|

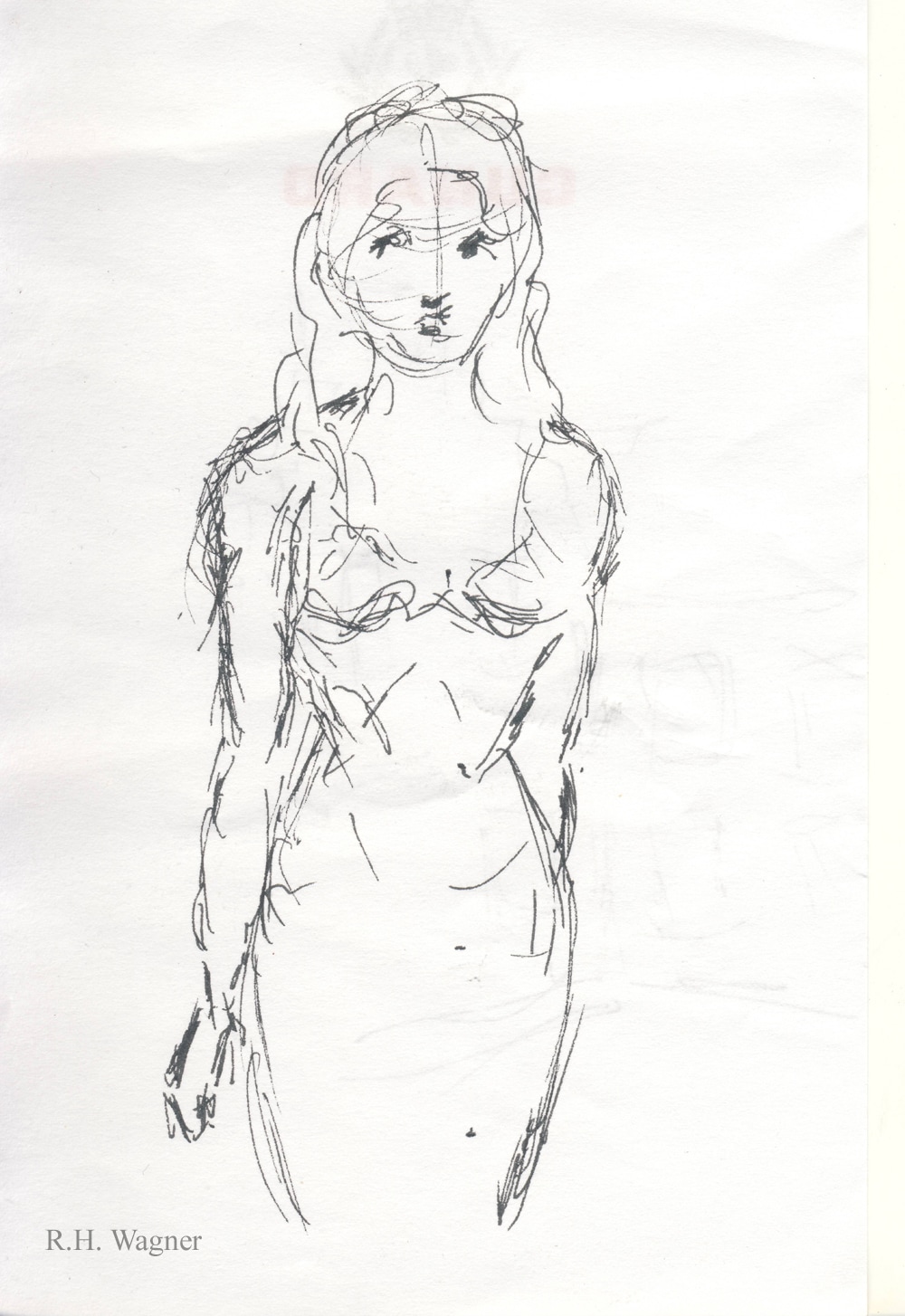

As I have mentioned before, I often do sketches while I am commuting on a train or when I am sitting waiting for something such as a doctor's appointment. For the most part, these sketches are just for practice. However, from time to time, one is a special image that I would like to take further. The problem is that the sketches are small, pocket-size images done on a note pad or on a piece of scrap paper. Their size and the quality of the paper preclude trying to make them into a series piece of art. My solution has been the traditional one - - I hand copy the image onto a larger, better quality piece of paper. Once the image has been successfully transferred, I can add color, change it or otherwise develop the work. A problem with this method is that sometimes something gets lost in making the copy. An image can have a certain something that cannot be re-captured no matter how hard you try. A random line or two may be what gives the sketch its character. Also, hand copying can be a lot of work. This week, I tried an experiment. I took two small sketches and made high-quality digital images of them. Once you make a digital image of a work, there is a lot that you can do with it using a photo editing program such as Photoshop. You can add color, erase mistakes, improve the brightness and contrast etc. But I was not looking to digitally manipulate these sketches. Rather, my goal was to enlarge the image and then work on it by hand. Therefore, the next step was to print the images. Of course, the print will depend upon the quality of the printer. However, using my rather ancient printer, I was able to print out acceptable quality prints that could serve as the base for further development. I then used a pen to emphasize some of the lines. For color, I used colored pencils on one and Cray-pas on the other. I was pleased with the results. The size of the works was now more substantial. Also, the addition of color had enhanced the images. Clearly, there are limitations to this process. The largest paper my printer will accept is A4 so the image cannot be larger than one that would fit on that size paper. Along the same lines, he printer is probably not capable of handling heavy water color paper and the like. A better printer would push these limits out further. I don't think I will give up on hand copying. However, this little experiment has put another arrow in my quiver. Before and after. On the left side are the original images, both done on 3 x 5 inch note paper. On the right, are the images after scanning, printing and further development by hand. They are now on *.5 by 11 inch paper.

On a recent visit to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (ADNS), I was introduced to the works of Maud Lewis. Maud was a talented Canadian folk artist with a compelling story. Indeed, her story is so compelling that recently a movie, “Maudie,” was made about her life. Maud Dowley was born in 1903 in rural Nova Scotia. She was born small and with hardly any chin. These difficulties were compounded when she was stricken with juvenile arthritis causing her joints to swell and deforming her hands. This condition worsened throughout her life. Most likely to avoid the taunts of other children, Maud spent most of her childhood by herself or with her immediate family. She was introduced to art by her mother who painted Christmas cards to supplement the family income. Painting became a passion for Maud. After the death of her parents, Maud lived with her brother and with her aunt for a time. But then in 1938, she married Everett Lewis, an itinerant fish peddler, who she probably met when he made a delivery to her aunt's house. She moved into Everett's tiny house near the local “poor house.” It had no electricity, no indoor plumbing and was heated only by a wood burning stove. Maud's disabilities prevented her from doing the housework so that became Everett's responsibility. Maud concentrated on her paintings. The primary vehicle for selling her art was a roadside sign saying “Paintings for Sale.” Her works were also available through a local store and Everett sold her hand-painted holiday cards from his wagon while making his deliveries of fish. The paintings were sold for a couple of dollars each. Despite the limited reach of these marketing efforts, such was the power of Maud's work that journalists began to write about her and she gradually became known for her art. This enabled her to purchase better quality materials and led to a slight improvement in lifestyle. However, Everett and she continued to live in the same rural community. Maud died in 1970. The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia has a large collection of Maud's works. Maud had no formal art training and her exposure to paintings by others was pretty much limited to what happened to be published in magazines. Thus, her works do not reflect any artistic movement or school of thought. Rather, they are flat images that have the simplicity of the early 19th century North American folk paintings. In some respects, they are similar to the works of Grandma Moses. Maud had a great sense of color and of composition. These combine to form happy images of rural life - - portraits of cats, teams of oxen, covered bridges, horse drawn sleighs, churches, rural landscapes and pictures of the sea shore. Nowhere is there a hint of the difficult life that she endured. Perhaps it would be better to say overcame rather than endured. These images reflect a triumph of the spirit over adversity. This is underscored in the centerpiece of the exhibit - - the house in which Maud and Everett lived for 30 years. After Everett's death, a private group bought the house and donated it to the Province of Nova Scotia. Following several years of conservation work, the house was re-assembled inside of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. It is indeed a tiny house. I have seen children's playhouses that were larger. As mentioned earlier, it had no modern amenities. However, there is a lot of love in this house. Maud painted not just the outside of the house but also the interior including the stove. Images of flowers speak of beauty and happiness. Inside the house, you can see some of the tools Maud used to create her art such as sardine cans that were used in mixing paint. Until she achieved some recognition, her materials were house paint, boat paint and hobby brushes. The Maud Lewis Gallery at the AGNS is thus of interest in two ways. First, there are the paintings themselves. They are pleasing images on a stand alone basis without reference to the artist's story. Second, it tells an inspirational story.  “Consequences” is a temporary exhibit at the Guernsey Museum's Greenhouse Gallery. It presents 16 paintings by Peter Le Vasseur intended to provoke change and raise awareness. Mr. Le Vasseur is a native of the Channel Islands. At a young age, his family fled the islands to escape the Nazi occupation. In the 1960s, he achieved considerable success in the London art world including several one-man shows at the Portal Gallery in Mayfair. The Beatles and several film stars are among those who purchased his works. In 1975, Mr. Le Vasseur returned to the Channel Islands and took up residence in Guernsey. The works are realistic, highly detailed, almost illustrational. The colors are bold but warm. This lulls the viewer welcoming him or her into the scene. It is only when you have gone beyond the first glance that you notice that there is something wrong with these idyliic scenes such as pollution on a beautiful beach or a fish deformed by atomic radiation cast up on a shore. All of the works in the Consequences exhibit have a message. Most deal with environmental themes. However, you also have works dealing with other issues such as isolation in modern life. Le Vasseur presents a happy scene of people enjoying a leisurely day in a public park. As you look at the vatious figures you notice that there is no interaction, everyone has earphones or is absorbed with their smart phone. There, of course, is a long tradition of using visual art to make social commentary. The works of William Hogarth in the 18th century spring to mind. In his most successful series “A Rake's Progress”, Hogarth painted a series of scenes that saturize the mores of the English upper class of that day. The problem in social commentary art is balancing the message and the artistic qualities of the work. If the message is too strong, the work often loses its artisitic appeal and becomes propaganda, the best examples being the posters created for authorian dictatorships during the 20th century. If the artistic qualities dominate, the work may fail to convey the social message that the artist was seeking to communicate. In the Consequences exhibit, Mr. Le Vasseur's works send strong messages. The scenes are colorful and attractive with the foliage and figures superbly presented. But there is always a man-made blemish to transform the happy scene into one with nightmarish implications. As a result, the viewer is left uncomfortable and forced to think about the issues presented. The question then becomes whether the message is too obvious. One could say that most people know that pollution is a bad thing. As a result of this awareness, there has been considerable progress in this area during the course of my lifetime. But environmental scentists tell us much remains to be done. Therefore, presenting a clear message reminding the public about pollution is justifiable. Inevitably, in social commentary art, the viewer's opinion of the work will be influenced by his or her opinion on the message the artist is trying to convey. But leaving politics aside, the wotrks in Consequences must be viewed as successful. First, it cannot be debated that the works are technically well done. Second, and perhaps more importantly, they do provoke the viewer to think, which was clearly the artist's intention.  When I was in Dublin, Ireland recently, I had the good fortune to see a small retrospective exhibition of the works of Margret Clarke at the National Gallery of Ireland. Margret Clarke (1884-1961) was a woman artist who achieved success as an artist in the first half of the 20th century. I mention the fact that she was a woman because in those days there was a great deal of prejudice against women and thus for a woman to have achieved success in those days is all the more impressive. Ms. Clarke began her artistic training at Newry Municipal Technical College continuing on to the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (“DMSA”). Her goal was to become an art teacher and she obtained an art teacher certificate in 1907. However, she won numerous scholarships and prizes thus enabling her to embark on a career as a professional artist. Two paintings in the exhibition by her teacher at the DMSA, Sir William Orpen, show Ms. Clarke as having an intelligent face with lively eyes. These same characteristics appear in her self-portrait. Ms. Clarke achieved success as a portrait painter and her subjects include such ntables as the future Irish prime minister Eamon de Valera. The portrait commissions are traditional and somewhat reminiscent of John Singer Sargent's portrait commissions. Her private works, which cover diverse subjects including family portraits, nude studies and genre paintings, are less conservative. You can see influences of artists such as Cezane and El Greco as well as Asian prints. Still, the works that really spoke to me were Ms. Clarke's drawings, mostly graphite on paper but also charcoal on paper. These drawings were technically superb but at the same time sensitive. Her drawing of her husband, the artist and designer Harry Clarke, done around the time of their marriage in 1914 conveys the emotion that she felt for the sitter bringing him alive. Similarly, her sketches of Julia O'Brien, who worked in the Clarke household in the 1920s have unusual sensitivity. They communicate, which to me is the hallmark of good art. Margret Clarke was only the second woman to become a full time member of the Royal Hiberian Academy in 1927. But while she achieved this degree of success during her lifetime, her reputation faded subsequently. This refelects the fact that the art establishment became co-oped by abstraction during the mid to late 20th century. Figurative work was rejected as passe and unintellectual. Such thinking has now been exposed as close-minded nonsense. Therefore, the National Gallery of Ireland's decision to spotlight the work of an artist who has undeservedly been ignored is to be applauded.  A smart phone image of a work in progress. A smart phone image of a work in progress. I find that the more I work on a picture, the less I am able to see it. No, I don't mean that my eyes become blurry. Rather, I mean that I am less able to see the picture objectively. This can lead to three problems. First, I can't see the mistakes that I have made. The eyes in a portrait can be positioned at different levels making the subject the look like something from a horror movie. Yet, what I see is something that Leonardo Da Vinci would envy. Second, I go on working even though the picture is finished. A picture can easily be ruined by overworking it. Third, I go on working on a picture even though it will never be anything worthwhile. Some pictures are just failures. There is a tendency to think, if I just make a few more changes it will be a masterpiece. However, in reality, you're just wasting your time. Better to start something new. The inability to see a work objectively occurs because the mind has a tendency to see what it wants to see. Therefore, what is needed is a fresh view of the picture. My mother, the artist Valda, used to recommend holding the picture up to a mirror. This breaks the spell and in the mirror image,you can see the work much more objectively. A technique more suited to the digital age that I often use is to take a photo of the picture with the camera in my smart phone. The objective is not to get an image that you would want to share with friends and family but rather to look at your picture in a different way. My smart phone is well-suited to this task. It takes a serviceable image in almost any light. In addition, I can see the image immediately on the phone's display screen. I often end up taking several pictures as I work. Having used the smart hone to detect a problem, I endeavor to correct the problem on the original picture. Another photo tells me whether I really have solved the problem and whether there are other problems that need correcting. The only problem that I have found with this technique is that it can use up the storage on the smart phone. Therefore, it is best to delete the images as you go along. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed