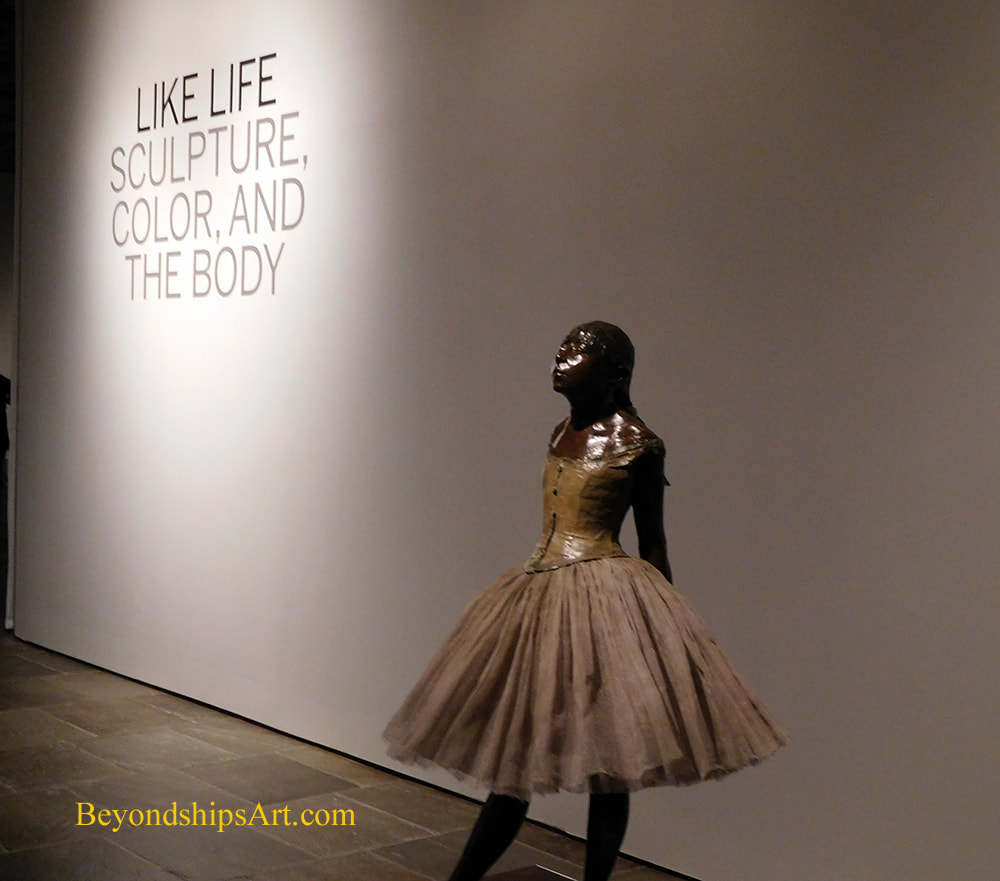

Ocean liners have earned a place in history. During the era of ocean liner travel, these ships transported millions of immigrants from Europe to North America and Australia, they provided a transportation link between the nations of the world, carried troops, acted as hospitals during times of war and were at the forefront of technology. Thus, one might well expect to find an exhibition about ocean liners at a history museum. But what do ocean liners have to do with art? “Ocean Liners: Speed and Style” at London's Victoria and Albert Museum explores this question with 250 objects, including paintings, sculpture, and ship models, alongside objects from shipyards, wall panels, furniture, fashion, textiles, photographs, posters and film. Beginning with Brunel’s steamship, the Great Eastern of 1859, the exhibition traces the design stories behind some of the world’s most luxurious liners including the Beaux-Arts interiors of Kronprinz Wilhelm, Titanic and its sister ship, Olympic; the floating Art Deco palaces of Queen Mary and Normandie; and the streamlined Modernism of SS United States and QE2. The answer to the above-stated question is that ocean liners intersected with art in quite a few ways. First, ocean liners intersected with art as architecture. Beginning in the early 20th century, ocean liners grew from being mere vehicles for transportation into environments in which thousands of people lived. Streamlined, they took on lines which influenced architecture both at sea and on land. Similarly, they also influenced the engineering design of the day. Just as a great building is art, so is a great ship. Second, there is interior design. In order to attract passengers, particularly, well-to-do passengers, the ocean liners developed luxurious interiors. At first, the shipping lines sought to imitate the grand hotels ashore but over time they created their own styles. Furthermore, as ocean liners became symbols of national pride, they were filled with artistic treasures. Art Deco works from the 1930s French liner Normandie can now be found in major museums such as the Metropolitan Museum. Similarly, the interiors of Cunard Line's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth showcased works from around the British Empire. The examples of ocean liner furniture and paneling included in the exhibition demonstrate the quality of this decoration. Along the same lines, the shipping lines did not just rely on word-of-mouth to attract customers. In order to lure passengers aboard, they created posters and brochures advertising the ships. Whereas today's advertising relies primarily on glossy photographs, these advertisements often involved drawings and other artistic depictions of the ships and life at sea. In addition, the graphic layouts were often artistic. The ocean liners also influenced fashion. During the Golden Age of Ocean Liner travel, people dressed while at sea. Elegant gowns, dinner suits, blazers and day wear were necessities for a first class voyage. Passengers displayed the latest designs and designers were inspired to create new designs. Examples of fashions worn aboard ship are included in the exhibition such as a Christian Dior suit worn by Marlene Dietrich as she arrived in New York aboard the Queen Mary in 1950 and a striking Lucien Lelong couture gown worn for the maiden voyage of Normandie in 1935. At the same time, artists were inspired to create works featuring ocean liners. These included not just traditional maritime paintings of ships but also abstract works. Several Cubist-style works are included in the exhibition. Filmmakers were also inspired by the ocean liner image. The exhibition presents clips from a number of major motion pictures that were either about or set on ocean liners. Overall, the exhibition provides a good introduction to ocean liners and their artistic significance. Along the way, it introduces the major ships and it tells their story. The lighting and use of technology also enhance the exhibition.  “Leon Golub Raw Nerve” at the Met Breuer in New York City is a selective survey of the work of the 20th century American artist Leon Golub. Born in Chicago in 1922, Golub studied art history at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1942. After the Second World War, he studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. There he met his wife, the artist Nancy Spero, to whom he was married for nearly 50 years. The two arists lived in Europe for periods during the 1950s and 1960s. While there, Golub developed his interest in 19th century historical painting and artists such as Jacques Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He was also interested in ancient Greek and Roman art. As a result, at a time when the art establishment was only interested in abstraction, Golub was creating art in which recognizable human figures were central. Golub, however, was not a conventional artist. While the influences of ancient and traditional art can be seen in his works, he also incorporated much of the force of the abstract expressionist painters. His images were often done with free broad strokes. He added layers of paint and then scraped them away. He left sections of the canvas in its raw state. This technique did not make for pretty pictures but it did make them emotionally powerful. When Golub and Spero returned to the United States in the 1960s, opposition to the Vietnam War was growing as that conflict escalated. Golub became involved in the anti-war movement and violence and cruelty became themes in his art. Other social and political issues such as racial inequality, torture, oppression and political corruption would also draw Golub's attention throughout the rest of his career. An artist seeking to convey a political or social message with a work of art has to be careful to avoid making the work dependent upon the viewer's knowledge of the underlying political or social issue. A scene or a symbol that everyone today would recognize as having a certain meaning may not mean anything to a viewer 20 years from now. Thus, a work that is too heavily dependent upon today's headlines may have no meaning in the future. Golub's works transcend the headlines. For example, “Gigantomachy II' is a monumental painting of a group of muscular male figures fighting, which was done during the Vietnam War. The title refers to a battle between the Olympian gods and a race of giants and the painting recalls an ancient Greek frieze. However, it is not a glorious depiction of battle but rather conveys a sense of cruelty and pain. Thus, it is not just about ending the Vietnam War but is a condemnation of war that continues to have meaning. Along the same lines, in “Two Black Women and a White Man,” Golub presents two black women sitting on a bench with a white man leaning against a wall behind them. Perhaps, it is a group waiting for a bus. However, the positioning of the figures and the way they are avoiding any interaction, underscores the separation and isolation of the races. The scene could be in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement or in South Africa during Apartheid, it could be now. The message of the picture still comes through. “Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)” at the Met Breuer in New York City surveys 700 years of Western sculpture focusing on works that in one way or another attempt to approximate life. The works occupy two floors of the museum and are drawn from the Met's own collection as well as works on loan from elsewhere.

Western sculpture has long depicted the human form. However, at least since Medieval times, the majority of the sculptures of the human body have not tried to convey a life-like appearance. To illustrate, marble statues in museums are usually left white and bronze statues in the park are usually the color of the metal. They are meant as depictions of the human form rather than attempts to re-create a real person. No one would mistake these statues for real people. Throughout this period, however, there have been attempts to cross the border line traditionally observed by sculptors. Most often this has been done by painting the sculpture to give it the color of a real person. However, it has also been done by incorporating elements such as human hair in the sculpture or by dressing the sculpture in clothing. Plastics and similar materials have made it easier to approach a life-like look. This exhibition looks at the various ways sculptors have striven to create a life-like image. There are examples of religious sculptures painted to make the saint or other subject appear alive. A life-like appearance was thought by some to be helpful in persuading viewers to believe. Others, however, condemned such depictions as being akin to idolatry as people might worship the statue rather than the concept behind the statue. Edgar Degas clothed his famous sculpture of a young ballet dancer with an actual ballet costume. While the image is now very familiar, it was unsettling to 19th century viewers when it was first shown in Paris. Sculptures did not wear actual clothing. More recently, artists have not only clothed figures but by using technology and artificial materials have created figures so life-like that the viewer is left wondering whether the figure is really just someone standing still. Beyond the novelty of such statues, they can be used to capture a moment in time when surrounded by furniture or other props.. Traditionally, statues remained in one pose. Mannequins and other figures with movable parts generally were not considered art. However, the exhibition shows that artists have in the past and now have used movable parts in their sculpture. The exhibition does not present the works chronologically but rather by theme. For example, one gallery is devoted to the Pygmalion myth, in which the gods grant a sculptor's wish that the statue that he has created turn into a real woman. The works include a 19th century painting, a series of drawings by Pablo Picasso and John De Andrea's 1980 sculptural scene in which figures made of polyvinyl polychromed in oil depict the artist and his sculpture with life-like detail. “Life-like” is a phrase often used at funerals to describe the mortician's treatment of the corpse. Regardless of how closely a sculpture approximates life, the fact remains that it is not alive. Thus, there is a morbid element to this line of sculpture. In fact, one of the works is a corpse. The 19th century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham specified in his will that after his death his body would be dissected. After that was done, the body was to be preserved and brought out at meetings at the University of London His wishes were followed. Over the years, the head deteriorated and so a wax head was mounted on the body. The clothed body with its wax head is seated in a glass case. The smile indicates that Bentham would have enjoyed the viewers' discomfort. Along the same lines, there are sculptures with blood and/or vital organs showing. The fact that the sculptures are life-like makes these mutilations rather grisly even though no real person was involved. Although sometimes unsettling, overall, this is an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition. The exhibition shows that an inanimate object can be made to appear strikingly like a real person. Yet, oddly enough, in art, the essence of a person often comes through better in a less realistic image. Thus, one is left to ponder what it is that sets a living being apart.  "The Long Run” at New York's Museum of Modern Art is an exhibition encompassing works by nearly 50 artists who were active in modern art during the second half of the 20th century. The artists include numerous famous names such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichenstein, Andy Warhol and Georgia O'Keefe. The works exhibited are examples of work done later in these artists' careers. Rejecting the notion that innovation in art is “a singular event—a bolt of lightning that strikes once and forever changes what follows,” the exhibit seeks to show that “invention results from sustained critical thinking, persistent observation, and countless hours in the studio.” The exhibit seeks to illustrate its thesis by presenting works that show the evolution of the artists' works past the time when they were first recognized. One cannot seriously debate the exhibit's thesis. The notion of an artist being struck with a bolt from the blue that leads to a new direction in art is more the stuff of Hollywood drams than reality. As in other siciplines, artists develop their thoughts over time. Skills are refined and new materials are encountered that enable the artist to do new and/or different things, At the same time, personal relationships may be changing, new associations formed and events in the outside world may occur that influence the artist's thinking. Not only is there an evolutionary trail leading up to an artistic breakthrough but there is a trail after that breakthrough. The exhibit shows that artists evolve in different ways. Some artists make radical changes in style. For example, in 1969, Phillip Guston abandoned the abstract style that he had been known for in favor of a more figurative style. He said that he needed to make this change in order to enable him to address the political and social issues of the day. Other artists continue on in the same vein that first brought them recognition. For example, Andy Warhol's black and white drawing of Da Vinci's Last Supper with various colored consumer product logos superimposed makes essentially the same point as his earlier paintings of Campbell's Soup cans, i.e., the commercialization of western society. Along the same lines, Roy Lichenstein's “Interior with Mobile” is similar in style to his earlier comic strip inspired works. Even for those artists who stayed close to their original style, the exhibit makes the point that these artists went on working throughout their lives. In some cases, the later works may not have be as important to the history of art as their earlier works but these artists continued to produce vibrant and worthwhile art. Leaving aside the thesis of the exhibit, the Long Run is still an enjoyable exhibit. It brings together numerous examples of good modern art. This includes lesser known examples by major artists that deserve to be brought to the public's attention. “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” at the Museum of Modern Art presents the work of the artist who led the development of the modernist movement in Brazil. During the 1920s, Tarsila, as she is widely known in Brazil, developed a distinctive style that was truly Brazilian. MOMA has assembled over 100 works drawn from various collections including some of her landmark paintings to document this development.

Tarsila was born in Capivari, a small town near Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1886. Her family owned coffee plantations. Although it was unusual at that time for girls from affluent families to pursue higher education, Tarsilia was allowed to pursue her interest in art, both in Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain. Her instructors were conservative, academic artists. In 1920, after the end of her first marriage, Tarsila went to Paris in 1920 to study at the prestigious Academie Julian. Her studies were again in the academic tradition. Meanwhile, a modern art movement had taken root in Brazil. The landmark Semana de Arte Moderna was a festival that called for an end to academic art. Upon Tarsila's return to Brazil, she discovered modern art became a leader in this movement, one of the five artists and writers in the Grupo dos Cincos. In 1922, she returned to Paris and studied with several Cubist artists including Ferdinand Leger and Andre Lehote. However, she continued to think in terms of Brazil. She painted “A Negra,” an abstract portrait of an Afro-Brazilian woman. Returning to Brazil, she embarked upon a tour around the country. The drawings of the countryside and everyday life she made while on this journey served as inspiration for later paintings. Her traveling companion was the writer Oswald de Andrade wrote a manifesto “Pau-Brasil” calling for truly Brazilian culture. She married Andrade in 1926. Tarsila made another journey to Paris in 1928 where she came into contact with surrealist art. (It should be noted that Tarsila did not live like a starving artist in Paris. A renown beauty from a wealthy family, she lived a lavish lifestyle, mixing with famous personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals). That same year, she painted “Abaporu” (the man who eats human flesh) as a birthday present for her husband. He used the image for the cover of his “Manifesto of Anthropology,” which called upon artists to cannibalize European culture and other influences in order to create a distinctive Brazilian culture. The painting and the manifesto are considered landmarks in the development of Brazilian culture. Tarsila's family fortune was all but lost as a result of The New York Stock Exchange crash of 1929 and the following Depression. Her marriage to Andrade ended the following year. In 1931, Tarsila traveled to Moscow with her new boyfriend, a communist doctor. There she was influenced by Socialist Realism. Her subsequent work was primarily concerned with social issues. The exhibition at MOMA focuses on the decade beginning with her journey to Paris in 1920. It demonstrates how Tarsila's work evolved incorporating over time elements of Cubism, Brazilian folk art and Surrealism while retaining her own style. Although she was influenced by each of these schools, she did not become part of them. Hers is a distinctive style: flat two dimensional; populated with simplified, distorted figures and landscapes; often with geometric backgrounds. It is also clearly Brazilian, not only in the choice of subject matter but in the selection of colors. In short, it is what Andrade was calling for - - a synthesis of a number of influences producing a truly Brazilian art. The exhibit also includes some works after her trip to Russia. “The Workers” (1933) was one of the first paintings in Brazil dealing with social issues. It reflects the influence of Soviet painting both in subject matter and palette. Incorporation of this soulless style was not a happy addition to Tarsila's arsenal. The work does not have the life of her earlier works and the treatment of the subject matter is much like what numerous other artists were doing at the time. However, it does serve to spotlight how special her work was during the preceding decade. “Within Genres” at the Perez Art Museum Miami relates works from the museum's permanent collection to the categorizes (genres) into which European art was divided from the Renaissance into the 19th century. Inasmuch as the museum's permanent collection focuses on modern and contemporary art, it relates recent art to these traditional categories.

In their heyday, the traditional genres were used not just to group and categorize works of art but as a hierarchy. For example, history painting was considered a higher form of artistic endeavor than still life painting or landscapes. The museum asserts that this hierarchy “was challenged in the 19th century with the development of modernism and the avant garde.” Actually, the genre hierarchy was challenged earlier in the 19th century by the Impressionists and by artists such as JMW Turner but in any case, the old academic hierarchy is no longer recognized today. While the hierarchy no longer exists, art is still influenced by the traditional genres. In six exhibit rooms, the museum uses works from its permanent collection to illustrate that recent art can still be related to the traditional categories: Still Life; Landscapes; Scenes of Everyday Life; Portraiture and History Painting. We see that 20th and 21st century artists are still producing works that can be categorized as still lifes, landscapes, scenes of everyday life, portraits and works relating to history. In addition, we see that their approach of these different categories covers a wide range from the traditional to abstraction to concept pieces. The materials used range from traditional oil on canvas to video and installations. While the concept of the exhibit is clearly valid, the exhibit is let down by the small number of works used to illustrate each genre. Contemporary art's roots into the past are more numerous and diverse than the examples show. For example, with the exception of Domingo Ramos' masterful “Landscape with Palm Trees.” (1936) realism during the 20th century is essentially unrepresented. Moreover, the recent move toward realism in contemporary art is all but ignored despite its relation to the art of the past. Still, there are a number of gems in the exhibit. As the museum's signs note, Diego Rivera's “Naturaleza muerta” is a beautiful still life in the tradition of Cezanne. Along the same lines, the signs point out that Roy Lichenstein's abstract silk screen “Water lilies with willows” has roots extending to Monet. Of course, neither Cezanne nor Monet was a traditional academic painter but that just shows that earlier artistic rebels were also influenced by the traditional genres. Like more recent artists, they took their own approach to these genres. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed