“Forgotten Faces” is an exhibit of some 11 portraits at the National Gallery of Ireland by Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Flemish artists done in the 16th and 17th centuries. What binds all of these portraits together is that the identity of the sitters have been lost over time. The signage at the exhibit asserts that the siters had their portraits painted in order to “mark significant events in their lives, to flaunt their wealth, or to reveal their social standing. All wanted to register their existance in a medium that would outlive them.” However, because the names and life stories of the siters have been lost over time, the exhibit asks “what is the significance of such nameless portraits?” It answers that question: “Perhaps their value lies in the fact that they serve as reminders of the brevity of life, and lead us to remember how we want to be remembered, if at all.” Elsewhere, the museum writes: “Ultimately, however, this display of forgotten faces encourages us to consider people's thoughts about time, memory, identity and legacy, and how portraiture provides us with the illusion of permanence in a changing world.” I found myself in fundamental disagreement with the thesis of the exhibition. The significance of a portrait does not come from the identity of the sitter. The world's best known painting, the Mona Lisa, is a portrait and while people may be curious as to who the woman with the mysterious smile is, who she is is irrelevant. Similarly, Van Gogh's portrait of the postmaster of a small French town is not an important painting because of its subject's identity. A successful portrait is one that says something about the person depicted such as their emotions and their personality. It is self-contained. All that we need to know about the subject is contained in the portrait. The sitter's name, life story and other extrinsic facts are irrelevant. A portrait also conveys something about the artist. The image is not a mechanical recreation of how the sitter looked. Rather, it is the person as seen through the artist's eye. It is an image as interpreted through the artist's intellect, emotions and perceptions. Therefore, if the subjects of these paintings were seeking a form of immortality by having their portraits painting, they achieved it. Some 500 years after their time, people are looking at their images and seeing something of their personality. The museum at times appears to realize this point. For example, in “Portrait of a Spanish Noble Woman” by an unknown artist, the signage says: “this is a highly controlled image that reveals what she and the artist wanted to disclose about her place in society.” Thus, the work not only tells us something about the sitter but also about her times. Similarly, in “Portrait of a Man Aged 28”, also by an unknown artist, the signage says: “His youthful hopeful face lends the portrait poignancy.” Thus, it is conceded that this portrait does convey something about the person depected. While the historical facts of that person's life have disappeared, we nonetheless know something about him through the image that the artist created. The sign, however, goes on: “His anomynity is a reminder that our lives exist in the memories of people we know, and these memories can disappear within a generation or two.” But such a conclusion about the fleeting nature of existence does not really follow from the fact that we do not know the name of the person shown in a particular portrait. Even in a well-documented life, we do not know a person to the same degree as his or her friends knew that person. Thus, famous or anoymous, it can be said that our lives only exist in the memories of the people we know. Once again, the degree to which we know extrinsic facts about a person depicted in a portrait is irrelevant to whether that painting speaks to us. Everything that we need to know about that person is contained within the four corners of the portrait. Of course, some artists are better able to capture and communicate something about their subjects than are others. Thus, we find out more about the people depicted in some works than we do from others. The exhibit contains works by some well-known artists such as Veronese and Tintoretto but the works of the unknown artists are often just as moving. Although a small exhibit of second tier works, “Forgotten Faces” is successful because of the thought-provoking discussion of portraiture. “Poussin, Claude and French Drawing in the Classical Age,” an exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, looks at the role of drawing during one of the peak periods in French culture.

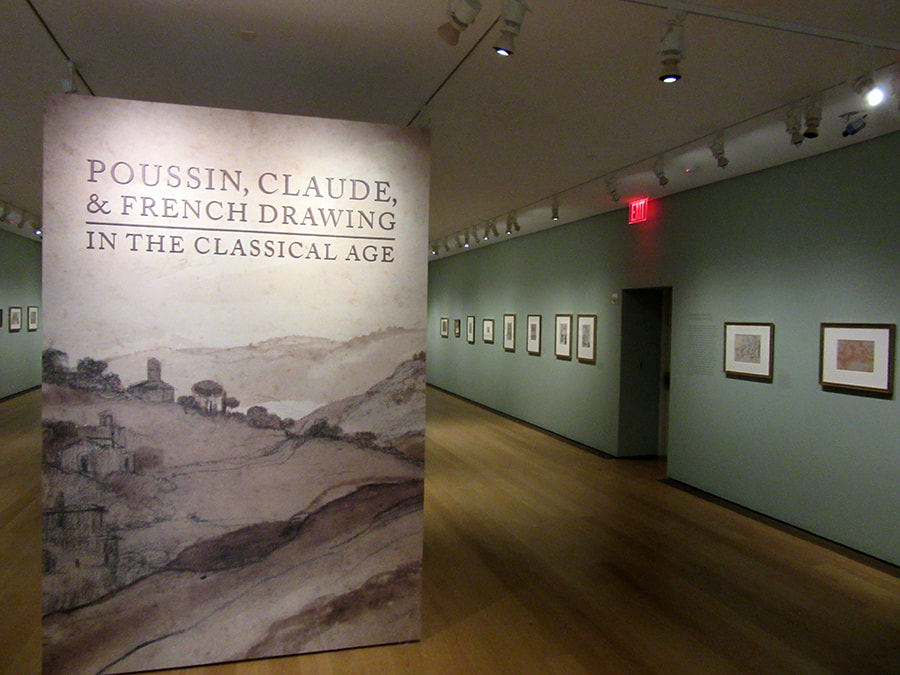

Although France had long been a powerful European nation, it rose to new heights in the 17th century during the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV. In essence, it became the leading power in Europe politically and militarily. At the same time, the arts flourished under the patronage of the French royal court and the ducal court of Lorraine, then an independent nation but later to become part of France. During this time, French artists often traveled to Rome to study both the work of the ancients asforma well as the Italian Renaissance masters. When they returned to France, they brought with them new ideas that stimulated the native talent. As a result, Paris became a center for artistic activity. Drawings served three purposes. First, artists often made drawings to capture scenes that they encountered. Afterall, they did not have iPhones. Second, drawing were used to make studies in preparation for paintings and other more complex works. Third, drawings were done as completed works. This was often the case with portrrait drawings, which members of the court collected and placed into albums. Two of the most important French artists of this period were Nicolas Poussin and Claude Gelleee – better known as Claude Lorrain. Poussin was from France but first achieved success in Rome. In fact, he only returned to France because he was summoned home by the King and then he only remained there for two years. Poussin was very interested in classical antiquity and his work often focused on classical mythology, history and biblical scenes. His drawings were done in preparation for his paintings. The drawings in the exhibit show that he felt free to use a looser style that at time borders on the abstract in his drawings rather than the more precise style of his paintings. Claude Lorrain also studied in Rome and also eventually returned to settle in that city. Lorrain was interested in nature as a manifestation of the divine. He would do sketches directly from nature but he would alsoDaniel rearrange features in his finished landscapes to accord with idealized principles. I found his more free flowing sketch style more appealing than his more formal finished style. Poussin and Lorrain are not the only artists represented in this exhibit. We see that other artists were heavily influenced by classicism while at the same time other artists were developing naturalism. In the former area, the style is too cold and impersonal for me. In the latter group, Simon Vouet's Study of a Woman Seated on a Step has an informality that appeals to modern tastes. However, the presence of a study of hand on the same piece of paper reveals that it was only meant as a preparatory piece. Perhaps the most appealing of the drawings in the exhibition are the portraits. Vout's portrait of his patron Louis XIII presents the sitter as an affable human being rather than a remote monarch. In contrast, Daniel Dumononstier's Portriat of A Gentleman of the French Court is technically excellent but the sitter comes across as quite cold. One thing that surpised me was the color of the drawings. Inasmuch as the works are nearly four centuries old, one might well expect yellowed paper and faded ink. However, quite a few of the works were done on light brown paper and used brown ink. Thus, they probably looked much the same four centuries ago as they do today. The exhibition includes more than 50 drawings. Most of these are from the Morgan's own collection but they have been supplemented with works from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and from private collections. The placards next to the various pieces are excellent. In addition, there is a complimentary booklet discussing the works. I feel this is particularly important because for the general public, this is not a particularly familiar period of French art and the information provided by the Morgan explains its significance. This makes it a more enjoyable as well as educational experience. “Eighteenth Century Pastel Portraits” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small exhibit of European pastels. It includes, French, Italian, German and British works from the museum's collection.

An exhibition of pastels is not all that common. Works done in pastel are light sensitive. Prolonged exposure to light causes some pigments to fade. In addition, most pastels are done on paper and paper can fade or deteriorate with prolonged exposure to light. As a result, museums generally exhibit pastels in rooms with dim light and even then only for brief periods. The difficulties associated with such arrangements prevent museums from mounting pastel exhibitions very often. Essentially, a pastel is made up of pigment and a binder such as gum. The combination is then molded into a rounded or squared stick. The artist can then use the sticks in the same manner as a pencil. In other words, he or she can create a work without using brushes or mediums such as oils. Historically, pastels were often referred to as crayons. However, pastels differ from modern crayons in that the binder in crayons is usually wax. Pastels are more powdery than modern crayons. While crayons stick to paper better than pastels, pastels are easier to blend and they cover the ground more easily than crayons. Another somewhat confusing term that you often see is “pastel painting.” A pastel painting merely means that the pastels cover the entire ground. A pastel that leaves part of the paper exposed is a “pastel sketch.” It is believed that pastels were invented in the 15th century. There is evidence that Leonardo Da Vinci knew of pastels from a French artist in 1499. In any event, pastel portraits became very popular in Europe during the 18th century. People were attracted by the luminosity of the pastels and the speed and ease with which they could be used. The exhibit presents works by several of the leading pastelists of that era. Rosalba Carriera specalized in pastel portraits and became one of the most successful women artists of all time. She began by painting miniatures but by 1703, she had mastered pastels. Not long after, merchants, nobles and visitors to Venice were queuing for her pastel portraits. She went to Paris and painted the king and his nobles. She went to Vienna and the Holy Roman Emperor became her patron. Carriera is represented by a portrait of a young Irishman dressed in a cloak and tricorne hat. The mask that he has shifted away from his face shows that he is in Venice for the Carnival. Proud and dashing, it is the image of a young noble living life to the full in that romantic city. John Russell was the leading English pastel portraitist. In fact, he was appointed pastel artists to King George III. He also wrote the still inflential book Elements of Painting with Crayons. Russell is represented by three works. One is a charming portrait of his daughter with a baby. The other two are commission portraits of a merchant and his wife. She looks like the dominate one of the couple while he seems to have the look of someone who knows when he is well off. The signs by the paintings tell us that she was an heiress and that when the couple married, he took her family name. Adelaide Labille-Guiard was a member of the French royal academy of painting and sculpture. She is represented by a portrait of Elisabeth de France, the younger sister of King Louis XVI. A virtuous and religious person, there have been calls for pleasant looking person's beatification. However, there is always an element of tragedy in pictures of the members of this doomed family. The images in this exhibit are in sharp contrast to the familiar pastels of artists such as Degas. Rather than strong expressive lines, these works are soft and smooth with no trace of the artists' strokes. Still, they subtlety convey the personalities of the sitters. “Frederic Remington at the Met” is a small, introductory exhibit presenting some 20 paintings, sculptures, works on paper and illustrated books relating to Remington. Although famous for his depictions of the Old West, the artist lived during much of his life in the New York City area. It is known that he came to the Metropolitan Museum (the "Met") to study works. In addition, several of his works came into the Met's collection during Remington's lifetime.

Frederic Remington was born in upstate New York. His father, who was a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War, hoped that his son would follow a career in the military. However, when Frederic entered Yale in 1878, he choose to study art. More interested in playing football than studying, he left Yale after only three semesters. With the idea of investing the inheritance he received after his father's death in a mine or a ranch, Frederic set out for Montana in 1881. Although his investment plans did not pan out, it was an experience that would shape the rest of his life. Remington was captivated by the spirit of the Old West and sketched the cowboys, soldiers and Native Americans that he encountered. He would return to the West again and again throughout his career as a source of inspiration. Remington sold his first sketch to Harpers Weekly in 1882. This was the beginning of a successful career as an illustrator. In addition to numerous magazines, Remington would go on to illustrate books by Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister as well as Remington's own novels. Returning east, he moved to Brooklyn and to build his artistic skills enrolled for three months at the Art Students League of New York. He also studied works on display at the Metropolitan Museum, particularly those of the French academic painters. The exhibit gives a glimpse of Remington's work as an illustrator. There are examples of published works as well as one of his preliminary sketches made on the scene for a work that would be completed in the studio. However, the most interesting of these works are monochrome oil paintings. At first glance, these appear to be black and white photos of paintings. However, you quickly see that they are the original paintings. They were done in black and white to facilitate their reproduction in the magazines of the day. Remington was not satisfied with being an illustrator. At that time, illustration was considered a lesser form of art or, in some circles, not really art at all. In illustration, it was argued, the objective is to support the written words, the concept and inspiration thus coming from the writer rather than the mind of the illustrator. Moreover, illustration was viewed as too commonplace and too commercial. To achieve recognition as a serious artist, Remington began exhibiting paintings in 1887 and had his first solo exhibition in 1893. Although his works were popular, he remained somewhat dissatisfied and later in his life he burnt many of his early works. A highpoint of the exhibit is Remington's painting “On the Southern Plains.” One of Remington's later works, its color and style reflect the artist's movement away from French academic painting toward a more impressionistic style. It shows a group of cavalry soldiers, guns drawn riding to meet some unseen foe. They are not formed in a battle line like cavalry soldiers preparing to attack did in those days. Rather, they ride as a group of individuals - - very American. As throughout Remington's works, the people depicted are noble and engaged in a worthy pursuit. Whether that is a historically accurate portrayal of the Old West is irrelevant. Like a John Ford movie, it has a romantic, heroic appeal and that is good for the soul. In 1895, the sculptor Frederick Ruckstull taught Remington how to do sculpture. Remington went on to create some 22 different bronzes. The exhibit has several of them on display including his first statue, “The Bronco Buster.” Remington's statues are small rather than monumental. There are no busts of famous men. Rather, the statues are of the common people of the Old West. While the artists of the Hudson River School and other artists who depicted the frontier were interested in its wondrous landscapes, Remington was interested in people. And the bronzes depict people in action - - whether it is a cowboy on a bronco, a mountain man going down a steep slope or a Cheyenne warrior speeding along on a horse, there is motion in these statues. Tragically, Remington died at the age of 49 due to complications arsing from an appendectomy In those days, it was the fashion for successful men to overeat. As a result, the once lean athlete was some 300 pounds when he died. Moreover, health problems brought on by his weight prevented him from working outside the studio towards the end of his life - - something he very much desired to do as he became interested in the work of the Impressionists. “Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York is the first 21st century retrospective of Robert Rauschenberg's work. Extending over several rooms, it is a well-organized survey of the artist's career.

Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, Texas and was initially going to be a pharmacist. However, World War II intervened and he was drafted into the United States Navy where he worked as a technician in a mental hospital. Following the war, he shifted his focus to art and studied at the Kansas City Art Institute, the Academie Julian in Paris and at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. He also studied at the Art Students League in New York City. The League was a center of creativity in the late 1940s with a good camaraderie among the students. To illustrate, my mother (see Art by Valda) also studied there at that time. Some 20 odd years later, I recall her mentioning that she had just spoken to Rauschenberg on the telephone about some artistic problem that she was trying to solve. This took place even though they now inhabited different worlds and their approaches to art were quite different. In the 1950s, Rauschenberg established himself as a successful artist and by the 1960s, he was already having one-man retrospective shows. His influential work was described as Neo-dada and he is credited with being a forerunner of the Pop Art movement. The exhibit at MOMA contains some 250 works including some of his best known works such as “Bed”, “Canyon” and “Monogram.” As can be expected from MOMA, the works are displayed to advantage with a substantial amount of supporting information both posted near the works and on MOMA's free app. The challenge in presenting a retrospective of an artists of the stature of Rauschenburg is to do so in a way that enables the viewer to draw conclusions about the artist and his works. The first lesson I learned from this exhibition was that Rauschenberg's work was evolutionary. In general, the exhibit presents Rauschenburg's work chronologically. The works that one encounters at the beginning of the exhibit are much different than the works at the other end. Rauschenberg continued to grow throughout his career. I was also impressed by his innovation. Rauschenberg sought to erase the boundaries between art and everyday life. Indeed, he is well-known for employing non-traditional materials and found objects in his works. This broadened the avenues for artistic expression. It also provoked viewers to think in new ways about the world around them. Rauschenberg sought to provoke thought. Critics and academics attribute various meanings to his works. However, Rauschenberg declined to reveal their “true meaning.” His belief was that the meaning was in the control of the viewer. The work only created paths for dialogue. The viewer's thought process could change depending upon when he or she was viewing the work and what was happening in his or her life. Consequently, a work can have many meanings, all of which are valid. We also see that creating art does not have to be a solitary pursuit. From his early work with his wife, the painter Susan Well, Rauschenberg collaborated with other artists. This includes people from the world of music and dance such as John Cage and Merce Cunningham as well as scientists who brought knowledge of technology to the effort. For the most part, Rauschenberg's works are not aesthetically pleasing. You do not come away from one of his works thinking that it would look great in your living room. Like many intellectuals of his time, Rauschenberg resisted the idea that art should be pretty. As a result, he was uncomfortable with some of the pieces he created in the 1970s employing hand-spun silk fabrics that he found on a trip to India. They are by far the most eye pleasing works in the exhibit. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed