhere in the exhibit; Rubens' works are somewhat more vague. In any case, it is one of the most engaging works in the exhibition. I recently participated in a painting class on Norwegian Breakaway. Entitled Canvas By U, these classes are part of the entertainment programming throughout the Norwegian Cruise Line fleet. These painting classes are a popular activity. Guests must sign up beforehand for a class. This is done via a list in the ship's library. The daily program announces the time when the list will open. On the voyage that I was on, the sign-ups began as soon as the staff member in charge of the library arrived in the morning. Within a few minutes, all of the places are usually filled despite the $35 per class fee.. There are only a dozen or so places for each class. I was told that to have more places would dilute the experience as the instructor would not be able to give enough time to each participant. The number of classes held on each cruise varies. Typically, the classes are held on days when the ship is at sea. Therefore, as a general rule, the more sea days on a given cruise, the greater the number of classes. However, the art classes have to compete with other activities for space and staff so it is not automatic that there will be a class on every sea day. Rather than having professional artists teach the classes, Breakaway uses members of the ship's activities staff who have received training in how to present these classes. While their knowledge of art technique may be limited, they are experienced in working with people and in making activities enjoyable. An effort is made to assign the classes to members of the activities staff who have an interest in art but the instructor for any given class could be any member of the activities staff. The class I attended was held in the Headliners comedy club. Two rows of tables with easels and blank canvases were arranged around the small stage. On the stage was a table with a similar set-up. In addition, there was an easel with a completed painting. Each participant's objective in this class was to make his or her own version of the painting displayed on the stage. The instructor emphasized that while everyone would be painting the same subject, each participant's end-product was to be his or her own painting. Therefore, everyone was encouraged to use their creativity and make whatever variations they wanted. The painting that served as the model in my class was a picture of a tropical island at sunset. It had a colorful red sky, ocean, sand and a grove of palm trees. Different paintings are used as the model for different classes. Thus, a guest could participate in several classes without repeating the same painting. The instructor took the class through the process of painting this picture step-by step. Beginning with the island, she pointed out what color(s) to use, how to mix the paint with water, and which brush to use. She then moved on to painting the sky, the sea, and finally the palm trees. To make these paintings, each participant was equipped with a tray with dollops of a half dozen (tempera) colors, two brushes and a 12 by 16 inch canvas board. In addition, each had a disposable apron and gloves. As the participants painted, the instructor moved about making suggestions and encouraging remarks. There was little conversation between the participants as each was very intent on his or her own painting. From what I could gather, most of the people participating in the class had little or no experience with painting. However, all were interested in painting and were keen to experience what it is like to create a painting. Some displayed a natural talent for painting. All seemed to display a sense of accomplishment as the class drew to a close.  “Forgotten Faces” is an exhibit of some 11 portraits at the National Gallery of Ireland by Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Flemish artists done in the 16th and 17th centuries. What binds all of these portraits together is that the identity of the sitters have been lost over time. The signage at the exhibit asserts that the siters had their portraits painted in order to “mark significant events in their lives, to flaunt their wealth, or to reveal their social standing. All wanted to register their existance in a medium that would outlive them.” However, because the names and life stories of the siters have been lost over time, the exhibit asks “what is the significance of such nameless portraits?” It answers that question: “Perhaps their value lies in the fact that they serve as reminders of the brevity of life, and lead us to remember how we want to be remembered, if at all.” Elsewhere, the museum writes: “Ultimately, however, this display of forgotten faces encourages us to consider people's thoughts about time, memory, identity and legacy, and how portraiture provides us with the illusion of permanence in a changing world.” I found myself in fundamental disagreement with the thesis of the exhibition. The significance of a portrait does not come from the identity of the sitter. The world's best known painting, the Mona Lisa, is a portrait and while people may be curious as to who the woman with the mysterious smile is, who she is is irrelevant. Similarly, Van Gogh's portrait of the postmaster of a small French town is not an important painting because of its subject's identity. A successful portrait is one that says something about the person depicted such as their emotions and their personality. It is self-contained. All that we need to know about the subject is contained in the portrait. The sitter's name, life story and other extrinsic facts are irrelevant. A portrait also conveys something about the artist. The image is not a mechanical recreation of how the sitter looked. Rather, it is the person as seen through the artist's eye. It is an image as interpreted through the artist's intellect, emotions and perceptions. Therefore, if the subjects of these paintings were seeking a form of immortality by having their portraits painting, they achieved it. Some 500 years after their time, people are looking at their images and seeing something of their personality. The museum at times appears to realize this point. For example, in “Portrait of a Spanish Noble Woman” by an unknown artist, the signage says: “this is a highly controlled image that reveals what she and the artist wanted to disclose about her place in society.” Thus, the work not only tells us something about the sitter but also about her times. Similarly, in “Portrait of a Man Aged 28”, also by an unknown artist, the signage says: “His youthful hopeful face lends the portrait poignancy.” Thus, it is conceded that this portrait does convey something about the person depected. While the historical facts of that person's life have disappeared, we nonetheless know something about him through the image that the artist created. The sign, however, goes on: “His anomynity is a reminder that our lives exist in the memories of people we know, and these memories can disappear within a generation or two.” But such a conclusion about the fleeting nature of existence does not really follow from the fact that we do not know the name of the person shown in a particular portrait. Even in a well-documented life, we do not know a person to the same degree as his or her friends knew that person. Thus, famous or anoymous, it can be said that our lives only exist in the memories of the people we know. Once again, the degree to which we know extrinsic facts about a person depicted in a portrait is irrelevant to whether that painting speaks to us. Everything that we need to know about that person is contained within the four corners of the portrait. Of course, some artists are better able to capture and communicate something about their subjects than are others. Thus, we find out more about the people depicted in some works than we do from others. The exhibit contains works by some well-known artists such as Veronese and Tintoretto but the works of the unknown artists are often just as moving. Although a small exhibit of second tier works, “Forgotten Faces” is successful because of the thought-provoking discussion of portraiture.  Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, a temporary exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, brings together the works of more than 50 artists to illustrate the contribution of women artists to modern art. The works come from the Museum's collection. Following World War II, the art establishment became dominated by abstract art. Although the artistic community at the time regarded itself as avant garde and progressive, it was not very tolerant of competing ideas. For example, the doors of the galleries were closed to artists working in more traditional or realist styles. So too, the galleries - - and too often the minds of the art world - - were largely closed to women artists even those doing abstract work. In the post war period, there were few, if any, mutual support groups for women artists. Watching my mother's struggle (see Art of Valda), what help she received seemed mostly to come from male artists who she had met while at the Art Students League of New York. Thus, for a woman artists to become recognized during this period was very much an act of individual achievement. This exhibit brings together the works of a number of woman artists who managed to overcome the prejudice of the time. It documents that women indeed contributed to the various schools of abstraction that dominated this period. Although the exhibit presents these works as works of women artists, it is important to note that these artists did not identify themselves as women artists and were not just competing against other women. The goal was to be artists who produced art that would compete in the marketplace of ideas with all other art regardless of the sex of the person who produced it. Perhaps the best known school of abstraction at the time was Abstract Expressionism. The enormous drip paintings of Jackson Pollock are hallmarks of this school. It was widely believed that such monumental works required masculine strength and gestures. However, the exhibit documents that women artists were producing similar works on a large scale. These artists included Lee Krasner, the wife of Jackson Pollock, who is represented in this exhibit by her work “Graea.” The curves of paint in this work have an almost floral, organic look. Abstract expressionism is about emotions and the work I found that evoked more reaction in me was Joan Mitchell's “Ladybug.” I found the color combinations visually pleasing and the lines moving and exciting. I also was impressed by Helen Frankenholer's “Trojan Gates.” Although a large canvas, it seemed more cohesive and unique in its approach than many abstract expressionist pieces. At the opposite end of the spectrum is “Reductive Abstraction.” Here, the idea was to remove the human touch from the work. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was much talk about human isolation and the potential that the mindless application of science would create a sterile environment in the future. Accordingly, some artists created futuristic works based upon mathematical or scientific concepts that were devoid of the human touch. Jo Baer's “Primary Light Group: Red, Green and Blue” is made up of three canvases, each of which is primarily a blank white square. Around the outer edge of each of the squares is a narrow black border. The three canvases differ only in that on one there is the color of the narrow space between the white area and the border. On one it is red; one, it in green; and one it is blue. The concept relies on the work of physicist Ernst Mach on the optical effects of placing colors next to black. I found the work too devoid of emotion. In addition, it reminded me of the demonstrations in high school science class when the teacher would illustrate some principle by using a clever but meaningless gimmick. The exhibit also shows that women artists made contributions in bringing abstraction to textiles. Vera Neuman's “Stone on Stone” made in the 1950s appears to be a forerunner of the designs used in the fashion revolution of the 1960s. A more disquieting work is Magdalena Abakanowicz's “Yellow Abakan,” a large, rumpled piece of fiber that hangs on the wall like the corpses in a butcher's freezer. It is not pretty but it evokes emotion. Finally, the exhibit concludes with Eccentric Abstraction.” These are works where the artist used materials not traditionally used in making art. The challenge in such works is to add enough creativity to the project so that it becomes a work of art rather than a pile of junk. Lee Bonteciu's “Untitled” employs pieces of used canvas conveyor belts to form a swirling, three dimensional object. Its industrial coloring gives it a dark, foreboding feel. Once again, it is not pleasant looking but it is evocative of emotion. This week, I wanted to talk about Claude Moent's “Bathers at La Grenouillere.” which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London.

Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840. His father was a small businessman and the family moved to Le Harve about five years later so that his father could join a wholesale grocery firm that was owned by family members. Thus, Monet came from a middle class background. From an early age, Claude displayed a talent for drawing. Over time, he developed a reputation in Le Harve for his comic drawings and caricatures and was able to derive income from the sale of such works. With such a beginning, one might well expect that Monet would have developed into a portrait painter. However, one day when he went out to watch Eugene Boudin work on a landscape, he realized that landscapes were what he wanted to paint. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.” Friends and family recognized that Monet had talent. However, they were unanimous in saying that he needed to refine that talent by studying in the studio of an established artist. At that time, the most respected artists produced highly polished works with extensive modeling and glazing. The apex of the art world was history painting in which figures were depicted in scenes that told a story. Every artist's ambition was to have a work shown at the prestigious Salon in Paris. Monet was quite independent and bridled against such suggestions. Nonetheless, he went to Paris to study first at the Academie Suisse and later at the studio of Charles Gleyre, an established conventional artist. He did not like the conventional approach to the study of art. Although he often completed works in the studio, Monet preferred to work outdoors, painting directly from nature. However, his time in Gleyre's studio was not wasted because there he met Frederic Bazille and Pierre Auguste Renoir, who would be his compatriots in the Impressionist movement. Despite his dislike of conventional painting, Monet prepared and submitted several works to the Salon during this period. Most were genre paintings depicting contemporary people outdoors. In some respects, these works were reminiscent of Edourard Manet's work, Manet being something of a hero to Monet and his friends. They were more polished and the colors more subdued than Monet's later works. Nonetheless, the Salon rejected Monet's submissions. In the eyes of the juries, the works were unfinished and they failed to tell a story. During these years, Monet was able to sell some paintings but he often spent more than he earned.. Subsidies, first from his aunt and later by Bazille enabled him to continue on as an artist. In 1869, Monet moved with his mistress and young son to a cottage in Saint-Michel near Paris. Renoir was living with his parents nearby and so the two painters would often go out and paint the same subjects together. One of the places they were was La Grenouillere (the Frog Pond) a floating restaurant on the Seine at Bougival. The cafe was attached to a small island and to the riverbank by pontoons. There was a place to moor boats and a place for swimming. It was a very popular venue for socializing and summer fun. Indeed, it achieved such a reputation that Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugene came to have a look. Bathers at La Grenouiller is one of a series of studies Monet made in preparation for a larger more polished work that Monet submitted to the Salon. The larger work was rejected and later lost during World War II. What makes Bathers particularly interesting is that it is a forerunner of the style Monet would use in his later works when he was no longer working with the idea of submitting paintings to the Salon. The artist used color rather than lines to create the image. Figures, water, foliage are all described with a few bold brush strokes. The composition has a snapshot quality - - a scene of everyday life. Monet does not comment on the scene. He does not condemn it as people having frivolous fun nor does he praise it as welcome relief for the everyday worker. He just presents the scene and the viewer can make up his or her own mind. The picture can be dived into four quadrants with the pier dividing the picture horizontally and a vertical line right of center descending from the trees past the boats. Each section is a separate picture. However, the S curve of the river brings the composition together. A painting such as the Bathers would not have been possible only a few years before. The invention of the paint tube in the 1840s enabled Monet to easily transport his palette to the scene. Similarly, the invention of the metal ferrule made flat brushes possible. Such brushes enable Monet to work quickly and their use is documented by the flat brush strokes in this painting. The lesson here being that artists should not be afraid of employing new technology.  On a recent visit to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (ADNS), I was introduced to the works of Maud Lewis. Maud was a talented Canadian folk artist with a compelling story. Indeed, her story is so compelling that recently a movie, “Maudie,” was made about her life. Maud Dowley was born in 1903 in rural Nova Scotia. She was born small and with hardly any chin. These difficulties were compounded when she was stricken with juvenile arthritis causing her joints to swell and deforming her hands. This condition worsened throughout her life. Most likely to avoid the taunts of other children, Maud spent most of her childhood by herself or with her immediate family. She was introduced to art by her mother who painted Christmas cards to supplement the family income. Painting became a passion for Maud. After the death of her parents, Maud lived with her brother and with her aunt for a time. But then in 1938, she married Everett Lewis, an itinerant fish peddler, who she probably met when he made a delivery to her aunt's house. She moved into Everett's tiny house near the local “poor house.” It had no electricity, no indoor plumbing and was heated only by a wood burning stove. Maud's disabilities prevented her from doing the housework so that became Everett's responsibility. Maud concentrated on her paintings. The primary vehicle for selling her art was a roadside sign saying “Paintings for Sale.” Her works were also available through a local store and Everett sold her hand-painted holiday cards from his wagon while making his deliveries of fish. The paintings were sold for a couple of dollars each. Despite the limited reach of these marketing efforts, such was the power of Maud's work that journalists began to write about her and she gradually became known for her art. This enabled her to purchase better quality materials and led to a slight improvement in lifestyle. However, Everett and she continued to live in the same rural community. Maud died in 1970. The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia has a large collection of Maud's works. Maud had no formal art training and her exposure to paintings by others was pretty much limited to what happened to be published in magazines. Thus, her works do not reflect any artistic movement or school of thought. Rather, they are flat images that have the simplicity of the early 19th century North American folk paintings. In some respects, they are similar to the works of Grandma Moses. Maud had a great sense of color and of composition. These combine to form happy images of rural life - - portraits of cats, teams of oxen, covered bridges, horse drawn sleighs, churches, rural landscapes and pictures of the sea shore. Nowhere is there a hint of the difficult life that she endured. Perhaps it would be better to say overcame rather than endured. These images reflect a triumph of the spirit over adversity. This is underscored in the centerpiece of the exhibit - - the house in which Maud and Everett lived for 30 years. After Everett's death, a private group bought the house and donated it to the Province of Nova Scotia. Following several years of conservation work, the house was re-assembled inside of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. It is indeed a tiny house. I have seen children's playhouses that were larger. As mentioned earlier, it had no modern amenities. However, there is a lot of love in this house. Maud painted not just the outside of the house but also the interior including the stove. Images of flowers speak of beauty and happiness. Inside the house, you can see some of the tools Maud used to create her art such as sardine cans that were used in mixing paint. Until she achieved some recognition, her materials were house paint, boat paint and hobby brushes. The Maud Lewis Gallery at the AGNS is thus of interest in two ways. First, there are the paintings themselves. They are pleasing images on a stand alone basis without reference to the artist's story. Second, it tells an inspirational story.  When I was in Dublin, Ireland recently, I had the good fortune to see a small retrospective exhibition of the works of Margret Clarke at the National Gallery of Ireland. Margret Clarke (1884-1961) was a woman artist who achieved success as an artist in the first half of the 20th century. I mention the fact that she was a woman because in those days there was a great deal of prejudice against women and thus for a woman to have achieved success in those days is all the more impressive. Ms. Clarke began her artistic training at Newry Municipal Technical College continuing on to the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (“DMSA”). Her goal was to become an art teacher and she obtained an art teacher certificate in 1907. However, she won numerous scholarships and prizes thus enabling her to embark on a career as a professional artist. Two paintings in the exhibition by her teacher at the DMSA, Sir William Orpen, show Ms. Clarke as having an intelligent face with lively eyes. These same characteristics appear in her self-portrait. Ms. Clarke achieved success as a portrait painter and her subjects include such ntables as the future Irish prime minister Eamon de Valera. The portrait commissions are traditional and somewhat reminiscent of John Singer Sargent's portrait commissions. Her private works, which cover diverse subjects including family portraits, nude studies and genre paintings, are less conservative. You can see influences of artists such as Cezane and El Greco as well as Asian prints. Still, the works that really spoke to me were Ms. Clarke's drawings, mostly graphite on paper but also charcoal on paper. These drawings were technically superb but at the same time sensitive. Her drawing of her husband, the artist and designer Harry Clarke, done around the time of their marriage in 1914 conveys the emotion that she felt for the sitter bringing him alive. Similarly, her sketches of Julia O'Brien, who worked in the Clarke household in the 1920s have unusual sensitivity. They communicate, which to me is the hallmark of good art. Margret Clarke was only the second woman to become a full time member of the Royal Hiberian Academy in 1927. But while she achieved this degree of success during her lifetime, her reputation faded subsequently. This refelects the fact that the art establishment became co-oped by abstraction during the mid to late 20th century. Figurative work was rejected as passe and unintellectual. Such thinking has now been exposed as close-minded nonsense. Therefore, the National Gallery of Ireland's decision to spotlight the work of an artist who has undeservedly been ignored is to be applauded. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed