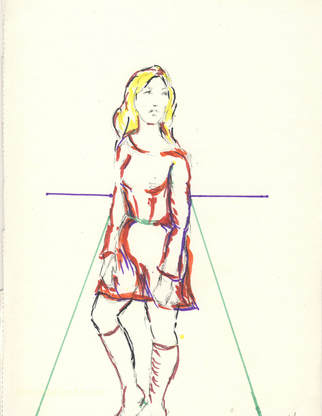

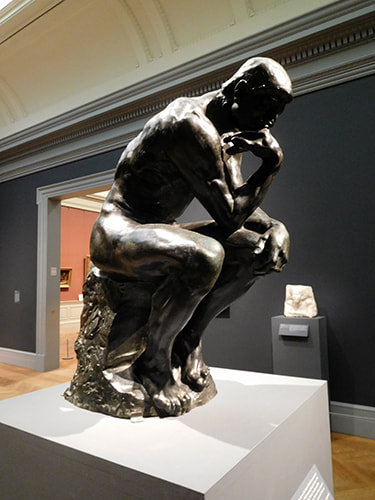

Several people have asked me to explain what I mean by “essential line drawing” as used on this website and in various postings that I have made on social media. Essential line drawing is a term that I use to describe a type of drawing that I have been doing for many years now. I doubt that it is in any art dictionary but it is a handy way of describing this type of drawing. Distilled to its essence, essential line drawing seeks to produce an image with the minimum number of lines that are needed to convey the concept that the artist is trying to express. For example, in a portrait, the image would be the minimum number of lines needed to convey the essence of the sitter. In a scene, it could be to the lines needed to express the emotions of the moment. This is not meant to be an academic exercise. The objectives are simplicity and clarity. You are putting aside what is non-essential in order to allow that is essential to show through more clearly. There are examples of essential line drawing in the works of many famous artists. Papblo Picasso and Henri Matisse did essential line drawings. More recently, you can find examples in the works of Peter Max. Each of these artists had their own approach but the basic concept is the same. The end result often sits on the border between realism and abstraction. You can tell what the image is but it is far from being a photographic image. From a techncal perspective, the biggest difficulty often is doing too much. If you put in too many lines, it becomes a standard line drawing. More importantly, they obscure the concept. Again, the objectives are simplicity and clarity. This is not to say that the essential line approach is the only way to produce art. It is simply one approach that I use. There are examples of essential line portraits and essential line figure drawings on Beyondships Art.  Rodin At The Met is a salute to the sculptor Auguste Rodin on the 100th anniversary of his death. It is an entirely fitting tribute as the then-young museum was a supporter of this artist during his lifetime to the extent of opening a gallery dedicated to his work in 1912. Rodin showed his appreciation by giving the Met additional works. This exhibit of some 50 works includes not only the works that the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired during the artist's lifetime but also works that it has collected subsequently. Auguste Rodin was from a working class family that lived in Paris. He received his basic training in art at the Petit Ecole. However, he was refused admission to the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the leading art academy in France. Although this forced Rodin onto a much more difficult road to success, he also avoided indoctrination into the lifeless Neo-classical style that was the trademark of that school. Instead, Rodin slowly built his own style along with his reputation, first as an apprentice to other artists and then on his own. One turning point was his visit to Italy in 1876 during which he was very impressed by the sculptures of Michelangelo. Even after he achieved fame, Rodin's style was not what people expected. There is story after story of how individuals and public authorities commissioned works only to be shocked by Rodin's final product. Those that were rejected are now recognized as some of the greatest works of 19th century art. Rodin found fame in the United States after some of his works were displayed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. Here again, some of his works were found so shocking that they were exhibited behind a curtain in an area that required special permission to enter. However, private collectors and museums were soon purchasing his works. The Met has casts of several of Rodin's best known pieces including The Thinker, the companion sculptures Adam and Eve, the Age of Bronze and a study for the Monument to Balzac. Rodin modeled his sculptures in clay. Plaster casts were then made to preserve the sculpture. From these, bronze casts were made or marble carved often by studio assistants. This explains why the same work can appear in multiple museums. There is a discernible difference between Rodin's bronzes and marbles. You can see the power of the sculptor's fingers working the underlying clay in the bronzes. The marbles tend to be less distinct, smoother and gauzier, almost dream-like. In either case, you can clearly see Rodin's works were a clear break from the allegorical figures and gods and goddess so popular at the time. While some have titles that relate back to mythology or the bible, these works are of real people with real emotion. A particularly fascinating part of this exhibit is Rodin's works on paper. In addition to sculpture, Rodin also did watercolors and drawings. Some of these were in preparation for sculptures but mostly they were another means of communication. It is said that Rodin would draw without removing the pen from the paper and without taking his eyes off the model. The results were images that border on abstraction and which are full of emotion. Along with Rodin's works, the Met has hung examples of works done by his friends. One such friend was Claude Monet who also was leading a revolution in art in 19th century France. The two artists held a joint exhibition in 1889. These contemporary works help to place Rodin's works in context  In my view, this exhibition is mislabeled. The title “Gilded Age Drawings at the Met” suggests a collection of black and white sketches of hefty figures supposed to be gods and goddesses from Greek mythology or other syrupy themes that were popular in the late Victorian age. In reality, this exhibit is a delightful small group of colorful watercolors and pastels done by artists whose work has transcended their time. Included in this exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art are several watercolors by John Singer Sargent. Sargent was one of the most successful portrait painters of his day. However, he also did watercolors. These were not intended for public display but rather were for his own benefit. As a result, they are done in a very loose style using a palette reflecting the fact that he also spent time working with Monet and the Impressionism. Most of the Sargent watercolors are landscapes or other Impressionistic scenes. However, there is also a small watercolor done during World War I when he visited the front lines as a war artist. It is of two men suffering from the effects of mustard gas and is a very powerful piece. Thomas Eakins is also represented. Unlike Sargent, Eakins exhibited his watercolors and they bear a close resemblance to the style he used in his oil paintings. These are illustration-like scenes from everyday life including the controversial “Dancing Lesson.” Is it a sympathetic illustration of black life shortly after emancipation or is it meant as a comedy that re-enforces racial stereotypes? The signage appears to conclude the former noting that it won a silver medal when it was exhibited in Boston in the 1870s. There are also several watercolors by Winslow Homer. These capture the various moods and energy of the sea in a variety of scenes. Homer manipulated the watercolors to produce amazing sea and sky effects. James McNeill Whistler was also a successful Victorian era artist. However, his style looked more toward the future than the art establishment of the day. “His Lady in Grey” is a tiny watercolor that is similar in concept to some his full-length female portraits. I sometimes come across comments on social media about whether a watercolor should be just translucent paint. However, in almost all of these works, the masters used gouache (opaque watercolor) along with the translucent watercolors. Not all the works in this exhibit are watercolors. There are also two pastels by Mary Cassat. One is a large, yet tender, finished work that returns to her favorite theme - - the relationship between a mother and her child. The other work is more of a sketch on colored paper showing a woman on a bench knitting. There is a great deal of energy in the Impressionist master's short, seemingly rapid, strokes. There are also works by artists who are less well-known to the general public. Jane Peterson's scene of a New York City street during the patriotic parades around World War I complements Childe Hassan's popular paintings of those days. Charles Ethan Porter, an African American artists who specialized in still lifes is also represented. John LaFarge did not try to capture the image of flowers with absolute realism but rather sought to capture their essence thus foreshadowing the century which followed. Also on display are some artist boxes from the late 19th century. What is surprising is that the pans and tubes of watercolor paint and the brushes do not look much different than those of today.  Major exhibitions of drawings seem to be proliferating. In recent weeks, I have reviewed such exhibits at the Morgan Library and Museum, the National Portrait Gallery in London and now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This attention is well-deserved because as the Met correctly says “drawing is the foundation of all the visual arts.” “Leonardo to Matisse” is a survey of European art from the Renaissance to the 20th century. It is done through works from such masters as Leonardo, Rembrandt, Duerer, Tiepolo, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Matisse. Moreover, because it is done utilizing works from the collection of one person, viewing the exhibit is a conversation with one connoisseur about art. The works on exhibit are from the Met's Robert Lehman Collection. Robert Lehman graduated from Yale University in 1913 and by 1925 he was the head of the family-business, the investment banking house Lehman Brothers. He expanded that firm, bringing in outside partners, and made it into a financial powerhouse. Mr. Lehman's interest in art began at an early age. His father and mother collected art and by the time Robert was a teenager, he had begun collecting on his own. Over the years, he accumulated a massive collection focusing on European Art from the 14th to the 20th century. By 1962, it had become so massive that he used the townhouse that he grew up on New York's West 54th Street solely as a repository for his collection. It was not just a large collection but an important collection. Parts of it had been exhibited by the Louvre in Paris, the first private American collection to be so honored. Lehman took advice from experts in making his purchases but he also simply purchased what he liked. Following Lehman's death in 1969, the Robert Lehman Foundation bestowed the collection of some, 2,600 works to the Metropolitan, where Mr. Lehman had been a trustee and chairman of the board. A new wing was constructed to exhibit the collection in order to follow his stipulation that the works be exhibited together as a collection. There were more than 750 drawings in the collection. This exhibit presents some 60 works, which the Met describes as presenting “the full range of Robert Lehman's vast and distinguished drawings collection.” We can see from this exhibit that Mr. Lehman was interested in a broad span of European art. Although the signage tells us that his first interest was in Italian Renaissance drawing, the works include sheets from other times, other parts of Europe and a wide range of styles. Indeed, the works extend up to Modernism and Neo-Impressionism. Some of the works were acquired directly from living artists. Lehman also preferred finished drawings. This is not to say that all these works were finished in the sense that they were meant for public display. To the contrary, many were clearly done for the artist's own benefit in preparation for a painting or sculpture or to work out some problem of proportion or lighting etc. Indeed, Durer's self-portrait is on a sheet with a large study of a hand and Degas' dancer has other drawings on the reverse side. Rather, they are finished in the sense that the artist completed the concept. Few of the works are hasty sketches. Most of the drawings are relatively small. Consequently, they require close viewing which in turn creates an intimacy with the work. A collector would not have purchased these to decorate a large room but rather to examine from time-to-time. Very few of the drawings have color. Most are drawings done in black, brown or sometimes a combination of black, white and red chalk. Only one, a delightful tiny watercolor by Renoir, makes use of vibrant color. The exhibit is on the lower floor of the Robert Lehman Wing. Many of the paintings that Lehman collected are on display on the upper floor. While the drawings are excellent, they are overshadowed by the paintings, which include masterpieces by Ingres, Goya and Raeburn and the Impressionist masters Monet, Pissaro and Renoir. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed