|

Click here for our review of "The Scottish Colourists" at the Kelvin Grove Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow, Scotland.

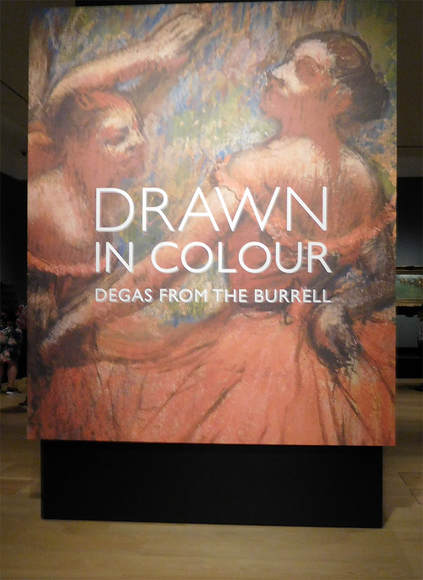

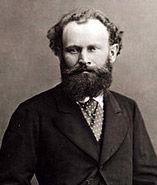

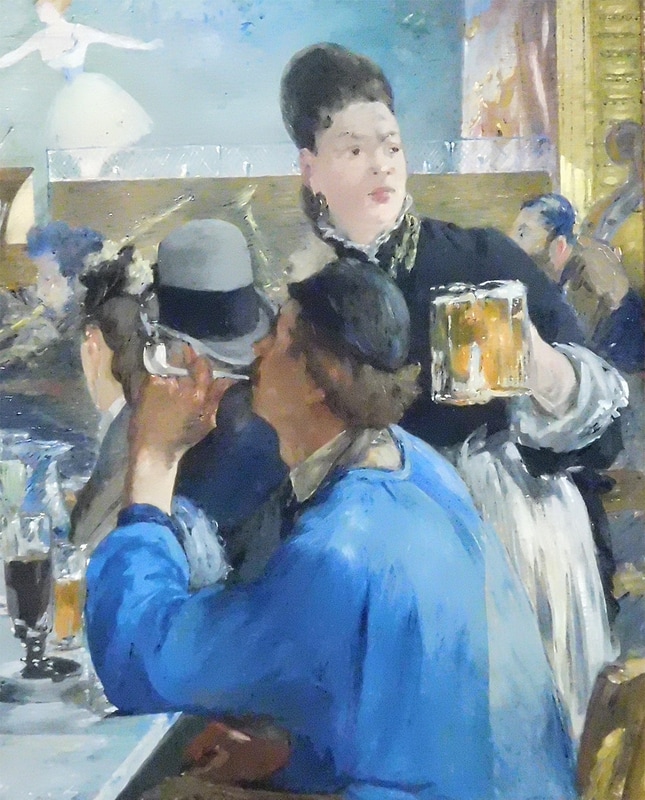

“Drawn In Colour: Degas From the Burrell” recat London's National Gallery brought together 20 works by Edgar Degas from Glasgow's Burrell Collection Gallery along with a number of works from the National Gallery's own collection. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born in Paris in 1834. His father was a French banker and his mother was from a New Orleans Creole family. His father was interested in the arts and encouraged Edgar's interest, often accompanying him to museums in Paris. Indeed, after Edgar made an unsuccessful attempt to fulfill his father's desire that he pursue a career in law, his father provided him with an art studio. Edgar's training in art was quite conventional. He studied at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts including drawing with Louis Lamothe, a disciple of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who Edgar greatly admired. He also traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. In both France and Italy, much of his time was spent copying masterpiece paintings and drawings. With this background, it is not surprising that Edgar's early work was influenced by conventional thinking about art. In those days, history painting was considered the highest form of fine art and so Edgar did history paintings. He also submitted and had works accepted by the Salon, the apex of the art establishment. Soon, however, Edgar's work became quite unconventional. Several factors contributed to this change. In 1864, he met Edouard Manet while he was copying a painting at the Louvre. They became good friends and Edgar came to share Manet's interest in depicting modern life. Following, the death of his father in 1873, Edgar sold off most of his assets in order to pay debts that had been amassed by his brother. As a result, Edgar, who was now spelling his last name “Degas”, had to rely on the sale of his art work to make his living. The primary factor in the evolution of Degas' work, however, was his quick mind. While he always retained his admiration for the great painters of the past, Degas was continually innovating. Diverse inspirations such as Japanese art and the new technology of photography influenced his compositions. He was interested in experimenting with different mediums, branching into photography, sculpture and, most particularly, pastels, which he applied in complex layers and textures. Although often conservative in his thinking on other matters, his thinking on art became quite radical. In 1874, he joined together with several other artists who were taking unconventional approaches to art for an exhibition. The group came to be known as the “Impressionists,” a label Degas hated. Degas helped organize the Impressionist exhibitions and exhibited in all but one of the Impressionist exhibitions. Degas added another dimension to Impressionism. Whereas his colleagues Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro mostly painted landscapes, Degas was interested primarily in the human figure. Whereas the other Impressionists preferred to work outdoors capturing what they were observing at the moment, Degas preferred to work in his studio, sometimes working from photographs or from memory. What connects Degas to the others, however, is an interest in depicting modern life, an interest in light and an interest in using color in unconventional ways. Because there were profound differences in the individual Impressionist's artistic philosophies and because the group included some difficult personalities (including Degas) the group eventually separated. There were only eight Impressionist exhibitions and after 1886, the artists went their separate ways. Degas, who was having problems with his eye-sight, became particularly solitary. Increasingly, he turned to pastels and sculpture. Again and again, he returned to certain subjects such as dancers, horse racing and women bathing. He died in 1917. Sir William Burrell (1861 - 1958) amassed 20 major works by Degas including works from every period of the artist's life. He donated these along with some 9,000 other works of art to the City of Glasgow in 1944. The closing of the Burrell Collection Gallery in Glasgow for renovation provided an opportunity for the Degas to be exhibited in London. The exhibition was presented in three sections: Modern Life; Dancers and Private Worlds - - in short three of Degas' signature subject matters. Although there were a few oil paintings and drawings, most of the works in the exhibition were pastels, Degas' favorite medium The presentation of these works together served to underscore how much of an innovator Degas was. His use of this medium was much different than conventional pastels. The strokes are vigorous conveying energy. The shapes verge on the abstract at times. The colors are often strong and bold.  “Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a large exhibition that places in context much of the art created in France from the French Revolution to World War I. It explains why so much attention was paid by artists such as the Impressionists to the out doors as a subject. Extending from the late 18th century through the 19th century a passion developed in France for parks and gardens. Several factors came together to fuel this passion. First, as a result of the French Revolution, the parks and hunting reserves that had heretofore been open only to royalty and the aristocracy, became open to everyone. This access helped to open the eyes of the public to the beauties of nature. Second, the Industrial Revolution also changed the character of society. The middle class grew and people had more leisure time. They wanted green spaces, both public parks and private gardens, where they could escape from the stresses and pollution that were the less attractive side effects of industrialization. Accordingly, in the grand re-design of Paris that took place in the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann included tree-lined boulevards and some 30 parks and squares. Other cities and towns throughout France followed suit. Third, it was also a period of exploration and travel. Exotic plants were being brought back to France, stirring the public imagination. The Empress Josephine, first wife of Napoleon, and a celebrity in her day, spurred public interest in such plants by making her greenhouse at Malmaison a horticulture hub for exotic species. Artists were not immune from these forces. The natural world, depicted in landscapes and in still lifes, had long been a subject for art. However, a new enthusiaum developed. The painters of the Barbizon School took inspiration from the former royal hunting grounds at Fontainebleau. Later, the Impressionists, whose aims included depicting scenes of modern life, reflected public's passion for parks, gardens and the natural world in their works. While this exhibition includes earlier works, the Impressionists and the artists that they influenced dominate the exhibition. For example, in the gallery “Parks for the Public,” we see works by Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and others of former royal hunting reserves. However, you also have masterpieces by Calude Monet and Camille Pissaro of city parks in Paris. There is also a wonderful watercolor by Berthe Morrisot “A Woman Seated at a Bench on the Avenue du Bois” as well as a study by Pointillist George Seurat for “"A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." In the gallery “Private Gardens,” the works reflect the fact that people wanted to have their own green spaces where they could cultivate plants and escape from the outside world. Many artists were also amateur gardeners during this period. Of course, the dominant figure here is Claude Monet who was painting garden scenes long before he created his famous garden at Giverney. However, lesser known watercolors of garden scenes by Renoir and by Cezanne should not be overlooked. With regard to portraiture, we see that the artists blurred the distinction between portraits and genre painting. They are both depictions of individuals and scenes of everyday life. As a result, the identity of the sitter is no longer paramount if important at all to the success of the work. Furthermore, nature is an equal partner in these scenes, not just a background. To illustrate, Edouard Manet's “The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil” is a portrait of Monet and his family. The figures are arranged in a relaxed manner rather than in traditional portrait poses. Thus, it is also a scene of everyday life. Moreover, it would be just as successful if the figures were an unidentified family because it is a captivating garden scene. The passion for nature also brought about a revival of interest in floral still life painting. The exhibition presents examples by Manet, Monet, Cassat, Degas, and Matisse to name a few. But Vincent Van Goghs paintings of sunflowers and irises attract the most viewers. Given the popularity of the Impressionists and their broader circle, one would expect any exhibit in which they are prominent to be successful. However, the Met has done a good job here of supporting the theme of the exhibition. In addition to the paintings, there are drawings, prints contemporary photographs and objects relating to this theme. The signage is also good.  Drawn to Greatness, Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection is the largest collection of drawings yet to be exhibited at the Morgan Library and Museum and includes some 150 works. However, beyond the quantity of works, this exhibit is important because of the quality of the works. The artists represented in the exhibit are a Who's Who of western art from the Renaissance to the 20th century. Consequently, works of beauty and excellence unfold as you walk through the galleries. The exhibit is drawn from the Thaw Collection, a gift of some 400 sheets by Eugene and Clare Thaw. It was amassed over the last 50 years by Mr. Thaw, an art dealer and collector. Interestingly, Mr. Thaw began his career handling the works of contemporary artists only later expanding into Old Masters. Mrs. Thaw encouraged her husband to keep some of the drawings that he was particularly enthusiastic about and so the collection was born. Works from the Renaissance are the earliest works in the exhibit. As the signage at the exhibit tells us, this was when artistic drawing changed from mechanically recording an image to intellectually creating an image. The exhibit then proceeds chronologically through the centuries, revealing the many ways artists used drawing to create images. The term drawing is used here in its broadest sense. It does not just encompass black and white images done with graphite or charcoal. Rather, the exhibit shows that there are many forms of drawing often involving color. These include pastels, watercolor, inks, chalks, and even oil paint to name a few mediums. Indeed, I was struck by how artists in the 18th century would use several different mediums in their works. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line, this multi-medium practice became lost so that today on social media an artist can be accused of “cheating” if a work contains say both gouache and watercolor. The works here include finished pieces as well as works done in preparation for a painting or mural. However, because the drawings were often for the artist's personal use they are sometimes more revealing than works produced for sale as they are not as tempered by the need to please the tastes of the market. Turner's “The Pass of St. Goddard,” for example, is a swirling mass of colors that is closer to abstraction than realism. Still, the drawings bear the hallmarks of the style which is associated with each artist. To illustrate, an Ingres' drawing looks like an Ingres portrait. You do not need to look at the signage to tell if a drawing was done by Picasso. As a result, the exhibit is a condensed survey of the major ideas in European art. I found myself spending the most time with the late 19th century French masters. Degas is known for his pastels and so it was not surprising to find several of them on exhibit. But there was also a rare black and white drawing by Monet, the master of color. There are also delightful watercolors by Renoir and Morisot. The innovative works by Cezanne take watercolor in a different direction. In addition to being an important exhibition for art lovers, I would also recommend this exhibit to those who make art. It is perhaps easier to push back the curtain and analyze how a work was done with a drawing as opposed to a finished painting.  This week, I thought I would talk about Edouard Manet's Corner of a Cafe Concert, a painting which I saw in the National Gallery in London. I like Manet's work not just because it is pleasing to the eye but because it conveys emotion. I particularly like his ability to make faces thought provoking. Edouard Manet was a French artist born in 1832 in Paris. His father was a successful jurist while his mother was the daughter of a diplomat. His parents wanted him to enter one of the respectable professions rather than pursue his love of art. It was not until after Manet had failed his entrance exams for the naval academy that his family relented and allowed him to study art. While his family's resistance to his desired career must have been emotionally difficult for the young Manet, his family background provided a firm foundation for his art. Because he was financially secure, he was able to travel around Europe to view the works of past masters and to avoid starvation in the process of establishing himself as a successful artist. Manet was a man of contrasts and contradictions. He is widely acknowledged as setting art on a new course and has been called the first modern artist. Yet, he was influenced by and drew from traditional artists such as Velazquez and Goya. He scandalized the art establishment of the day by submitting works such as Dejuner sur iHerbe and Olympia to the Salon but accepted the honors of the establishment such as a medal from the Salon as well as the Legion of Honor. He was a friend of the Impressionists and influenced their work but rejected their invitations to exhibit with them preferring instead to try to have his works accepted by the Salon. An opponent of Napoleon III and a republican intellectual, Manet nonetheless joined the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War rather than flee the country as some of the artists in his circle did. Along the same lines, Manet's artistic style encompasses diverse elements. He favored broad, strong brush strokes and alla prima painting where the forms are rendered by the application of raw color rather than modeled in multiple glazed layers as was done in the popular art of the time. At the same time, his use of black paint recalls the aforementioned Spanish masters. Manet was a painter of modern life but at the same time, there are echoes of Renaissance masterpieces in his works. Corner of a Cafe Concert presents a scene of modern life. Manet enjoyed going to the Parisian cafes that were becoming popular in the 19th century and often sketched scenes that he saw there. This painting, created around 1878, is of a scene at the Brasserie de Reichshoffen. The image is not unlike a snap shot or a photo taken with an iPhone. We see people drinking and enjoying themselves while a dancer performs on stage. You can almost here the clinking of glasses, laughter and the music. In the end, however, the painting is a portrait. The central figure is a waitress who is in the process of serving mugs of beer. Hers is the only face that can be seen clearly in the picture. Something has distracted her and she is looking off beyond the bounds of the canvas. Perhaps someone is signaling her for a drink, perhaps people are arguing, or perhaps someone she knows has walked into the cafe. Whatever it is, she is lost in thought. The drinkers, conversation, the show are as irrelevant to her as she is to them. Thus, she is both at the center of the scene but at the same time not really part of the scene. The face of the waitress is quite simply done. There is very little detail or modeling. The eyes and nostrils are the most dominate and appear to be touches of burnt umber. The same color, perhaps thinned mixed with white was used in several of the other features. In her hand is a large beer mug. It too is simply done. A few strokes of white paint here and there make up the boundaries of the glass. Splashes of yellow ochre and burnt sienna depict the contents. Another thing that I noticed about this work is the use of rectangles. The upper portion of the picture - - the area framing the waitress' face - - is made up of a series of rectangles. They form the stage where the dancer who is off to the left is performing. However, these flat spaces also form an abstract design similar to those used as the subject of paintings by artists in the first half of the 20th century. Corner of a Cafe Concert was originally part of a larger work. At one point during its creation, Manet decided to cut the work in two. He then developed the two halves independently. I like knowing this because it lends a master's approval to the notion of physically altering a work. Sometimes when I am doing a picture, I reach a point where I realize that the picture as a whole does not really work. However, there are some nice bits that could work on a stand alone basis if only they had been created on their own canvas or piece of paper. What Manet has done here shows that it is perfectly permissible to cut down a work physically in order to create a picture that does work. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed