Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, a temporary exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, brings together the works of more than 50 artists to illustrate the contribution of women artists to modern art. The works come from the Museum's collection. Following World War II, the art establishment became dominated by abstract art. Although the artistic community at the time regarded itself as avant garde and progressive, it was not very tolerant of competing ideas. For example, the doors of the galleries were closed to artists working in more traditional or realist styles. So too, the galleries - - and too often the minds of the art world - - were largely closed to women artists even those doing abstract work. In the post war period, there were few, if any, mutual support groups for women artists. Watching my mother's struggle (see Art of Valda), what help she received seemed mostly to come from male artists who she had met while at the Art Students League of New York. Thus, for a woman artists to become recognized during this period was very much an act of individual achievement. This exhibit brings together the works of a number of woman artists who managed to overcome the prejudice of the time. It documents that women indeed contributed to the various schools of abstraction that dominated this period. Although the exhibit presents these works as works of women artists, it is important to note that these artists did not identify themselves as women artists and were not just competing against other women. The goal was to be artists who produced art that would compete in the marketplace of ideas with all other art regardless of the sex of the person who produced it. Perhaps the best known school of abstraction at the time was Abstract Expressionism. The enormous drip paintings of Jackson Pollock are hallmarks of this school. It was widely believed that such monumental works required masculine strength and gestures. However, the exhibit documents that women artists were producing similar works on a large scale. These artists included Lee Krasner, the wife of Jackson Pollock, who is represented in this exhibit by her work “Graea.” The curves of paint in this work have an almost floral, organic look. Abstract expressionism is about emotions and the work I found that evoked more reaction in me was Joan Mitchell's “Ladybug.” I found the color combinations visually pleasing and the lines moving and exciting. I also was impressed by Helen Frankenholer's “Trojan Gates.” Although a large canvas, it seemed more cohesive and unique in its approach than many abstract expressionist pieces. At the opposite end of the spectrum is “Reductive Abstraction.” Here, the idea was to remove the human touch from the work. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was much talk about human isolation and the potential that the mindless application of science would create a sterile environment in the future. Accordingly, some artists created futuristic works based upon mathematical or scientific concepts that were devoid of the human touch. Jo Baer's “Primary Light Group: Red, Green and Blue” is made up of three canvases, each of which is primarily a blank white square. Around the outer edge of each of the squares is a narrow black border. The three canvases differ only in that on one there is the color of the narrow space between the white area and the border. On one it is red; one, it in green; and one it is blue. The concept relies on the work of physicist Ernst Mach on the optical effects of placing colors next to black. I found the work too devoid of emotion. In addition, it reminded me of the demonstrations in high school science class when the teacher would illustrate some principle by using a clever but meaningless gimmick. The exhibit also shows that women artists made contributions in bringing abstraction to textiles. Vera Neuman's “Stone on Stone” made in the 1950s appears to be a forerunner of the designs used in the fashion revolution of the 1960s. A more disquieting work is Magdalena Abakanowicz's “Yellow Abakan,” a large, rumpled piece of fiber that hangs on the wall like the corpses in a butcher's freezer. It is not pretty but it evokes emotion. Finally, the exhibit concludes with Eccentric Abstraction.” These are works where the artist used materials not traditionally used in making art. The challenge in such works is to add enough creativity to the project so that it becomes a work of art rather than a pile of junk. Lee Bonteciu's “Untitled” employs pieces of used canvas conveyor belts to form a swirling, three dimensional object. Its industrial coloring gives it a dark, foreboding feel. Once again, it is not pleasant looking but it is evocative of emotion. This week, I wanted to talk about Claude Moent's “Bathers at La Grenouillere.” which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London.

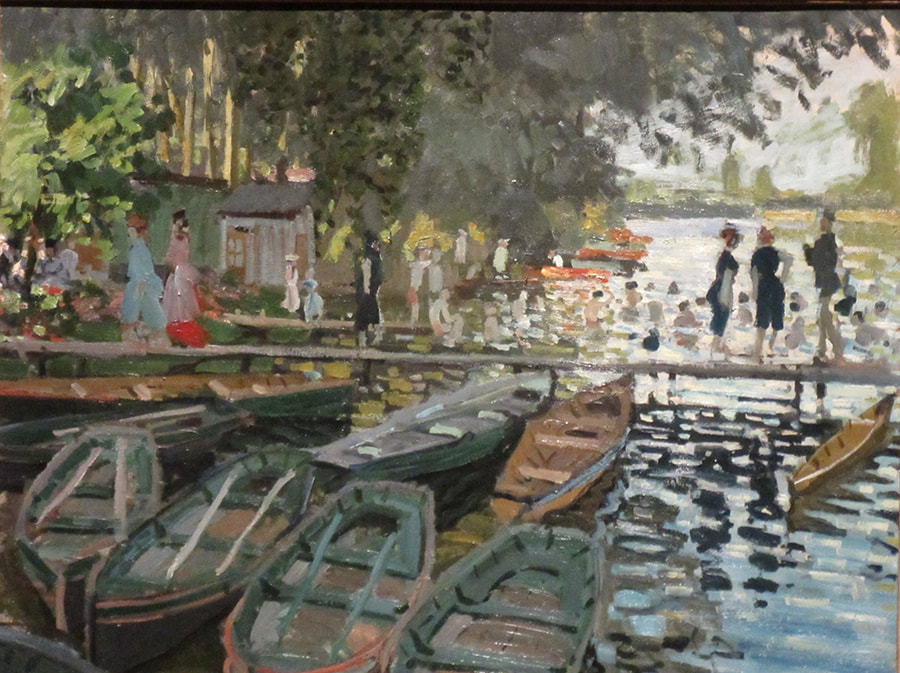

Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840. His father was a small businessman and the family moved to Le Harve about five years later so that his father could join a wholesale grocery firm that was owned by family members. Thus, Monet came from a middle class background. From an early age, Claude displayed a talent for drawing. Over time, he developed a reputation in Le Harve for his comic drawings and caricatures and was able to derive income from the sale of such works. With such a beginning, one might well expect that Monet would have developed into a portrait painter. However, one day when he went out to watch Eugene Boudin work on a landscape, he realized that landscapes were what he wanted to paint. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.” Friends and family recognized that Monet had talent. However, they were unanimous in saying that he needed to refine that talent by studying in the studio of an established artist. At that time, the most respected artists produced highly polished works with extensive modeling and glazing. The apex of the art world was history painting in which figures were depicted in scenes that told a story. Every artist's ambition was to have a work shown at the prestigious Salon in Paris. Monet was quite independent and bridled against such suggestions. Nonetheless, he went to Paris to study first at the Academie Suisse and later at the studio of Charles Gleyre, an established conventional artist. He did not like the conventional approach to the study of art. Although he often completed works in the studio, Monet preferred to work outdoors, painting directly from nature. However, his time in Gleyre's studio was not wasted because there he met Frederic Bazille and Pierre Auguste Renoir, who would be his compatriots in the Impressionist movement. Despite his dislike of conventional painting, Monet prepared and submitted several works to the Salon during this period. Most were genre paintings depicting contemporary people outdoors. In some respects, these works were reminiscent of Edourard Manet's work, Manet being something of a hero to Monet and his friends. They were more polished and the colors more subdued than Monet's later works. Nonetheless, the Salon rejected Monet's submissions. In the eyes of the juries, the works were unfinished and they failed to tell a story. During these years, Monet was able to sell some paintings but he often spent more than he earned.. Subsidies, first from his aunt and later by Bazille enabled him to continue on as an artist. In 1869, Monet moved with his mistress and young son to a cottage in Saint-Michel near Paris. Renoir was living with his parents nearby and so the two painters would often go out and paint the same subjects together. One of the places they were was La Grenouillere (the Frog Pond) a floating restaurant on the Seine at Bougival. The cafe was attached to a small island and to the riverbank by pontoons. There was a place to moor boats and a place for swimming. It was a very popular venue for socializing and summer fun. Indeed, it achieved such a reputation that Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugene came to have a look. Bathers at La Grenouiller is one of a series of studies Monet made in preparation for a larger more polished work that Monet submitted to the Salon. The larger work was rejected and later lost during World War II. What makes Bathers particularly interesting is that it is a forerunner of the style Monet would use in his later works when he was no longer working with the idea of submitting paintings to the Salon. The artist used color rather than lines to create the image. Figures, water, foliage are all described with a few bold brush strokes. The composition has a snapshot quality - - a scene of everyday life. Monet does not comment on the scene. He does not condemn it as people having frivolous fun nor does he praise it as welcome relief for the everyday worker. He just presents the scene and the viewer can make up his or her own mind. The picture can be dived into four quadrants with the pier dividing the picture horizontally and a vertical line right of center descending from the trees past the boats. Each section is a separate picture. However, the S curve of the river brings the composition together. A painting such as the Bathers would not have been possible only a few years before. The invention of the paint tube in the 1840s enabled Monet to easily transport his palette to the scene. Similarly, the invention of the metal ferrule made flat brushes possible. Such brushes enable Monet to work quickly and their use is documented by the flat brush strokes in this painting. The lesson here being that artists should not be afraid of employing new technology. This week, I am taking a look at Edouard Manet's A Bar at The Folies Bergere, which is in the collection of London's Courtauld Institute. It is considered Manet's last major work and remains one of his most famous. I wanted to discuss this painting this week because, as discussed below, this painting is in several ways similar to Manet's Corner of a Cafe Concert, which I discussed last week. (See article).

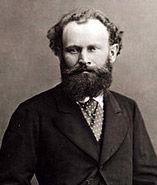

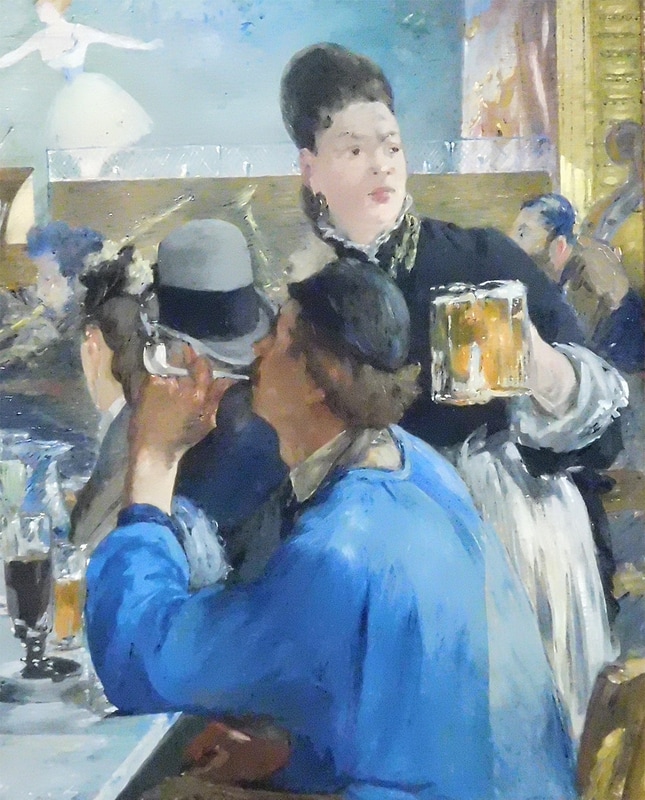

The painting presents a scene from a lively evening at the Folies Bergere. Manet frequented the cafes and music halls that were becoming popular in Paris in the second half of the 19th century often bringing with him a sketch pad. The Folies Bergere opened in 1869 and soon became one of the most popular of these venues. It offered operettas and pantomimes at that time. At the time of Manet's painting, the lavish, semi- nude spectaculars which are associated with the Folies Bergere were still in the future. The painting was done in 1882. Manet did a series of preparatory sketches and then re-created a bar in his studio. The central figure is a woman named Suzon who actually worked at the Folies Bergere. X-rays reveal that at one point, Manet painted the central figure with her arms crossed, thus showing that his thinking on the composition evolved during the course of its creation. A Bar at the Folies Bergere was exhibited at the Salon. As had occurred several times in the past, the work was controversial both as to the subject and the technique. At that time, many of the bar maids at the Folies Bergere were known prostitutes. As with Manet's earlier Olympia, the public was uncomfortable with having a prostitute be the center of attention. Also, as seen in the reflection in the mirror, she is in conversation with a customer - - not the kind of thing that is acknowledged in polite society even today. The criticism regarding Manet's technique mostly center upon whether he successfully portrayed the reflection in the mirror behind the central figure. Critics ever since have argued that such a reflection is optically impossible. Supporters have gone so far as to re-create and photograph the scene to show that the reflections do behave as Manet said. To me, both criticism miss the point. Like Corner of a Cafe Concert, A Bar at the Folies Bergere is essentially a portrait - - a view into the person portrayed. The central figure is the only figure modeled in detail. All of the rest of the painting is painted much more vaguely. The man in the reflection is almost cartoon-like. Manet draws us into her. Like the barmaid in Corner of a Cafe Concert, she is part of the scene but not part of the scene. She is lost in thought. Perhaps she is reacting to being propositioned. But perhaps she is only reacting to the tedium of yet another order for a bottle of beer. Whether she is a prostitute is irrelevant. The isolation and loneliness, whatever the cause, depicted in her face are what is important. Whether the reflection is optically correct is also irrelevant. While the scene has the feel of a snapshot, it is not a photograph. The reflection is merely a vehicle for conveying the good times atmosphere of the music hall. It is there to provide a contrast to the emotions depicted in the central figure's face. As in Corner of a Cafe Concert, Manet has once again created a pattern of flat rectangles to form the background for the portrait. Here, the rectangles are more broken by hints of figures and chandeliers but the concept is the same. Once again, it is a forerunner of the geometric art of the 20th century. Another similarity to Corner of a Cafe Concert is the way the glassware is painted. As discussed last time, the large beer mug in the center of Cafe, is very simply painted. Here, the glass and the bottles on the bar are also very simple. The glass and the bowl are just a few lines of white and gray paint over the background colors. A Bar at the Folies Bergere represents a development of the concepts that Manet used four years earlier for Corner of a Cafe Concert. Both are cafe scenes but at the center of each are individuals who are separated from their surroundings. Also, as discussed above, they employ similar artistic techniques to convey the message.  This week, I thought I would talk about Edouard Manet's Corner of a Cafe Concert, a painting which I saw in the National Gallery in London. I like Manet's work not just because it is pleasing to the eye but because it conveys emotion. I particularly like his ability to make faces thought provoking. Edouard Manet was a French artist born in 1832 in Paris. His father was a successful jurist while his mother was the daughter of a diplomat. His parents wanted him to enter one of the respectable professions rather than pursue his love of art. It was not until after Manet had failed his entrance exams for the naval academy that his family relented and allowed him to study art. While his family's resistance to his desired career must have been emotionally difficult for the young Manet, his family background provided a firm foundation for his art. Because he was financially secure, he was able to travel around Europe to view the works of past masters and to avoid starvation in the process of establishing himself as a successful artist. Manet was a man of contrasts and contradictions. He is widely acknowledged as setting art on a new course and has been called the first modern artist. Yet, he was influenced by and drew from traditional artists such as Velazquez and Goya. He scandalized the art establishment of the day by submitting works such as Dejuner sur iHerbe and Olympia to the Salon but accepted the honors of the establishment such as a medal from the Salon as well as the Legion of Honor. He was a friend of the Impressionists and influenced their work but rejected their invitations to exhibit with them preferring instead to try to have his works accepted by the Salon. An opponent of Napoleon III and a republican intellectual, Manet nonetheless joined the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War rather than flee the country as some of the artists in his circle did. Along the same lines, Manet's artistic style encompasses diverse elements. He favored broad, strong brush strokes and alla prima painting where the forms are rendered by the application of raw color rather than modeled in multiple glazed layers as was done in the popular art of the time. At the same time, his use of black paint recalls the aforementioned Spanish masters. Manet was a painter of modern life but at the same time, there are echoes of Renaissance masterpieces in his works. Corner of a Cafe Concert presents a scene of modern life. Manet enjoyed going to the Parisian cafes that were becoming popular in the 19th century and often sketched scenes that he saw there. This painting, created around 1878, is of a scene at the Brasserie de Reichshoffen. The image is not unlike a snap shot or a photo taken with an iPhone. We see people drinking and enjoying themselves while a dancer performs on stage. You can almost here the clinking of glasses, laughter and the music. In the end, however, the painting is a portrait. The central figure is a waitress who is in the process of serving mugs of beer. Hers is the only face that can be seen clearly in the picture. Something has distracted her and she is looking off beyond the bounds of the canvas. Perhaps someone is signaling her for a drink, perhaps people are arguing, or perhaps someone she knows has walked into the cafe. Whatever it is, she is lost in thought. The drinkers, conversation, the show are as irrelevant to her as she is to them. Thus, she is both at the center of the scene but at the same time not really part of the scene. The face of the waitress is quite simply done. There is very little detail or modeling. The eyes and nostrils are the most dominate and appear to be touches of burnt umber. The same color, perhaps thinned mixed with white was used in several of the other features. In her hand is a large beer mug. It too is simply done. A few strokes of white paint here and there make up the boundaries of the glass. Splashes of yellow ochre and burnt sienna depict the contents. Another thing that I noticed about this work is the use of rectangles. The upper portion of the picture - - the area framing the waitress' face - - is made up of a series of rectangles. They form the stage where the dancer who is off to the left is performing. However, these flat spaces also form an abstract design similar to those used as the subject of paintings by artists in the first half of the 20th century. Corner of a Cafe Concert was originally part of a larger work. At one point during its creation, Manet decided to cut the work in two. He then developed the two halves independently. I like knowing this because it lends a master's approval to the notion of physically altering a work. Sometimes when I am doing a picture, I reach a point where I realize that the picture as a whole does not really work. However, there are some nice bits that could work on a stand alone basis if only they had been created on their own canvas or piece of paper. What Manet has done here shows that it is perfectly permissible to cut down a work physically in order to create a picture that does work. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed