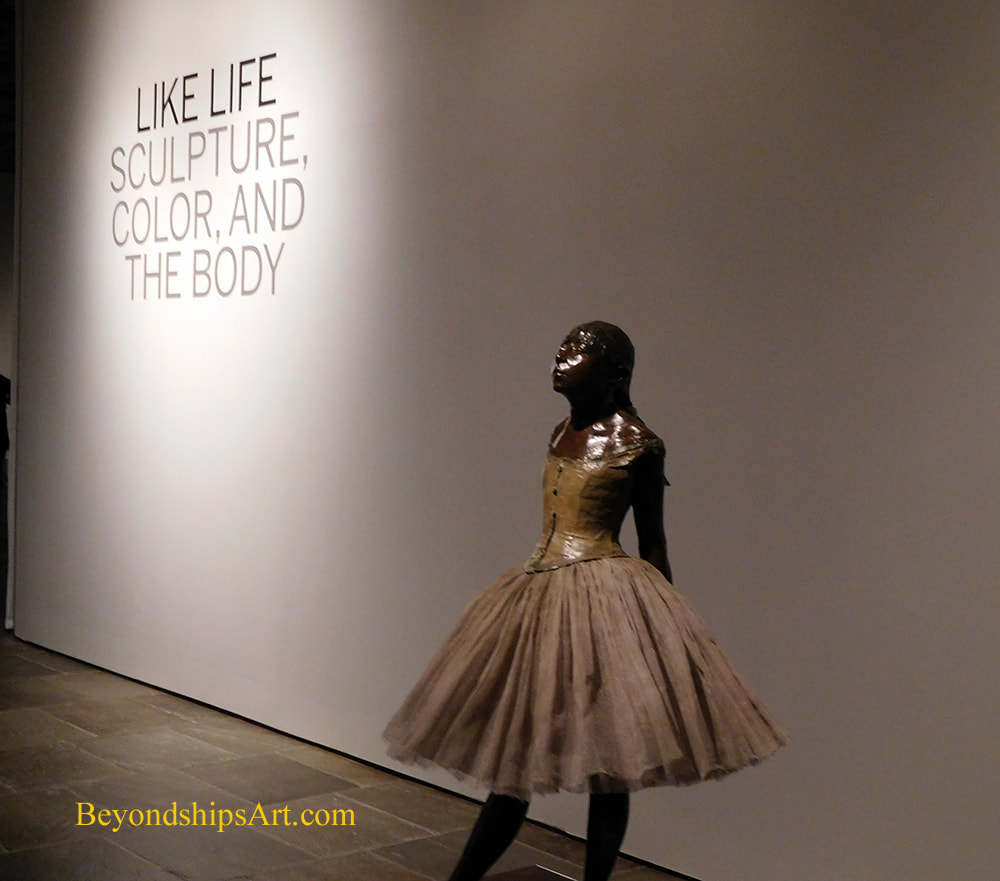

“Provocations: Anslem Kiefer at the Met Breuer” is a large exhibition drawn from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection of works by the contemporary German artist. Anslem Kiefer was born in Germany two months before the end of the Second World War in Europe. Kiefer planned from childhood to be an artist. However, when he entered the University of Freiberg, he began as a pre-law and language student. However, he soon switched to the study of art and went on to studying art at academies in Karlsruhe and Dusseldorf. He studied informally with the artist Joseph Beuys. Now a well-established artist, he lives in the South of France. Keifer's work has been primarily concerned with relating German history and culture to the present day. In particular, he has sought to confront the Nazi era. Following the end of the Second World War, the symbols of the Nazi era were outlawed in Germany. The victorious Allies were concerned that the Nazi movement could be revived if these symbols were allowed to be displayed. For many of the vanquished German people the ban made it easier to forget the horrors that had been committed in their name. However, by the 1960s, German intellectuals were arguing that the Germany had to come to terms with its past. In 1969, Kiefer came to public attention with a series of photographs that he had taken of himself in his father's Wermacht uniform giving the Nazi salute. The photos were taken with a background of historic monuments around Europe and by the seaside. Audiences wondered whether the photos were meant to be ironic or as praise for the Nazis. Kiefer's objective was to cause people to confront rather than bury the past. Kiefer has over the years expanded the scope of his work to include a broad range of German history and culture. However, since the Nazi propaganda machine conscripted much of German music, myth, legend and history, the specter of the Nazi era is never far away. Described as a Neo-expressionist, Kiefer has used a variety of mediums in his work. In addition to traditional painting and photography, his works have incorporated such things as earth, lead, straw and broken glass. He is also known for works on a monumental scale. One such monumental work displayed in the exhibition is “Bohemia Lies by the Sea” (1996). The painting has some of the force of an abstract expressionist work. However, it is actually a scene of a rutted country road extending through a field of poppies. The title is taken from an Austrian poem in which the poet longs for utopia but recognizes that it is unreachable just as landlocked Bohemia can never be by the sea. The connection to the Nazi era is that Bohemia is in the Sudetenland annexed by the Nazis just before the war. Furthermore, poppies are a symbol for lives lost in war. While Kiefer is known for his large works, I found myself drawn more to some of the smaller works in the exhibition. For example, in “Herzeleide” (Suffering heart), Keifer based his watercolor on the image in a Nazi era book of a mother looking at a document informing her that her son has been killed. Nazi propaganda exalted such sacrifices. In his painting, Kiefer has replaced the document with an artist's palette. “My Father Pledged Me A Sword” is based upon Wagner's Ring Cycle operas. In the operas, Woton, king of the gods, thrust a sword into in an ash tree. Later, his son Sigmund is in need of the sword and cries out for it. However, Kiefer has painted the sword not in a tree but in a rock atop a high cliff overlooking a fjord - - much more difficult to retrieve. Even assuming aguendo that the viewer knew nothing about German history or culture, Kiefer's art still works. The works are well composed. Sometimes bleak and sometimes harsh, they are always emotionally powerful and thought-provoking. “Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)” at the Met Breuer in New York City surveys 700 years of Western sculpture focusing on works that in one way or another attempt to approximate life. The works occupy two floors of the museum and are drawn from the Met's own collection as well as works on loan from elsewhere.

Western sculpture has long depicted the human form. However, at least since Medieval times, the majority of the sculptures of the human body have not tried to convey a life-like appearance. To illustrate, marble statues in museums are usually left white and bronze statues in the park are usually the color of the metal. They are meant as depictions of the human form rather than attempts to re-create a real person. No one would mistake these statues for real people. Throughout this period, however, there have been attempts to cross the border line traditionally observed by sculptors. Most often this has been done by painting the sculpture to give it the color of a real person. However, it has also been done by incorporating elements such as human hair in the sculpture or by dressing the sculpture in clothing. Plastics and similar materials have made it easier to approach a life-like look. This exhibition looks at the various ways sculptors have striven to create a life-like image. There are examples of religious sculptures painted to make the saint or other subject appear alive. A life-like appearance was thought by some to be helpful in persuading viewers to believe. Others, however, condemned such depictions as being akin to idolatry as people might worship the statue rather than the concept behind the statue. Edgar Degas clothed his famous sculpture of a young ballet dancer with an actual ballet costume. While the image is now very familiar, it was unsettling to 19th century viewers when it was first shown in Paris. Sculptures did not wear actual clothing. More recently, artists have not only clothed figures but by using technology and artificial materials have created figures so life-like that the viewer is left wondering whether the figure is really just someone standing still. Beyond the novelty of such statues, they can be used to capture a moment in time when surrounded by furniture or other props.. Traditionally, statues remained in one pose. Mannequins and other figures with movable parts generally were not considered art. However, the exhibition shows that artists have in the past and now have used movable parts in their sculpture. The exhibition does not present the works chronologically but rather by theme. For example, one gallery is devoted to the Pygmalion myth, in which the gods grant a sculptor's wish that the statue that he has created turn into a real woman. The works include a 19th century painting, a series of drawings by Pablo Picasso and John De Andrea's 1980 sculptural scene in which figures made of polyvinyl polychromed in oil depict the artist and his sculpture with life-like detail. “Life-like” is a phrase often used at funerals to describe the mortician's treatment of the corpse. Regardless of how closely a sculpture approximates life, the fact remains that it is not alive. Thus, there is a morbid element to this line of sculpture. In fact, one of the works is a corpse. The 19th century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham specified in his will that after his death his body would be dissected. After that was done, the body was to be preserved and brought out at meetings at the University of London His wishes were followed. Over the years, the head deteriorated and so a wax head was mounted on the body. The clothed body with its wax head is seated in a glass case. The smile indicates that Bentham would have enjoyed the viewers' discomfort. Along the same lines, there are sculptures with blood and/or vital organs showing. The fact that the sculptures are life-like makes these mutilations rather grisly even though no real person was involved. Although sometimes unsettling, overall, this is an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition. The exhibition shows that an inanimate object can be made to appear strikingly like a real person. Yet, oddly enough, in art, the essence of a person often comes through better in a less realistic image. Thus, one is left to ponder what it is that sets a living being apart.  "Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddist Painting” at the Asia Society Museum in New York City presents a selection of Tibetan paintings collected during the expeditions of Giuseppe Tucci during his expeditions to Tibet along with some of the photographs that were taken during the expedition. The paintings in the exhibit are from the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci," in Rome and are being shown for the first time in the United States. Giuseppe Tucci was a writer, scholar and explorer who made eight expeditions to Tibet during the period 1926 to 1948. Up to that time, Tibet was a remote mystery and Tibetan culture largely unknown outside of Tibet. Tucci traveled some 5,000 miles on foot and on horseback across the Tibetan plateau, In addition to meeting people and seeing places, he obtained permission to collect examples of Tibetan culture for study outside the country. In addition, Tucci brought along photographers to document the expeditions. Their mission included photographing monuments, cultural artifacts, people and their occupations. In other words, they made a systematic effort to document this ancient culture before it vanished. The exhibition presents copies of some of the 14,000 photographs that were taken. Done in black and white, with strong contrast, the images are artistic in themselves. They reveal a treeless, stark world populated by people who are both rugged and spiritual. The core of the exhibition, however, is the paintings. Done on fabric, the majority of these paintings are religious paintings designed to be an aid in meditation and ritual. Most relate to Buddhism but some relate to earlier religions. Deemed to be in too poor condition to be used in religious practice, Tucci acquired paintings by purchase and by gift. A number of the paintings were discovered in a cave by one of his photographers. The ones on exhibit have now been restored. The paintings are full of religious symbols and meaning. Indeed, even the 17th century Arhat paintings, which look at first glance like a series of portraits, have symbolic meaning. The Arhats were disciples of the Shakyamuni Buddha. In each of the paintings, there is a dominant central figure. Around him are various figures and animals, each of which relates to some aspect of the central figure's life. Furthermore, the paintings relate to each other as they were to be hung in a certain order in the temple. Leaving aside their religious meaning, the paintings work as art. The figures are done delicately with relatively few lines, avoiding unnecesary detail. Beyond the figures are serene landscapes Flat and two dimensional, the images also have an abstract appeal. The restored colors are bright and appealing. “American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an intimate exhibition of works from 18 American artists illustrating the influence of Italy on their art. Drawn from the museum's collection, it includes drawings and sketches as well as a number of watercolor paintings.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, people interested in pursuing a career in art were encouraged to travel to Italy to study that country's long artistic history and culture. Of course, only a few had the means to make the arduous trip across the Atlantic from America. Still, beginning with Benjamin West in 1760, a number of American artists who would later achieve lasting fame made the journey. For example, Thomas Cole traveled to Italy in 1825 during a sojourn that took him to England and several European capitals. In Italy, he enrolled in art classes in Florence and made copies of works by Italian Renaissance masters. He also ventured out and made sketches of the Italian landscape. When he returned to the United States, he incorporated what he had learned in his landscapes. Thus, Cole's time in Italy can be said to have influenced the Hudson River School and American landscape painting. The exhibition contains a number of works done as part of such educational journeys. For example, there is a page of drawings by Thomas Sully of works by Michelangelo. There is also a watercolor copy by Julian Alden Weir of a painting by Botticelli. Italy's influence on American artists is shown in other ways. For example, J. Carroll Beckwith's chalk drawing called “The Veronese Print.” is a portrait of a Victorian era woman.. The reference to the Italian Renaissance master Paolo Veronese in the picture's title is to a print on the wall behind the sitter. Of course, American artists traveled to Italy for purposes other than studying. In 1879, James McNeil Whistler traveled to Venice to do a series of etchings for the Fine Art Society in London. While he was there, he did nearly 100 pastel drawings of the city. His “Note in Pink and Brown” is an intriguing drawing of a scene from one of Venice's canals. Whistler omits unnecessary detail to produce a vague, dream-like atmosphere. The highlight of the exhibition is a series of watercolors by John Singer Sargent. Born in Florence, Italy to expatriate American parents, Sargent traveled often to Italy. Most of these watercolors are landscapes of Venice or studies of architectural features. His watercolors are freer than the commissioned portraits for which he is best known. Furthermore, the colors are more vivid in the watercolors, more like those of his friend Claude Monet. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed