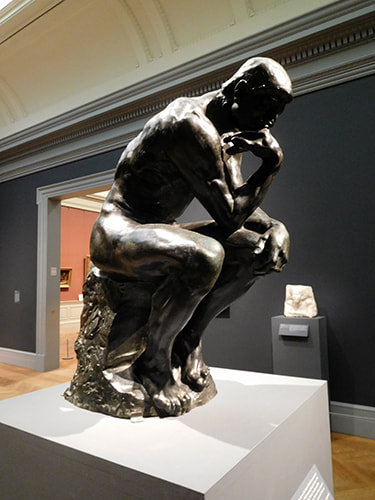

“Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a large exhibition that places in context much of the art created in France from the French Revolution to World War I. It explains why so much attention was paid by artists such as the Impressionists to the out doors as a subject. Extending from the late 18th century through the 19th century a passion developed in France for parks and gardens. Several factors came together to fuel this passion. First, as a result of the French Revolution, the parks and hunting reserves that had heretofore been open only to royalty and the aristocracy, became open to everyone. This access helped to open the eyes of the public to the beauties of nature. Second, the Industrial Revolution also changed the character of society. The middle class grew and people had more leisure time. They wanted green spaces, both public parks and private gardens, where they could escape from the stresses and pollution that were the less attractive side effects of industrialization. Accordingly, in the grand re-design of Paris that took place in the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann included tree-lined boulevards and some 30 parks and squares. Other cities and towns throughout France followed suit. Third, it was also a period of exploration and travel. Exotic plants were being brought back to France, stirring the public imagination. The Empress Josephine, first wife of Napoleon, and a celebrity in her day, spurred public interest in such plants by making her greenhouse at Malmaison a horticulture hub for exotic species. Artists were not immune from these forces. The natural world, depicted in landscapes and in still lifes, had long been a subject for art. However, a new enthusiaum developed. The painters of the Barbizon School took inspiration from the former royal hunting grounds at Fontainebleau. Later, the Impressionists, whose aims included depicting scenes of modern life, reflected public's passion for parks, gardens and the natural world in their works. While this exhibition includes earlier works, the Impressionists and the artists that they influenced dominate the exhibition. For example, in the gallery “Parks for the Public,” we see works by Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and others of former royal hunting reserves. However, you also have masterpieces by Calude Monet and Camille Pissaro of city parks in Paris. There is also a wonderful watercolor by Berthe Morrisot “A Woman Seated at a Bench on the Avenue du Bois” as well as a study by Pointillist George Seurat for “"A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." In the gallery “Private Gardens,” the works reflect the fact that people wanted to have their own green spaces where they could cultivate plants and escape from the outside world. Many artists were also amateur gardeners during this period. Of course, the dominant figure here is Claude Monet who was painting garden scenes long before he created his famous garden at Giverney. However, lesser known watercolors of garden scenes by Renoir and by Cezanne should not be overlooked. With regard to portraiture, we see that the artists blurred the distinction between portraits and genre painting. They are both depictions of individuals and scenes of everyday life. As a result, the identity of the sitter is no longer paramount if important at all to the success of the work. Furthermore, nature is an equal partner in these scenes, not just a background. To illustrate, Edouard Manet's “The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil” is a portrait of Monet and his family. The figures are arranged in a relaxed manner rather than in traditional portrait poses. Thus, it is also a scene of everyday life. Moreover, it would be just as successful if the figures were an unidentified family because it is a captivating garden scene. The passion for nature also brought about a revival of interest in floral still life painting. The exhibition presents examples by Manet, Monet, Cassat, Degas, and Matisse to name a few. But Vincent Van Goghs paintings of sunflowers and irises attract the most viewers. Given the popularity of the Impressionists and their broader circle, one would expect any exhibit in which they are prominent to be successful. However, the Met has done a good job here of supporting the theme of the exhibition. In addition to the paintings, there are drawings, prints contemporary photographs and objects relating to this theme. The signage is also good.  Rodin At The Met is a salute to the sculptor Auguste Rodin on the 100th anniversary of his death. It is an entirely fitting tribute as the then-young museum was a supporter of this artist during his lifetime to the extent of opening a gallery dedicated to his work in 1912. Rodin showed his appreciation by giving the Met additional works. This exhibit of some 50 works includes not only the works that the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired during the artist's lifetime but also works that it has collected subsequently. Auguste Rodin was from a working class family that lived in Paris. He received his basic training in art at the Petit Ecole. However, he was refused admission to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the leading art academy in France. Although this forced Rodin onto a much more difficult road to success, he also avoided indoctrination into the lifeless Neo-classical style that was the trademark of that school. Instead, Rodin slowly built his own style along with his reputation, first as an apprentice to other artists and then on his own. One turning point was his visit to Italy in 1876 during which he was very impressed by the sculptures of Michelangelo. Even after he achieved fame, Rodin's style was not what people expected. There is story after story of how individuals and public authorities commissioned works only to be shocked by Rodin's final product. Those that were rejected are now recognized as some of the greatest works of 19th century art. Rodin found fame in the United States after some of his works were displayed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Here again, some of his works were found so shocking that they were exhibited behind a curtain in an area that required special permission to enter. However, private collectors and museums were soon purchasing his works. The Met has casts of several of Rodin's best known pieces including The Thinker, the companion sculptures Adam and Eve, the Age of Bronze and a study for the Monument to Balzac. Rodin modeled his sculptures in clay. Plaster casts were then made to preserve the sculpture. From these, bronze casts were made or marble carved often by studio assistants. This explains why the same work can appear in multiple museums. There is a discernible difference between Rodin's bronzes and marbles. You can see the power of the sculptor's fingers working the underlying clay in the bronzes. The marbles tend to be less distinct, smoother and gauzier, almost dream-like. In either case, you can clearly see Rodin's works were a clear break from the allegorical figures and gods and goddess so popular at the time. While some have titles that relate back to mythology or the bible, these works are of real people with real emotion. A particularly fascinating part of this exhibit is Rodin's works on paper. In addition to sculpture, Rodin also did watercolors and drawings. Some of these were in preparation for sculptures but mostly they were another means of communication. It is said that Rodin would draw without removing the pen from the paper and without taking his eyes off the model. The results were images that border on abstraction and which are full of emotion. Along with Rodin's works, the Met has hung examples of works done by his friends. One such friend was Claude Monet who also was leading a revolution in art in 19th century France. The two artists held a joint exhibition in 1889. These contemporary works help to place Rodin's works in context This week, I wanted to talk about Claude Moent's “Bathers at La Grenouillere.” which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London.

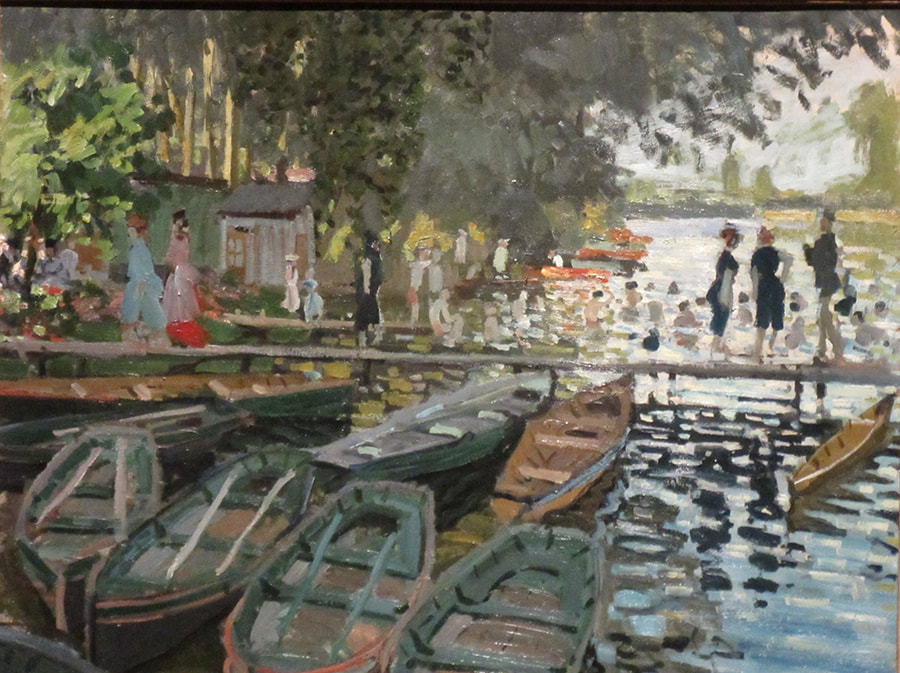

Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840. His father was a small businessman and the family moved to Le Harve about five years later so that his father could join a wholesale grocery firm that was owned by family members. Thus, Monet came from a middle class background. From an early age, Claude displayed a talent for drawing. Over time, he developed a reputation in Le Harve for his comic drawings and caricatures and was able to derive income from the sale of such works. With such a beginning, one might well expect that Monet would have developed into a portrait painter. However, one day when he went out to watch Eugene Boudin work on a landscape, he realized that landscapes were what he wanted to paint. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.” Friends and family recognized that Monet had talent. However, they were unanimous in saying that he needed to refine that talent by studying in the studio of an established artist. At that time, the most respected artists produced highly polished works with extensive modeling and glazing. The apex of the art world was history painting in which figures were depicted in scenes that told a story. Every artist's ambition was to have a work shown at the prestigious Salon in Paris. Monet was quite independent and bridled against such suggestions. Nonetheless, he went to Paris to study first at the Academie Suisse and later at the studio of Charles Gleyre, an established conventional artist. He did not like the conventional approach to the study of art. Although he often completed works in the studio, Monet preferred to work outdoors, painting directly from nature. However, his time in Gleyre's studio was not wasted because there he met Frederic Bazille and Pierre Auguste Renoir, who would be his compatriots in the Impressionist movement. Despite his dislike of conventional painting, Monet prepared and submitted several works to the Salon during this period. Most were genre paintings depicting contemporary people outdoors. In some respects, these works were reminiscent of Edourard Manet's work, Manet being something of a hero to Monet and his friends. They were more polished and the colors more subdued than Monet's later works. Nonetheless, the Salon rejected Monet's submissions. In the eyes of the juries, the works were unfinished and they failed to tell a story. During these years, Monet was able to sell some paintings but he often spent more than he earned.. Subsidies, first from his aunt and later by Bazille enabled him to continue on as an artist. In 1869, Monet moved with his mistress and young son to a cottage in Saint-Michel near Paris. Renoir was living with his parents nearby and so the two painters would often go out and paint the same subjects together. One of the places they were was La Grenouillere (the Frog Pond) a floating restaurant on the Seine at Bougival. The cafe was attached to a small island and to the riverbank by pontoons. There was a place to moor boats and a place for swimming. It was a very popular venue for socializing and summer fun. Indeed, it achieved such a reputation that Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugene came to have a look. Bathers at La Grenouiller is one of a series of studies Monet made in preparation for a larger more polished work that Monet submitted to the Salon. The larger work was rejected and later lost during World War II. What makes Bathers particularly interesting is that it is a forerunner of the style Monet would use in his later works when he was no longer working with the idea of submitting paintings to the Salon. The artist used color rather than lines to create the image. Figures, water, foliage are all described with a few bold brush strokes. The composition has a snapshot quality - - a scene of everyday life. Monet does not comment on the scene. He does not condemn it as people having frivolous fun nor does he praise it as welcome relief for the everyday worker. He just presents the scene and the viewer can make up his or her own mind. The picture can be dived into four quadrants with the pier dividing the picture horizontally and a vertical line right of center descending from the trees past the boats. Each section is a separate picture. However, the S curve of the river brings the composition together. A painting such as the Bathers would not have been possible only a few years before. The invention of the paint tube in the 1840s enabled Monet to easily transport his palette to the scene. Similarly, the invention of the metal ferrule made flat brushes possible. Such brushes enable Monet to work quickly and their use is documented by the flat brush strokes in this painting. The lesson here being that artists should not be afraid of employing new technology. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed