|

“Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)” at the Met Breuer in New York City surveys 700 years of Western sculpture focusing on works that in one way or another attempt to approximate life. The works occupy two floors of the museum and are drawn from the Met's own collection as well as works on loan from elsewhere.

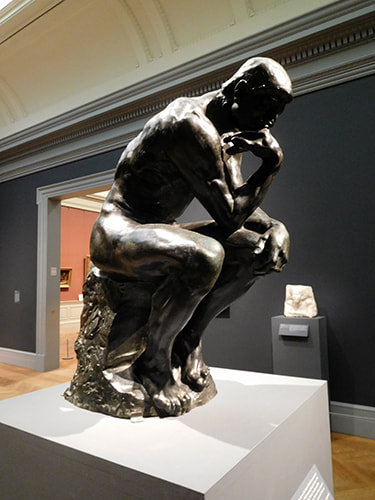

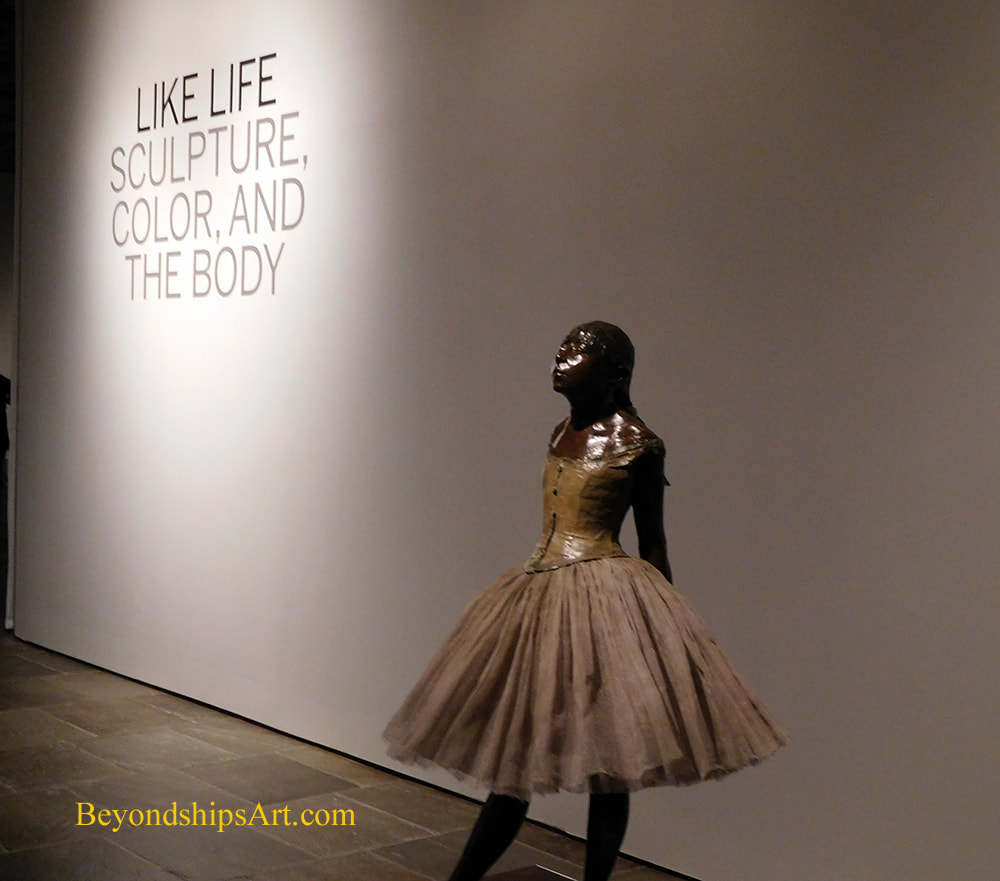

Western sculpture has long depicted the human form. However, at least since Medieval times, the majority of the sculptures of the human body have not tried to convey a life-like appearance. To illustrate, marble statues in museums are usually left white and bronze statues in the park are usually the color of the metal. They are meant as depictions of the human form rather than attempts to re-create a real person. No one would mistake these statues for real people. Throughout this period, however, there have been attempts to cross the border line traditionally observed by sculptors. Most often this has been done by painting the sculpture to give it the color of a real person. However, it has also been done by incorporating elements such as human hair in the sculpture or by dressing the sculpture in clothing. Plastics and similar materials have made it easier to approach a life-like look. This exhibition looks at the various ways sculptors have striven to create a life-like image. There are examples of religious sculptures painted to make the saint or other subject appear alive. A life-like appearance was thought by some to be helpful in persuading viewers to believe. Others, however, condemned such depictions as being akin to idolatry as people might worship the statue rather than the concept behind the statue. Edgar Degas clothed his famous sculpture of a young ballet dancer with an actual ballet costume. While the image is now very familiar, it was unsettling to 19th century viewers when it was first shown in Paris. Sculptures did not wear actual clothing. More recently, artists have not only clothed figures but by using technology and artificial materials have created figures so life-like that the viewer is left wondering whether the figure is really just someone standing still. Beyond the novelty of such statues, they can be used to capture a moment in time when surrounded by furniture or other props.. Traditionally, statues remained in one pose. Mannequins and other figures with movable parts generally were not considered art. However, the exhibition shows that artists have in the past and now have used movable parts in their sculpture. The exhibition does not present the works chronologically but rather by theme. For example, one gallery is devoted to the Pygmalion myth, in which the gods grant a sculptor's wish that the statue that he has created turn into a real woman. The works include a 19th century painting, a series of drawings by Pablo Picasso and John De Andrea's 1980 sculptural scene in which figures made of polyvinyl polychromed in oil depict the artist and his sculpture with life-like detail. “Life-like” is a phrase often used at funerals to describe the mortician's treatment of the corpse. Regardless of how closely a sculpture approximates life, the fact remains that it is not alive. Thus, there is a morbid element to this line of sculpture. In fact, one of the works is a corpse. The 19th century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham specified in his will that after his death his body would be dissected. After that was done, the body was to be preserved and brought out at meetings at the University of London His wishes were followed. Over the years, the head deteriorated and so a wax head was mounted on the body. The clothed body with its wax head is seated in a glass case. The smile indicates that Bentham would have enjoyed the viewers' discomfort. Along the same lines, there are sculptures with blood and/or vital organs showing. The fact that the sculptures are life-like makes these mutilations rather grisly even though no real person was involved. Although sometimes unsettling, overall, this is an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition. The exhibition shows that an inanimate object can be made to appear strikingly like a real person. Yet, oddly enough, in art, the essence of a person often comes through better in a less realistic image. Thus, one is left to ponder what it is that sets a living being apart.  Rodin At The Met is a salute to the sculptor Auguste Rodin on the 100th anniversary of his death. It is an entirely fitting tribute as the then-young museum was a supporter of this artist during his lifetime to the extent of opening a gallery dedicated to his work in 1912. Rodin showed his appreciation by giving the Met additional works. This exhibit of some 50 works includes not only the works that the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired during the artist's lifetime but also works that it has collected subsequently. Auguste Rodin was from a working class family that lived in Paris. He received his basic training in art at the Petit Ecole. However, he was refused admission to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the leading art academy in France. Although this forced Rodin onto a much more difficult road to success, he also avoided indoctrination into the lifeless Neo-classical style that was the trademark of that school. Instead, Rodin slowly built his own style along with his reputation, first as an apprentice to other artists and then on his own. One turning point was his visit to Italy in 1876 during which he was very impressed by the sculptures of Michelangelo. Even after he achieved fame, Rodin's style was not what people expected. There is story after story of how individuals and public authorities commissioned works only to be shocked by Rodin's final product. Those that were rejected are now recognized as some of the greatest works of 19th century art. Rodin found fame in the United States after some of his works were displayed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Here again, some of his works were found so shocking that they were exhibited behind a curtain in an area that required special permission to enter. However, private collectors and museums were soon purchasing his works. The Met has casts of several of Rodin's best known pieces including The Thinker, the companion sculptures Adam and Eve, the Age of Bronze and a study for the Monument to Balzac. Rodin modeled his sculptures in clay. Plaster casts were then made to preserve the sculpture. From these, bronze casts were made or marble carved often by studio assistants. This explains why the same work can appear in multiple museums. There is a discernible difference between Rodin's bronzes and marbles. You can see the power of the sculptor's fingers working the underlying clay in the bronzes. The marbles tend to be less distinct, smoother and gauzier, almost dream-like. In either case, you can clearly see Rodin's works were a clear break from the allegorical figures and gods and goddess so popular at the time. While some have titles that relate back to mythology or the bible, these works are of real people with real emotion. A particularly fascinating part of this exhibit is Rodin's works on paper. In addition to sculpture, Rodin also did watercolors and drawings. Some of these were in preparation for sculptures but mostly they were another means of communication. It is said that Rodin would draw without removing the pen from the paper and without taking his eyes off the model. The results were images that border on abstraction and which are full of emotion. Along with Rodin's works, the Met has hung examples of works done by his friends. One such friend was Claude Monet who also was leading a revolution in art in 19th century France. The two artists held a joint exhibition in 1889. These contemporary works help to place Rodin's works in context “Calder: Hyermobility” at the Whitney Museum of American Art is an exhibit of sculptures by Alexander Calder. It focuses on the importance of motion in Calder's work.

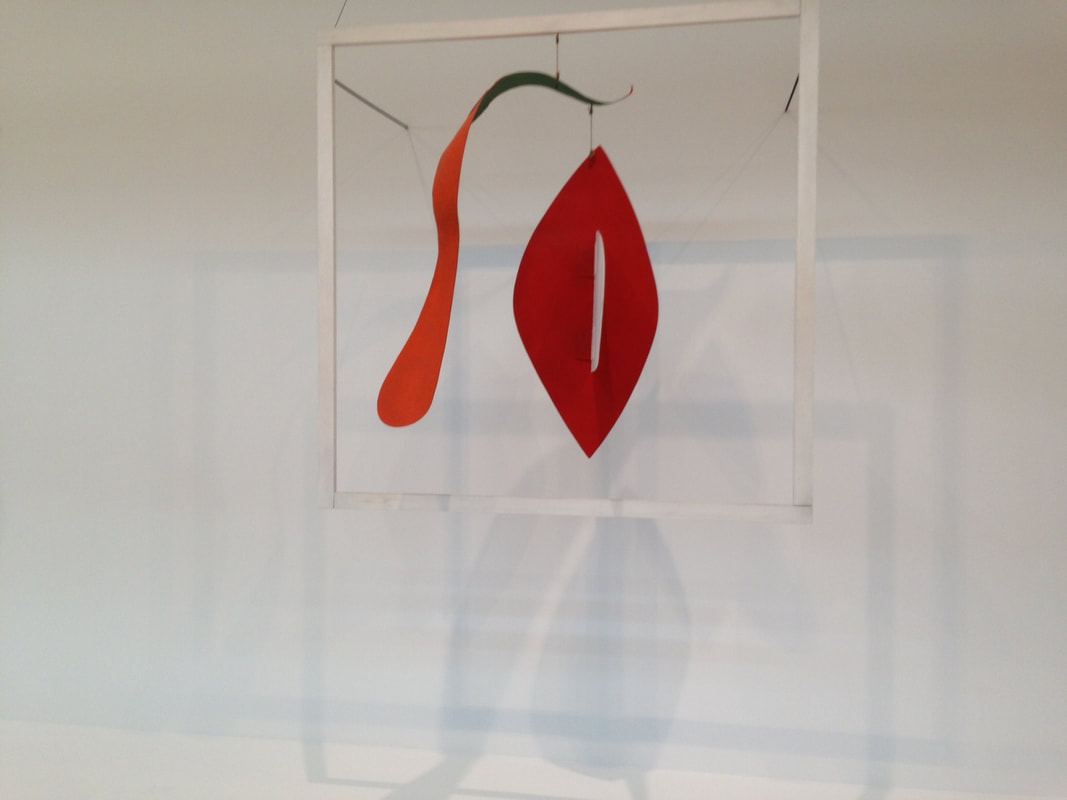

Alexander Calder came from an artistic family. His father and grandfather were both sculptors. His mother was a professional portrait painter. Not surprisingly, Calder did art work from an early age and even had studios in the basements of several of the houses that the family occupied while he was growing up. Knowing the difficulties associated with being a professional artist, his family did not encourage Calder to follow in their footsteps. Instead, he studied to be become a mechanical engineer. Following his graduation from the Stevens Institute in 1919, Calder held a variety of jobs including being a hydraulic engineer and working as a mechanic on a steam ship. Calder, however, found this work unsatisfying and decided to make art his career. To this end, he enrolled in the Art Students League in New York. In 1926, he moved to Paris where he established a studio and became friends with a number of avant garde artists. Following a visit to Piet Mondrian's studio, he decided to embrace abstract art. During this period, Calder became interested in creating sculptures with movable parts. His early works along this line moved by cranks and motors, perhaps reflecting his engineering background. By the early 1930s, Calder had returned to the United States and his works were less mechanical. Instead, the works moved either in response to touch or to the wind. Marcel Duchamp coined the term “mobiles” to describe Calder's sculptures. The Whitney exhibit includes several of Calder's mobiles. Some are freestanding while others are suspended from the ceiling. Even when they are static - - which they are most of the time - - the graceful lines and pure colors of these sculptures make them appealing. At specified times during the day, a staff member appears and “activates” some of the sculptures. Typically, this is done by giving one part of the sculpture a gentle push setting it in motion. The movement causes the image that the viewer is seeing to change. Whereas a portion of the sculpture was say pointing in one direction originally, it points in a number of different directions as it moves. As a result, the overall shape of the sculpture changes, becoming a new image. In addition to the mobiles, the Whitney has one of Calder's large static sculptures in the center of the exhibit. These Calder sculptures were dubbed “stabiles” by Jean Arp in 1932 to distinguish them from Calder's mobiles. With a stabile, the image changes as the viewer moves around the object. In this, the process is not different than traditional sculpture. However, here the forms are abstract - - graceful arches arising from seemingly delicate points. Over the last 90 years or so, the public has become familiar with abstract sculpture. However, the elegance of Calder's designs, both static and kinetic, are such as to have enduring appeal. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed