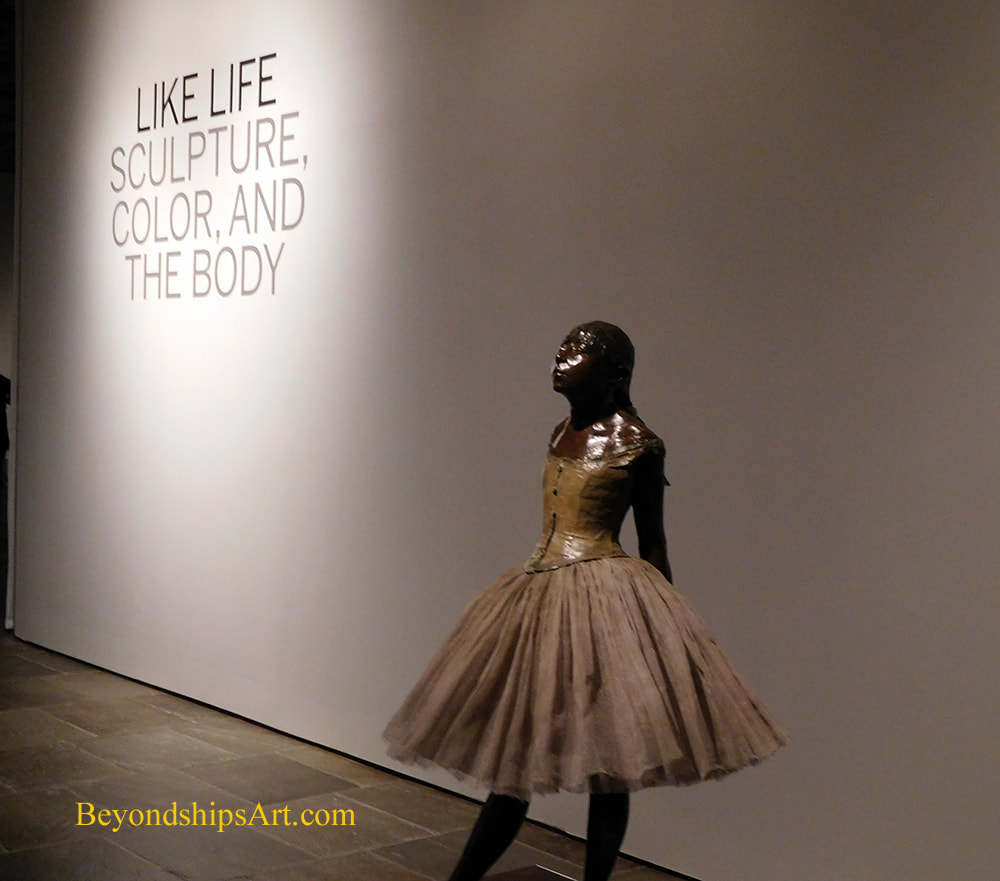

Ocean liners have earned a place in history. During the era of ocean liner travel, these ships transported millions of immigrants from Europe to North America and Australia, they provided a transportation link between the nations of the world, carried troops, acted as hospitals during times of war and were at the forefront of technology. Thus, one might well expect to find an exhibition about ocean liners at a history museum. But what do ocean liners have to do with art? “Ocean Liners: Speed and Style” at London's Victoria and Albert Museum explores this question with 250 objects, including paintings, sculpture, and ship models, alongside objects from shipyards, wall panels, furniture, fashion, textiles, photographs, posters and film. Beginning with Brunel’s steamship, the Great Eastern of 1859, the exhibition traces the design stories behind some of the world’s most luxurious liners including the Beaux-Arts interiors of Kronprinz Wilhelm, Titanic and its sister ship, Olympic; the floating Art Deco palaces of Queen Mary and Normandie; and the streamlined Modernism of SS United States and QE2. The answer to the above-stated question is that ocean liners intersected with art in quite a few ways. First, ocean liners intersected with art as architecture. Beginning in the early 20th century, ocean liners grew from being mere vehicles for transportation into environments in which thousands of people lived. Streamlined, they took on lines which influenced architecture both at sea and on land. Similarly, they also influenced the engineering design of the day. Just as a great building is art, so is a great ship. Second, there is interior design. In order to attract passengers, particularly, well-to-do passengers, the ocean liners developed luxurious interiors. At first, the shipping lines sought to imitate the grand hotels ashore but over time they created their own styles. Furthermore, as ocean liners became symbols of national pride, they were filled with artistic treasures. Art Deco works from the 1930s French liner Normandie can now be found in major museums such as the Metropolitan Museum. Similarly, the interiors of Cunard Line's Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth showcased works from around the British Empire. The examples of ocean liner furniture and paneling included in the exhibition demonstrate the quality of this decoration. Along the same lines, the shipping lines did not just rely on word-of-mouth to attract customers. In order to lure passengers aboard, they created posters and brochures advertising the ships. Whereas today's advertising relies primarily on glossy photographs, these advertisements often involved drawings and other artistic depictions of the ships and life at sea. In addition, the graphic layouts were often artistic. The ocean liners also influenced fashion. During the Golden Age of Ocean Liner travel, people dressed while at sea. Elegant gowns, dinner suits, blazers and day wear were necessities for a first class voyage. Passengers displayed the latest designs and designers were inspired to create new designs. Examples of fashions worn aboard ship are included in the exhibition such as a Christian Dior suit worn by Marlene Dietrich as she arrived in New York aboard the Queen Mary in 1950 and a striking Lucien Lelong couture gown worn for the maiden voyage of Normandie in 1935. At the same time, artists were inspired to create works featuring ocean liners. These included not just traditional maritime paintings of ships but also abstract works. Several Cubist-style works are included in the exhibition. Filmmakers were also inspired by the ocean liner image. The exhibition presents clips from a number of major motion pictures that were either about or set on ocean liners. Overall, the exhibition provides a good introduction to ocean liners and their artistic significance. Along the way, it introduces the major ships and it tells their story. The lighting and use of technology also enhance the exhibition.  “Birds of a Feather: Joseph Cornell's Homage to Juan Gris” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small exhibition that brings together a dozen of Cornell's shadow boxes along with the painting by Juan Gris that inspired Cornell. Joseph Cornell was born in 1903 outside of New York City. He was the eldest of four children. When his father died in 1916, the family was left in bad financial circumstances and had to move into the city. Joseph dedicated most of his life to supporting the family including a younger brother who had cerebal palsy. Painfully shy, Cornell never married and had few relationships and friendships. Cornell had little formal education. However, he was well-read and interested in cultural activities. Accordingly, he spent much of his free time exploring museums and art galleries. As a result, he began to develop his own art. The primary medium used by Cornell was the shadow box. He would take various objects that he discovered on his trips around New York and assemble them together. These juxtapositions of found objects had a surrealistic flavor and he was embraced by the Surrealists and New York's artistic community. On one of his visits to an art gallery, he saw a painting by Juan Gris that he found striking. Gris was born in Spain in 1887 but moved to Paris in 1906 where he became part of the avant garde scene. Although not the inventor of Cubism, he brought that style forward and developed it. The work that inspired Cornell was “The Man at the Cafe.” In it, Gris depicted the criminal mastermind in a popular series of novels. This shady character is almost entirely obscured by the newspaper he is reading. The shadow from his fedora blocks out his face. Wood grained paneling mixes the background and the figure. Done in the Cubist style, it is divided into geometric planes. Cornell made 18 shadowboxes, two collages and a sand tray in the series inspired by Gris' painting. Like Gris' painting, he incorporated printed pages and trompe l'oeil wood grain in these works. There is also a central figure but instead of a criminal mastermind, the figure is a cockatoo. The shadow boxes are much smaller than Gris' painting. Consequently, they are much more intimate visually. Thus, while they may be rooted in the painting, they are a much different visual experience.  “Provocations: Anslem Kiefer at the Met Breuer” is a large exhibition drawn from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection of works by the contemporary German artist. Anslem Kiefer was born in Germany two months before the end of the Second World War in Europe. Kiefer planned from childhood to be an artist. However, when he entered the University of Freiberg, he began as a pre-law and language student. However, he soon switched to the study of art and went on to studying art at academies in Karlsruhe and Dusseldorf. He studied informally with the artist Joseph Beuys. Now a well-established artist, he lives in the South of France. Keifer's work has been primarily concerned with relating German history and culture to the present day. In particular, he has sought to confront the Nazi era. Following the end of the Second World War, the symbols of the Nazi era were outlawed in Germany. The victorious Allies were concerned that the Nazi movement could be revived if these symbols were allowed to be displayed. For many of the vanquished German people the ban made it easier to forget the horrors that had been committed in their name. However, by the 1960s, German intellectuals were arguing that the Germany had to come to terms with its past. In 1969, Kiefer came to public attention with a series of photographs that he had taken of himself in his father's Wermacht uniform giving the Nazi salute. The photos were taken with a background of historic monuments around Europe and by the seaside. Audiences wondered whether the photos were meant to be ironic or as praise for the Nazis. Kiefer's objective was to cause people to confront rather than bury the past. Kiefer has over the years expanded the scope of his work to include a broad range of German history and culture. However, since the Nazi propaganda machine conscripted much of German music, myth, legend and history, the specter of the Nazi era is never far away. Described as a Neo-expressionist, Kiefer has used a variety of mediums in his work. In addition to traditional painting and photography, his works have incorporated such things as earth, lead, straw and broken glass. He is also known for works on a monumental scale. One such monumental work displayed in the exhibition is “Bohemia Lies by the Sea” (1996). The painting has some of the force of an abstract expressionist work. However, it is actually a scene of a rutted country road extending through a field of poppies. The title is taken from an Austrian poem in which the poet longs for utopia but recognizes that it is unreachable just as landlocked Bohemia can never be by the sea. The connection to the Nazi era is that Bohemia is in the Sudetenland annexed by the Nazis just before the war. Furthermore, poppies are a symbol for lives lost in war. While Kiefer is known for his large works, I found myself drawn more to some of the smaller works in the exhibition. For example, in “Herzeleide” (Suffering heart), Keifer based his watercolor on the image in a Nazi era book of a mother looking at a document informing her that her son has been killed. Nazi propaganda exalted such sacrifices. In his painting, Kiefer has replaced the document with an artist's palette. “My Father Pledged Me A Sword” is based upon Wagner's Ring Cycle operas. In the operas, Woton, king of the gods, thrust a sword into in an ash tree. Later, his son Sigmund is in need of the sword and cries out for it. However, Kiefer has painted the sword not in a tree but in a rock atop a high cliff overlooking a fjord - - much more difficult to retrieve. Even assuming aguendo that the viewer knew nothing about German history or culture, Kiefer's art still works. The works are well composed. Sometimes bleak and sometimes harsh, they are always emotionally powerful and thought-provoking. “Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now)” at the Met Breuer in New York City surveys 700 years of Western sculpture focusing on works that in one way or another attempt to approximate life. The works occupy two floors of the museum and are drawn from the Met's own collection as well as works on loan from elsewhere.

Western sculpture has long depicted the human form. However, at least since Medieval times, the majority of the sculptures of the human body have not tried to convey a life-like appearance. To illustrate, marble statues in museums are usually left white and bronze statues in the park are usually the color of the metal. They are meant as depictions of the human form rather than attempts to re-create a real person. No one would mistake these statues for real people. Throughout this period, however, there have been attempts to cross the border line traditionally observed by sculptors. Most often this has been done by painting the sculpture to give it the color of a real person. However, it has also been done by incorporating elements such as human hair in the sculpture or by dressing the sculpture in clothing. Plastics and similar materials have made it easier to approach a life-like look. This exhibition looks at the various ways sculptors have striven to create a life-like image. There are examples of religious sculptures painted to make the saint or other subject appear alive. A life-like appearance was thought by some to be helpful in persuading viewers to believe. Others, however, condemned such depictions as being akin to idolatry as people might worship the statue rather than the concept behind the statue. Edgar Degas clothed his famous sculpture of a young ballet dancer with an actual ballet costume. While the image is now very familiar, it was unsettling to 19th century viewers when it was first shown in Paris. Sculptures did not wear actual clothing. More recently, artists have not only clothed figures but by using technology and artificial materials have created figures so life-like that the viewer is left wondering whether the figure is really just someone standing still. Beyond the novelty of such statues, they can be used to capture a moment in time when surrounded by furniture or other props.. Traditionally, statues remained in one pose. Mannequins and other figures with movable parts generally were not considered art. However, the exhibition shows that artists have in the past and now have used movable parts in their sculpture. The exhibition does not present the works chronologically but rather by theme. For example, one gallery is devoted to the Pygmalion myth, in which the gods grant a sculptor's wish that the statue that he has created turn into a real woman. The works include a 19th century painting, a series of drawings by Pablo Picasso and John De Andrea's 1980 sculptural scene in which figures made of polyvinyl polychromed in oil depict the artist and his sculpture with life-like detail. “Life-like” is a phrase often used at funerals to describe the mortician's treatment of the corpse. Regardless of how closely a sculpture approximates life, the fact remains that it is not alive. Thus, there is a morbid element to this line of sculpture. In fact, one of the works is a corpse. The 19th century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham specified in his will that after his death his body would be dissected. After that was done, the body was to be preserved and brought out at meetings at the University of London His wishes were followed. Over the years, the head deteriorated and so a wax head was mounted on the body. The clothed body with its wax head is seated in a glass case. The smile indicates that Bentham would have enjoyed the viewers' discomfort. Along the same lines, there are sculptures with blood and/or vital organs showing. The fact that the sculptures are life-like makes these mutilations rather grisly even though no real person was involved. Although sometimes unsettling, overall, this is an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition. The exhibition shows that an inanimate object can be made to appear strikingly like a real person. Yet, oddly enough, in art, the essence of a person often comes through better in a less realistic image. Thus, one is left to ponder what it is that sets a living being apart.  "Unknown Tibet: The Tucci Expeditions and Buddist Painting” at the Asia Society Museum in New York City presents a selection of Tibetan paintings collected during the expeditions of Giuseppe Tucci during his expeditions to Tibet along with some of the photographs that were taken during the expedition. The paintings in the exhibit are from the Museum of Civilisation-Museum of Oriental Art "Giuseppe Tucci," in Rome and are being shown for the first time in the United States. Giuseppe Tucci was a writer, scholar and explorer who made eight expeditions to Tibet during the period 1926 to 1948. Up to that time, Tibet was a remote mystery and Tibetan culture largely unknown outside of Tibet. Tucci traveled some 5,000 miles on foot and on horseback across the Tibetan plateau, In addition to meeting people and seeing places, he obtained permission to collect examples of Tibetan culture for study outside the country. In addition, Tucci brought along photographers to document the expeditions. Their mission included photographing monuments, cultural artifacts, people and their occupations. In other words, they made a systematic effort to document this ancient culture before it vanished. The exhibition presents copies of some of the 14,000 photographs that were taken. Done in black and white, with strong contrast, the images are artistic in themselves. They reveal a treeless, stark world populated by people who are both rugged and spiritual. The core of the exhibition, however, is the paintings. Done on fabric, the majority of these paintings are religious paintings designed to be an aid in meditation and ritual. Most relate to Buddhism but some relate to earlier religions. Deemed to be in too poor condition to be used in religious practice, Tucci acquired paintings by purchase and by gift. A number of the paintings were discovered in a cave by one of his photographers. The ones on exhibit have now been restored. The paintings are full of religious symbols and meaning. Indeed, even the 17th century Arhat paintings, which look at first glance like a series of portraits, have symbolic meaning. The Arhats were disciples of the Shakyamuni Buddha. In each of the paintings, there is a dominant central figure. Around him are various figures and animals, each of which relates to some aspect of the central figure's life. Furthermore, the paintings relate to each other as they were to be hung in a certain order in the temple. Leaving aside their religious meaning, the paintings work as art. The figures are done delicately with relatively few lines, avoiding unnecesary detail. Beyond the figures are serene landscapes Flat and two dimensional, the images also have an abstract appeal. The restored colors are bright and appealing. “American Painters in Italy: From Copley to Sargent” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is an intimate exhibition of works from 18 American artists illustrating the influence of Italy on their art. Drawn from the museum's collection, it includes drawings and sketches as well as a number of watercolor paintings.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, people interested in pursuing a career in art were encouraged to travel to Italy to study that country's long artistic history and culture. Of course, only a few had the means to make the arduous trip across the Atlantic from America. Still, beginning with Benjamin West in 1760, a number of American artists who would later achieve lasting fame made the journey. For example, Thomas Cole traveled to Italy in 1825 during a sojourn that took him to England and several European capitals. In Italy, he enrolled in art classes in Florence and made copies of works by Italian Renaissance masters. He also ventured out and made sketches of the Italian landscape. When he returned to the United States, he incorporated what he had learned in his landscapes. Thus, Cole's time in Italy can be said to have influenced the Hudson River School and American landscape painting. The exhibition contains a number of works done as part of such educational journeys. For example, there is a page of drawings by Thomas Sully of works by Michelangelo. There is also a watercolor copy by Julian Alden Weir of a painting by Botticelli. Italy's influence on American artists is shown in other ways. For example, J. Carroll Beckwith's chalk drawing called “The Veronese Print.” is a portrait of a Victorian era woman.. The reference to the Italian Renaissance master Paolo Veronese in the picture's title is to a print on the wall behind the sitter. Of course, American artists traveled to Italy for purposes other than studying. In 1879, James McNeil Whistler traveled to Venice to do a series of etchings for the Fine Art Society in London. While he was there, he did nearly 100 pastel drawings of the city. His “Note in Pink and Brown” is an intriguing drawing of a scene from one of Venice's canals. Whistler omits unnecessary detail to produce a vague, dream-like atmosphere. The highlight of the exhibition is a series of watercolors by John Singer Sargent. Born in Florence, Italy to expatriate American parents, Sargent traveled often to Italy. Most of these watercolors are landscapes of Venice or studies of architectural features. His watercolors are freer than the commissioned portraits for which he is best known. Furthermore, the colors are more vivid in the watercolors, more like those of his friend Claude Monet.  “Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a large exhibition that places in context much of the art created in France from the French Revolution to World War I. It explains why so much attention was paid by artists such as the Impressionists to the out doors as a subject. Extending from the late 18th century through the 19th century a passion developed in France for parks and gardens. Several factors came together to fuel this passion. First, as a result of the French Revolution, the parks and hunting reserves that had heretofore been open only to royalty and the aristocracy, became open to everyone. This access helped to open the eyes of the public to the beauties of nature. Second, the Industrial Revolution also changed the character of society. The middle class grew and people had more leisure time. They wanted green spaces, both public parks and private gardens, where they could escape from the stresses and pollution that were the less attractive side effects of industrialization. Accordingly, in the grand re-design of Paris that took place in the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann included tree-lined boulevards and some 30 parks and squares. Other cities and towns throughout France followed suit. Third, it was also a period of exploration and travel. Exotic plants were being brought back to France, stirring the public imagination. The Empress Josephine, first wife of Napoleon, and a celebrity in her day, spurred public interest in such plants by making her greenhouse at Malmaison a horticulture hub for exotic species. Artists were not immune from these forces. The natural world, depicted in landscapes and in still lifes, had long been a subject for art. However, a new enthusiaum developed. The painters of the Barbizon School took inspiration from the former royal hunting grounds at Fontainebleau. Later, the Impressionists, whose aims included depicting scenes of modern life, reflected public's passion for parks, gardens and the natural world in their works. While this exhibition includes earlier works, the Impressionists and the artists that they influenced dominate the exhibition. For example, in the gallery “Parks for the Public,” we see works by Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and others of former royal hunting reserves. However, you also have masterpieces by Calude Monet and Camille Pissaro of city parks in Paris. There is also a wonderful watercolor by Berthe Morrisot “A Woman Seated at a Bench on the Avenue du Bois” as well as a study by Pointillist George Seurat for “"A Sunday on La Grande Jatte." In the gallery “Private Gardens,” the works reflect the fact that people wanted to have their own green spaces where they could cultivate plants and escape from the outside world. Many artists were also amateur gardeners during this period. Of course, the dominant figure here is Claude Monet who was painting garden scenes long before he created his famous garden at Giverney. However, lesser known watercolors of garden scenes by Renoir and by Cezanne should not be overlooked. With regard to portraiture, we see that the artists blurred the distinction between portraits and genre painting. They are both depictions of individuals and scenes of everyday life. As a result, the identity of the sitter is no longer paramount if important at all to the success of the work. Furthermore, nature is an equal partner in these scenes, not just a background. To illustrate, Edouard Manet's “The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil” is a portrait of Monet and his family. The figures are arranged in a relaxed manner rather than in traditional portrait poses. Thus, it is also a scene of everyday life. Moreover, it would be just as successful if the figures were an unidentified family because it is a captivating garden scene. The passion for nature also brought about a revival of interest in floral still life painting. The exhibition presents examples by Manet, Monet, Cassat, Degas, and Matisse to name a few. But Vincent Van Goghs paintings of sunflowers and irises attract the most viewers. Given the popularity of the Impressionists and their broader circle, one would expect any exhibit in which they are prominent to be successful. However, the Met has done a good job here of supporting the theme of the exhibition. In addition to the paintings, there are drawings, prints contemporary photographs and objects relating to this theme. The signage is also good. “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” at the Museum of Modern Art presents the work of the artist who led the development of the modernist movement in Brazil. During the 1920s, Tarsila, as she is widely known in Brazil, developed a distinctive style that was truly Brazilian. MOMA has assembled over 100 works drawn from various collections including some of her landmark paintings to document this development.

Tarsila was born in Capivari, a small town near Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1886. Her family owned coffee plantations. Although it was unusual at that time for girls from affluent families to pursue higher education, Tarsilia was allowed to pursue her interest in art, both in Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain. Her instructors were conservative, academic artists. In 1920, after the end of her first marriage, Tarsila went to Paris in 1920 to study at the prestigious Academie Julian. Her studies were again in the academic tradition. Meanwhile, a modern art movement had taken root in Brazil. The landmark Semana de Arte Moderna was a festival that called for an end to academic art. Upon Tarsila's return to Brazil, she discovered modern art became a leader in this movement, one of the five artists and writers in the Grupo dos Cincos. In 1922, she returned to Paris and studied with several Cubist artists including Ferdinand Leger and Andre Lehote. However, she continued to think in terms of Brazil. She painted “A Negra,” an abstract portrait of an Afro-Brazilian woman. Returning to Brazil, she embarked upon a tour around the country. The drawings of the countryside and everyday life she made while on this journey served as inspiration for later paintings. Her traveling companion was the writer Oswald de Andrade wrote a manifesto “Pau-Brasil” calling for truly Brazilian culture. She married Andrade in 1926. Tarsila made another journey to Paris in 1928 where she came into contact with surrealist art. (It should be noted that Tarsila did not live like a starving artist in Paris. A renown beauty from a wealthy family, she lived a lavish lifestyle, mixing with famous personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals). That same year, she painted “Abaporu” (the man who eats human flesh) as a birthday present for her husband. He used the image for the cover of his “Manifesto of Anthropology,” which called upon artists to cannibalize European culture and other influences in order to create a distinctive Brazilian culture. The painting and the manifesto are considered landmarks in the development of Brazilian culture. Tarsila's family fortune was all but lost as a result of The New York Stock Exchange crash of 1929 and the following Depression. Her marriage to Andrade ended the following year. In 1931, Tarsila traveled to Moscow with her new boyfriend, a communist doctor. There she was influenced by Socialist Realism. Her subsequent work was primarily concerned with social issues. The exhibition at MOMA focuses on the decade beginning with her journey to Paris in 1920. It demonstrates how Tarsila's work evolved incorporating over time elements of Cubism, Brazilian folk art and Surrealism while retaining her own style. Although she was influenced by each of these schools, she did not become part of them. Hers is a distinctive style: flat two dimensional; populated with simplified, distorted figures and landscapes; often with geometric backgrounds. It is also clearly Brazilian, not only in the choice of subject matter but in the selection of colors. In short, it is what Andrade was calling for - - a synthesis of a number of influences producing a truly Brazilian art. The exhibit also includes some works after her trip to Russia. “The Workers” (1933) was one of the first paintings in Brazil dealing with social issues. It reflects the influence of Soviet painting both in subject matter and palette. Incorporation of this soulless style was not a happy addition to Tarsila's arsenal. The work does not have the life of her earlier works and the treatment of the subject matter is much like what numerous other artists were doing at the time. However, it does serve to spotlight how special her work was during the preceding decade.  Royal Caribbean's Anthem of the Seas has a sophisticated contemporary décor. In fact, it is often said that the ship's decor looks more like a ship from Royal's premium affiliate Celebrity Cruises than the Las Vegas style décor of some of Royal's earlier ships. Accordingly, the art collection on Anthem is less aimed at eliciting a “wow” and more aimed at contributing to the ship's upmarket atmosphere. Anthem's art collection was assembled in partnership with International Corporate Art. It includes some 3,000 works of art. Almost all are contemporary works. The theme of the collection is “What Makes Life Worth Living.” According to the booklet about the collection, this theme encompasses “people, leisure, fashion, art &literature, food, adventure, entertainment & nature.” This scope is perhaps too broad as it is difficult to discern the theme just by walking around the ship and viewing the various works. However, knowing the theme is not vital to enjoying the art. Several large installations are included in the collection. At the center of ship's public areas is a grand chandelier created by Rafael Lorenzo Hemmer called “Pulse Signal.” It consists of some 200 light bulbs suspended from cords and arranged into a pleasing contemporary shape. The lights blink on and off in various arrangements thus changing the shape of the piece and the atmosphere of the area. It is a visually interesting piece. Guests can control the blinking of the lights by putting their hands on a pad that is located beneath the chandelier. The blinking is then synchronized with the guest's pulse. This does allow for viewer involvement with the art but I find it somewhat gimmicky and unnecessary. Just aft of the chandelier, ascending up the atrium is the prettiest piece in the collection, Ran Hwang's “Healing Garden.” Dark tree branches with bright blossoms are set against a gold background. The work recalls traditional East Asian cherry tree paintings. However, the artist has included non-traditional materials such as crystals, buttons and pins, which give the work a glamorous look. Going further aft, you come to a monumental sculpture by Richard Hudson. It is a swurling mass of highly polished metal. Although entitled “Eve”, it has become widely known as “The Tuba” because of its twisted horn-like shape. Despite this unfortunate nickname, it is an important piece consistent with the upscale shops, the cosmoploitan wine bar and the specialty restaurant that surround the plaza in which it is the centerpiece. You can find works that contribute to Anthem's sophisticated atmosphere throughout the public areas and on the staircases. However, there is also whimsy in the collection. For example, in each of the elevators there is a giant image of an animal. Deming Harriman has manipualted these images so that the various animals are wearing items of human clothing. By adding these items, the artist gives the animals human personalities, making the images both amusing and a commentary on human foilbles. Atop the ship is a larger than life sculpture of a giraffe wearing a swimming costume and an inner tube. Known as “Gigi” this lovable character by Jean Francois Fourtou marks the ship's amusement park area. There is also art along the corridors leading to the passenger cabins. These include contemporary photos staged so as to look like advertisements or scenes from 1950s America. There are also posters with inspirational slogans like the ones that the youth culture used to decorate college dormitories in the 1960s. Overall, the Anthem collection is successful. The theme is perhaps too broad to present a coherent message. However, the pieces are visually pleasing and often thought provoking, Also together, they serve to support the overall atmosphere of the ship. Above: Richard Hudson's Eve provides a centerpiece for one of the ship's plazas.

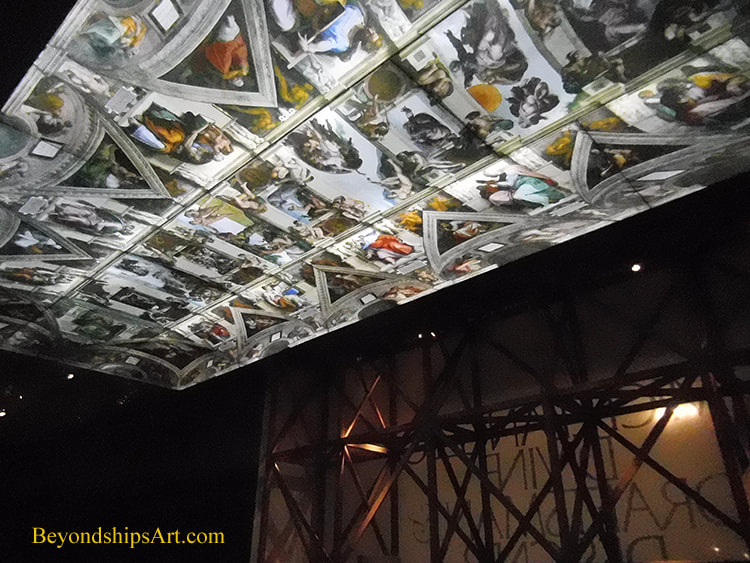

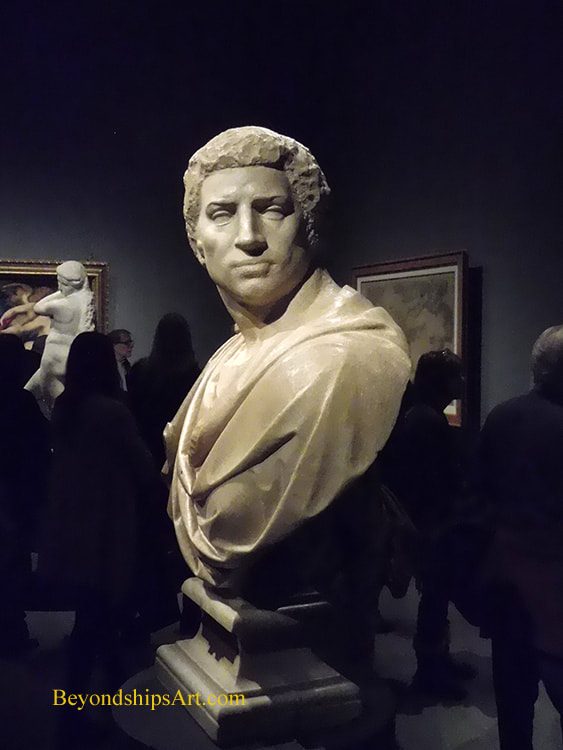

Below left: Ran Hwang's “Healing Garden” in the ship's atrium. Below right: "Pulse Signal" by Rafael Lorenzo Hemmer is in the center of Atrium's public area.  “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art presents some 200 works by Michelangelo and his contemporaries. It includes 133 of Michelangelo's drawing as well as three of his marble sculptures gathered from 48 museums and private collections. It is a monumental exhibit. Although Michelangelo considered himself to be primarily a sculptor in marble, he was also a painter and an architect. In this exhibition, we see that the foundation of his art in all of these disciplines was drawing. But more than mere draftsmanship, his drawing reflected a quality of design. The exhibition uses the Italian word disego to capture this concept. Very few of the works in this exhibition were meant for public display. Rather, they were preparatory drawings made in order to work out ideas that would be used in paintings or sculptures. Others served to illustrate ideas for buildings. Because they were made further back in the creative process, they reveal something of how Michelangelo developed his ideas. To illustrate how some of the drawings led to finished works, the exhibit has a one quarter size reproduction of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel displayed ion the ceiling of one of the galleries. Visitors can look up from Michelangelo's drawing and see how that idea was used in the final masterpiece. The exhibit also places the drawings in context. For example, the exhibit is open about Michelangelo's love of young men and explains that his “divine heads” were drawings that he did of those men and as presents for them. It also discusses his platonic relationship with the poet Vittoria Colonna and presents the drawings that he did when he came under her influence. It also looks at his relationship with other artists. To illustrate, Raphael began to achieve success in Rome at a time when Michelangelo was living in Florence. In order to compete with Raphael, Michelangelo fed ideas to the painter Sebastiano. Michelngelo's powerful marble bust of Brutus is presented along with a Roman statue that inspired Michelangelo and a bust of Julius Caesar made by a contemporary of Michelangelo. This allows us to see the debt that Michelangelo owed to the ancients as well as how his work broke with what was fashionable when Michelangelo created his Brutus. Michelangelo is one of the best known artists of all time. Yet, this exhibit sheds light on his creative process and career that may not have been generally appreciated before. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed