|

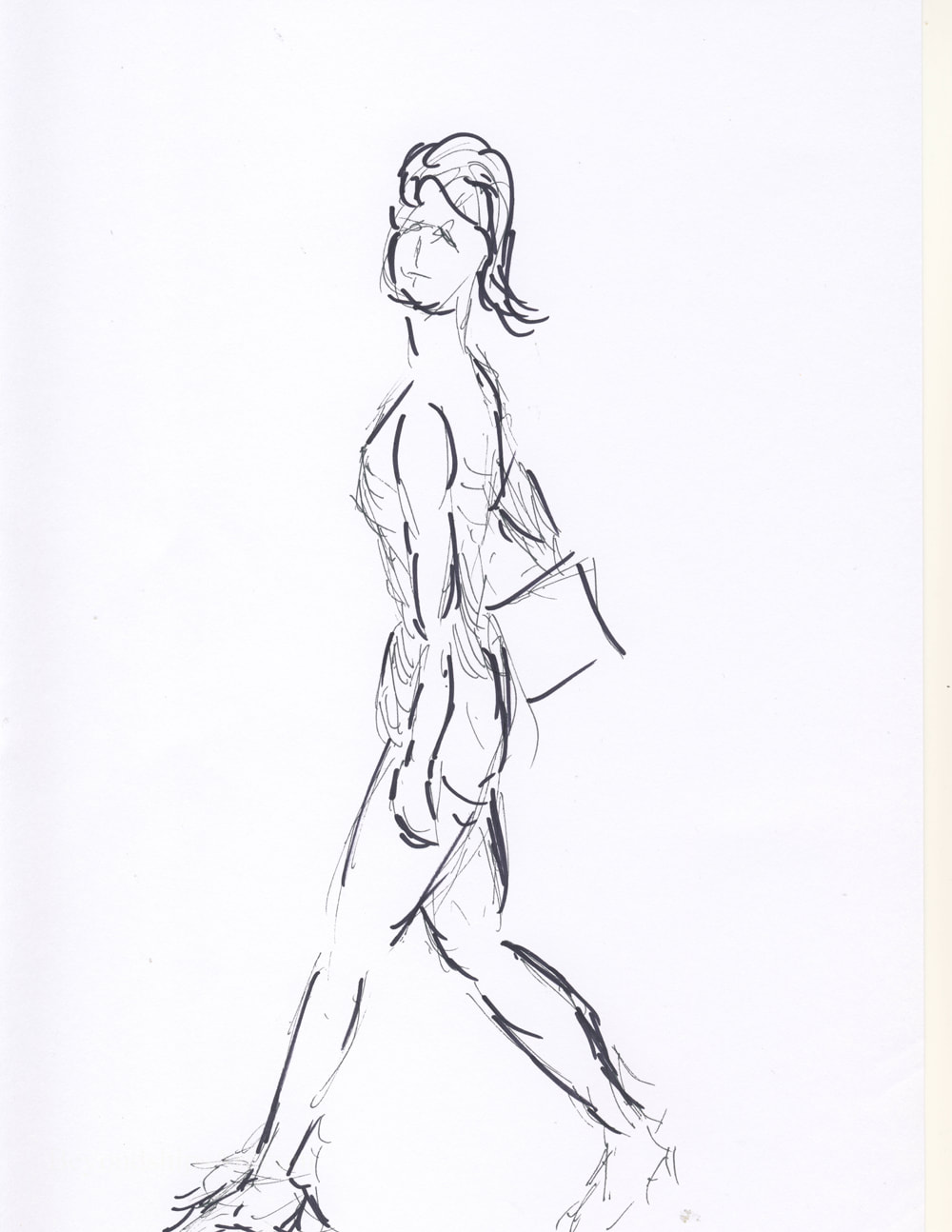

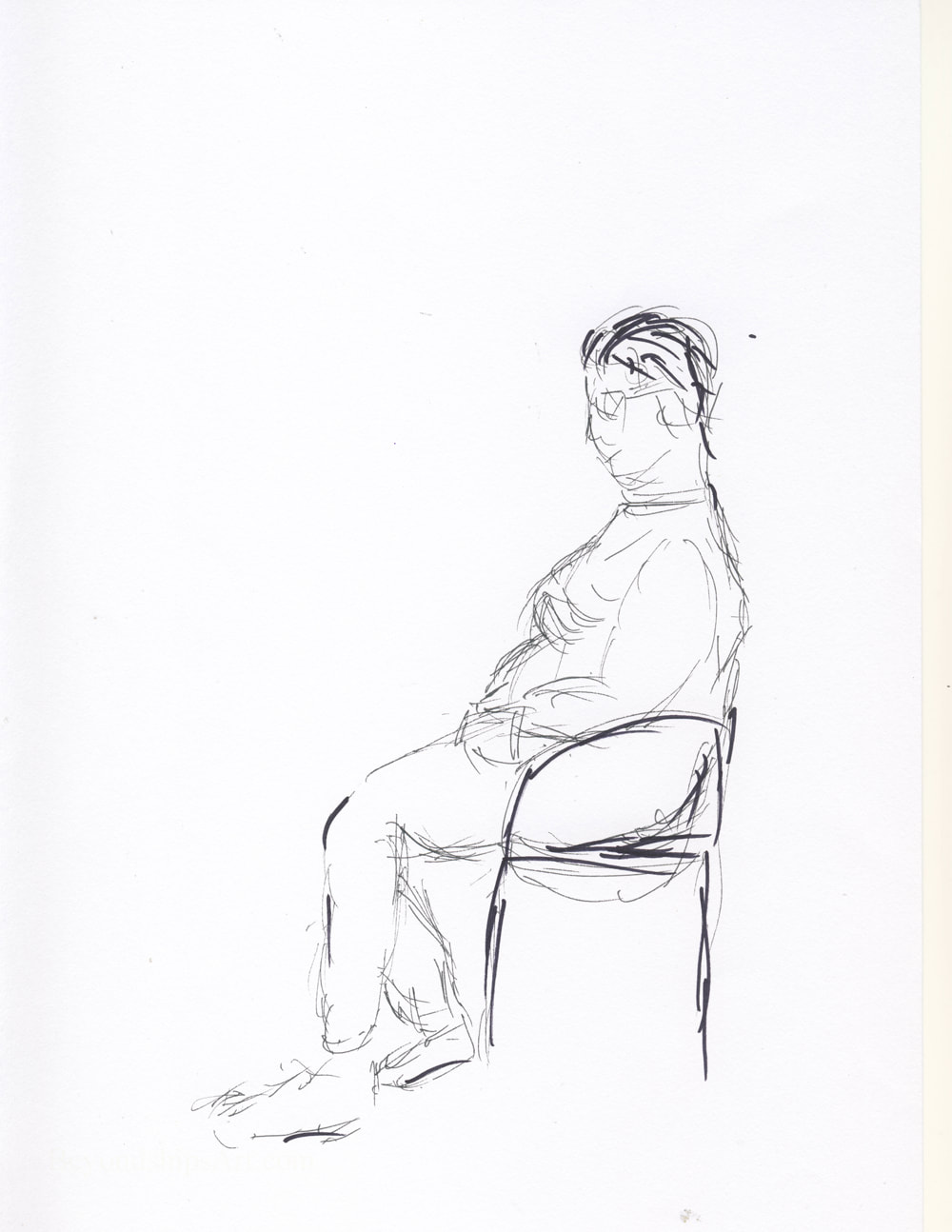

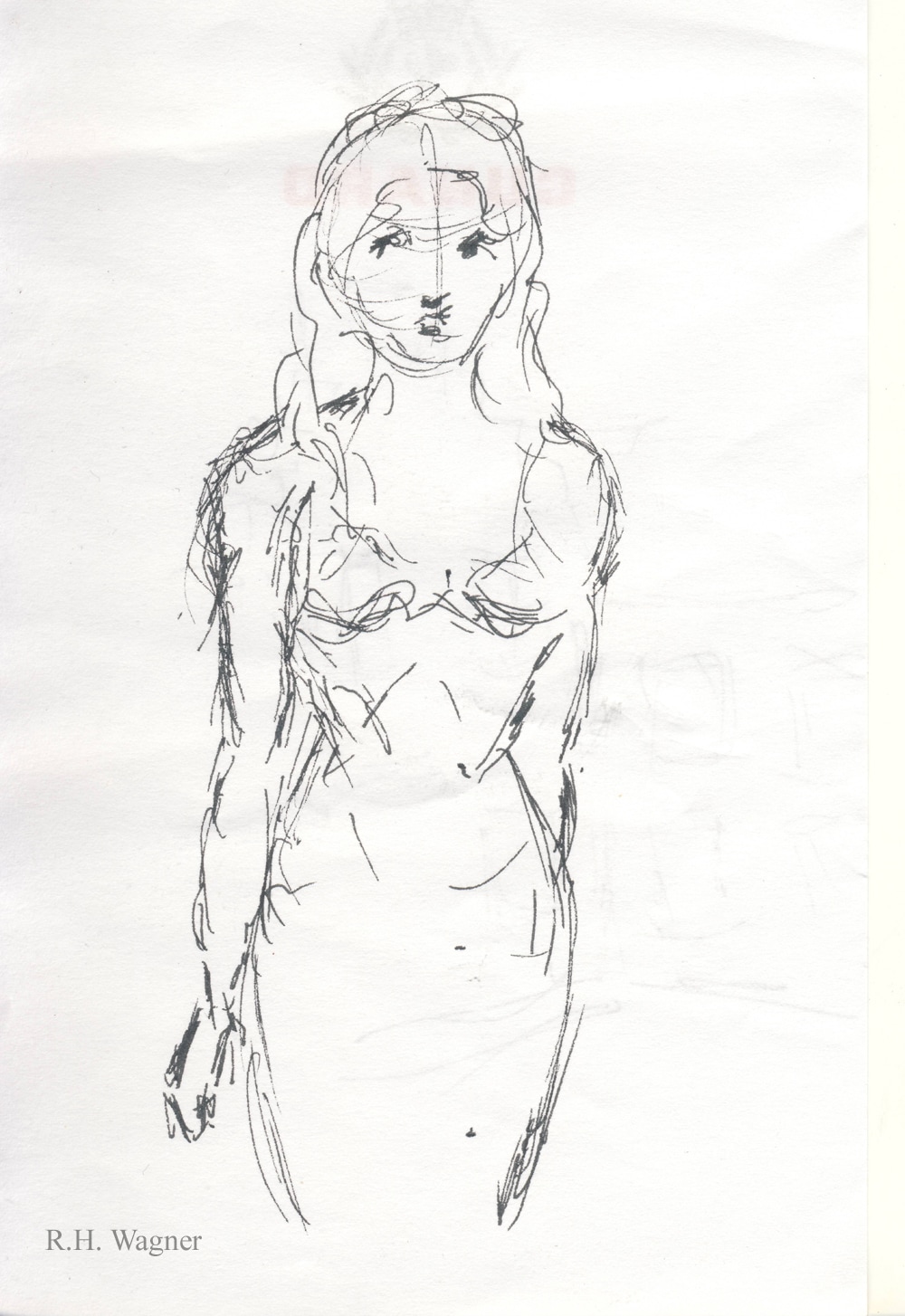

I recently participated in a painting class on Norwegian Breakaway. Entitled Canvas By U, these classes are part of the entertainment programming throughout the Norwegian Cruise Line fleet. These painting classes are a popular activity. Guests must sign up beforehand for a class. This is done via a list in the ship's library. The daily program announces the time when the list will open. On the voyage that I was on, the sign-ups began as soon as the staff member in charge of the library arrived in the morning. Within a few minutes, all of the places are usually filled despite the $35 per class fee.. There are only a dozen or so places for each class. I was told that to have more places would dilute the experience as the instructor would not be able to give enough time to each participant. The number of classes held on each cruise varies. Typically, the classes are held on days when the ship is at sea. Therefore, as a general rule, the more sea days on a given cruise, the greater the number of classes. However, the art classes have to compete with other activities for space and staff so it is not automatic that there will be a class on every sea day. Rather than having professional artists teach the classes, Breakaway uses members of the ship's activities staff who have received training in how to present these classes. While their knowledge of art technique may be limited, they are experienced in working with people and in making activities enjoyable. An effort is made to assign the classes to members of the activities staff who have an interest in art but the instructor for any given class could be any member of the activities staff. The class I attended was held in the Headliners comedy club. Two rows of tables with easels and blank canvases were arranged around the small stage. On the stage was a table with a similar set-up. In addition, there was an easel with a completed painting. Each participant's objective in this class was to make his or her own version of the painting displayed on the stage. The instructor emphasized that while everyone would be painting the same subject, each participant's end-product was to be his or her own painting. Therefore, everyone was encouraged to use their creativity and make whatever variations they wanted. The painting that served as the model in my class was a picture of a tropical island at sunset. It had a colorful red sky, ocean, sand and a grove of palm trees. Different paintings are used as the model for different classes. Thus, a guest could participate in several classes without repeating the same painting. The instructor took the class through the process of painting this picture step-by step. Beginning with the island, she pointed out what color(s) to use, how to mix the paint with water, and which brush to use. She then moved on to painting the sky, the sea, and finally the palm trees. To make these paintings, each participant was equipped with a tray with dollops of a half dozen (tempera) colors, two brushes and a 12 by 16 inch canvas board. In addition, each had a disposable apron and gloves. As the participants painted, the instructor moved about making suggestions and encouraging remarks. There was little conversation between the participants as each was very intent on his or her own painting. From what I could gather, most of the people participating in the class had little or no experience with painting. However, all were interested in painting and were keen to experience what it is like to create a painting. Some displayed a natural talent for painting. All seemed to display a sense of accomplishment as the class drew to a close.  “Max Ernst - Beyond Painting” at New York's Museum of Modern Art is a survey of the career of the Dada and surrealist artist including some 100 works from the Museum's collection. It is called “Beyond Painting” because of its focus on the different techniques that Ernst used in his works. Ernst was born in 1891 outside of Cologne, Germany. By the time the First World War broke out in August 1914, he had already embarked on a career as an artist. Drafted into the German army, Ernst served on both the eastern and western fronts. The war had a traumatic effect on Ernst. Indeed, Ernst wrote that he died on the day the war broke out and was resurrected on the day of the armistice. Returning to Germany, Ernst became interested in the Dada movement. The Dadaists believed that rational thought and bourgeois values had led to the war. Rejecting such thought, they were interested in exploring nonsense, irrationality and the inexplicable. In the 1920s, the Dada movement blended into Surrealism. This movement sought to resolve dreams and reality into a super-reality. It is not surprising that such movements found traction in the post-World War I era. Ernst's generation had just lived through a period where people had lived in mud trenches and at the sound of a whistle, stood up only to be mowed down in the thousands by machine guns and artillery as they tried to cross the lunar-like no man's land. In years of fighting, very little land changed hands. Meanwhile, people were living more or less normal lives a hundred miles from the front. The participants could very easily ask whether reality was rational. Ernst explored these concepts first in Germany and then in France. When World War II began, Ernst experienced more absurdity. He was imprisoned by the French as an undesirable foreigner. Shortly after his friends persuaded the government to release him, the Germans occupied France. Ernst was again arrested, this time by the Gestapo for producing “degenerate art.” Escaping to the United States, Ernst found some financial success and recognition. Nonetheless, he returned to France and continued to live there primarily from the the 1950s until his death in 1976. Many of the Dadaists and Surrealists believed that traditional art embodied the bourgeois values that they rejected. This “anti-art” thinking extended to some extent to technique. Consequently, they looked for non-traditional technique to create art. This exhibition highlights some of the different techniques used by Ernst. To illustrate, in The Gramineous Bicycle Garnished with Bells the Dappled Fire Damps and the Echinoderms Bending the Spine to Look for Caresses Ernst took a chart showing the metamorphosis of brewer's yeast cells, painted over portions of the chart with black paint and then drew in various objects. The result is an image that looks like an abstract circus performance. In To the Rendezvous of Friends (The Friends Become Flowers, Snakes, and Frogs), Ernst made use of grattage. He built up layers of paint and then used hard-edged tools like spatulas and palette knives, to expose the underlying layers of paint and to create surface textures. Ernst used decalcomania to produce the underlayers in Napoleon in the Wildreness. In this process, pigment is applied to a sheet of glass and then pressed onto the canvas. The squeezed pigment makes shapes on the canvas. Ernst then painted figures onto the canvas. There is also a series of sheets in which Ernst used frattage (rubbings) to produce very realistic images. He then added various details to develop the images into something more surreal. Ernst was also a sculptor and the exhibit has several works where Ernst took everyday objects and re-arranged them to create fantastic creatures. Not abandoning traditional technique altogether, the exhibit includes several oil paintings. We see here that Ernst was a very good draftsman. But as in Woman, Old Man, and Flower, the scene has a hallucinatory quality, detailed yet full of the unexpected. Certainly, the spotlight on technique in this exhibit is of interest to people who make art. However, it also provides a view into the creative process that should be of interest to all.  Several people have asked me to explain what I mean by “essential line drawing” as used on this website and in various postings that I have made on social media. Essential line drawing is a term that I use to describe a type of drawing that I have been doing for many years now. I doubt that it is in any art dictionary but it is a handy way of describing this type of drawing. Distilled to its essence, essential line drawing seeks to produce an image with the minimum number of lines that are needed to convey the concept that the artist is trying to express. For example, in a portrait, the image would be the minimum number of lines needed to convey the essence of the sitter. In a scene, it could be to the lines needed to express the emotions of the moment. This is not meant to be an academic exercise. The objectives are simplicity and clarity. You are putting aside what is non-essential in order to allow that is essential to show through more clearly. There are examples of essential line drawing in the works of many famous artists. Papblo Picasso and Henri Matisse did essential line drawings. More recently, you can find examples in the works of Peter Max. Each of these artists had their own approach but the basic concept is the same. The end result often sits on the border between realism and abstraction. You can tell what the image is but it is far from being a photographic image. From a techncal perspective, the biggest difficulty often is doing too much. If you put in too many lines, it becomes a standard line drawing. More importantly, they obscure the concept. Again, the objectives are simplicity and clarity. This is not to say that the essential line approach is the only way to produce art. It is simply one approach that I use. There are examples of essential line portraits and essential line figure drawings on Beyondships Art.

“Constable and McTaggart: A Meeting of Two Masterpieces” at the National Gallery of Scotland is a small exhibit that provides insight into the evolution of art. John Constable was one of the great English landscapes. Born in 1776 into a wealthy merchant family, Constable intially struggled for success but by the end of his life, he had become a member of the Royal Academy and had achieved fame in Britain and in Europe. The paintings that established Constable's reputation during his lifetime are polished works that follow in the tradition of the old masters. His inspirations included works by Claude Lorrain and Peter Paul Ruebens. However, distinguishing Constable's works from traditional landscapes was considerable emotion. “Painting is but another work for feeling.” Some of Constable's most successful works were monumental paintings that he called “six footers.” These monumental works have impact not just because of their size but because of the aforementioned emotion that Constable put into his works. His last six-footer “Salisbury Cathedral From the Meadow” (1831) is on display at the exhibit. The cathedral is seen in the distance with dark storm clouds surrounding it. While Constable disdained the traditional practice of altering nature to create an ideal landscape, he has added a rainbow that is not in the preparatory studies for the painting. Hope for the future after the passing storm. In preparation for the paintings he exhibited, Constable would do oil sketches. These paintings are much more impressionistic with bold expressive strokes. They were never meant for sale or public display but rather were meant to be references, memorializing a particular scene or a cloud formation etc., for use in a future more polished work. As a result, the oil sketches were not exhibited until after Constable's death. The exhibit contains several of these oil sketches. William McTaggart was also a landscape painter. He is sometimes called the “Scottish Impressionist.” Born in 1835, McTaggart was a generation or so after Constable. Nonetheless, he was greatly inspired by Constable. Constable's influence on McTaggart can clearly be seen in the exhibit. For example, McTaggart's “The Storm” is a monumental work of the size of Constable's “Salisbury Cathedral.” However, the style of the work is similar to the style of Constable's oil sketches with loose expressive brush strokes and impressionistic vagueness. Like Constable's, McTaggart's works are full of emotion. The exhibit thus shows how an idea developed as a tool by an artist in one generation can be carried forward in a later generation to become the final end product. This week, I wanted to talk about Claude Moent's “Bathers at La Grenouillere.” which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London.

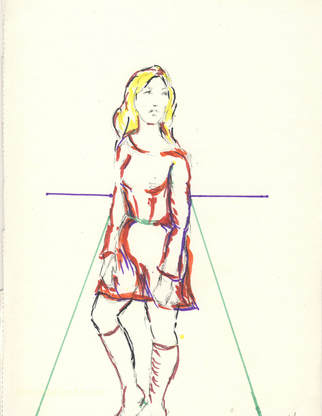

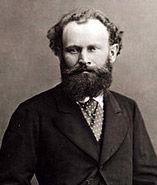

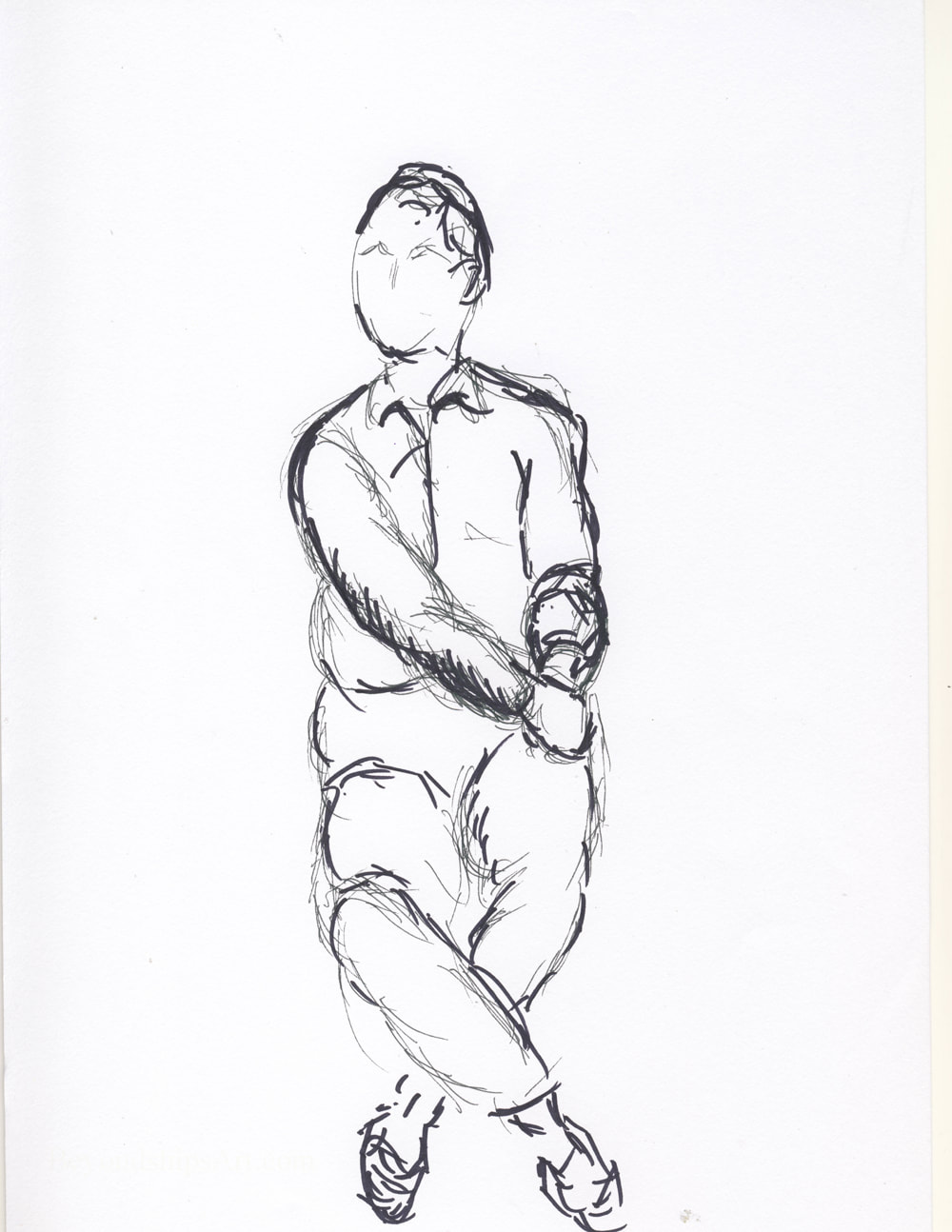

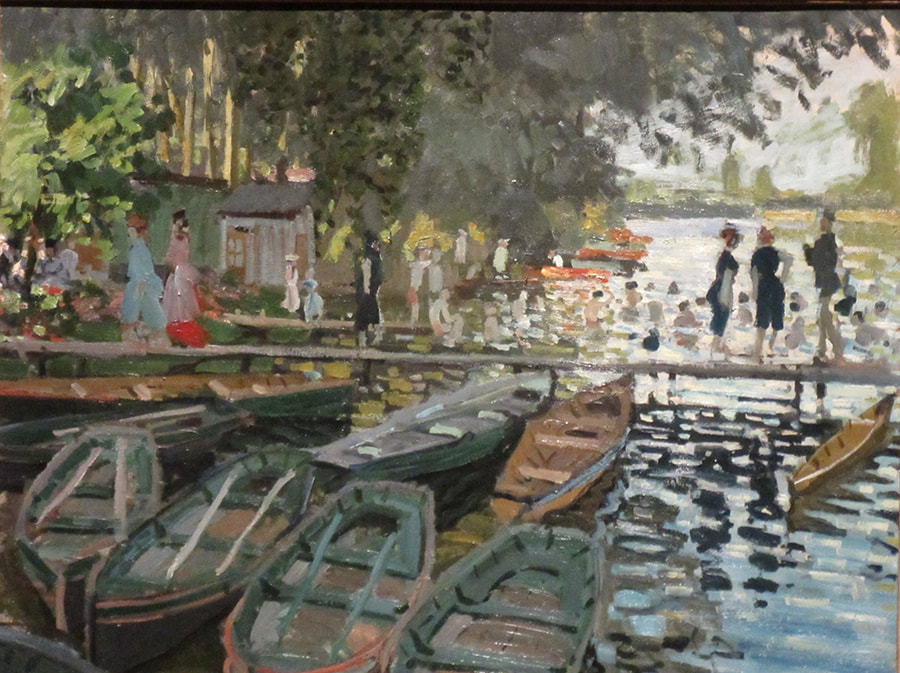

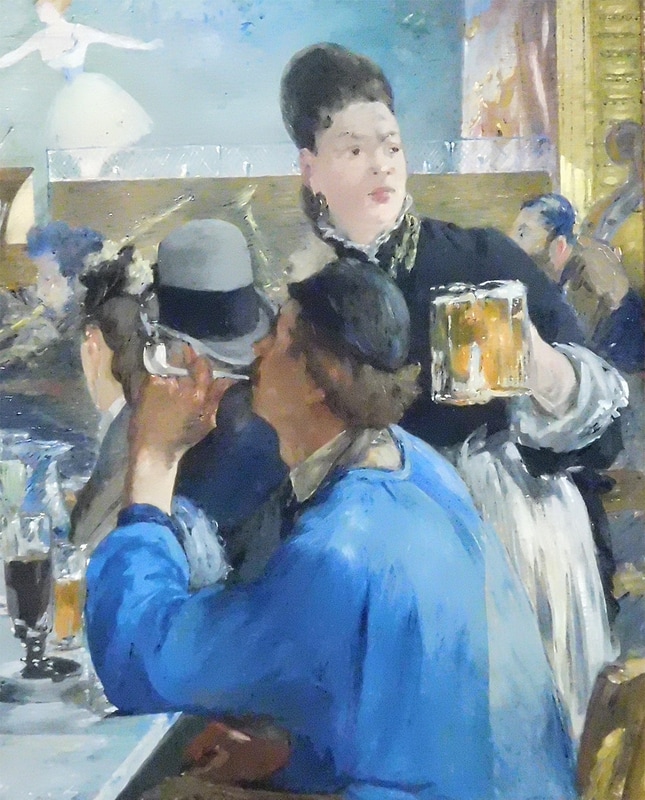

Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840. His father was a small businessman and the family moved to Le Harve about five years later so that his father could join a wholesale grocery firm that was owned by family members. Thus, Monet came from a middle class background. From an early age, Claude displayed a talent for drawing. Over time, he developed a reputation in Le Harve for his comic drawings and caricatures and was able to derive income from the sale of such works. With such a beginning, one might well expect that Monet would have developed into a portrait painter. However, one day when he went out to watch Eugene Boudin work on a landscape, he realized that landscapes were what he wanted to paint. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.” Friends and family recognized that Monet had talent. However, they were unanimous in saying that he needed to refine that talent by studying in the studio of an established artist. At that time, the most respected artists produced highly polished works with extensive modeling and glazing. The apex of the art world was history painting in which figures were depicted in scenes that told a story. Every artist's ambition was to have a work shown at the prestigious Salon in Paris. Monet was quite independent and bridled against such suggestions. Nonetheless, he went to Paris to study first at the Academie Suisse and later at the studio of Charles Gleyre, an established conventional artist. He did not like the conventional approach to the study of art. Although he often completed works in the studio, Monet preferred to work outdoors, painting directly from nature. However, his time in Gleyre's studio was not wasted because there he met Frederic Bazille and Pierre Auguste Renoir, who would be his compatriots in the Impressionist movement. Despite his dislike of conventional painting, Monet prepared and submitted several works to the Salon during this period. Most were genre paintings depicting contemporary people outdoors. In some respects, these works were reminiscent of Edourard Manet's work, Manet being something of a hero to Monet and his friends. They were more polished and the colors more subdued than Monet's later works. Nonetheless, the Salon rejected Monet's submissions. In the eyes of the juries, the works were unfinished and they failed to tell a story. During these years, Monet was able to sell some paintings but he often spent more than he earned.. Subsidies, first from his aunt and later by Bazille enabled him to continue on as an artist. In 1869, Monet moved with his mistress and young son to a cottage in Saint-Michel near Paris. Renoir was living with his parents nearby and so the two painters would often go out and paint the same subjects together. One of the places they were was La Grenouillere (the Frog Pond) a floating restaurant on the Seine at Bougival. The cafe was attached to a small island and to the riverbank by pontoons. There was a place to moor boats and a place for swimming. It was a very popular venue for socializing and summer fun. Indeed, it achieved such a reputation that Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugene came to have a look. Bathers at La Grenouiller is one of a series of studies Monet made in preparation for a larger more polished work that Monet submitted to the Salon. The larger work was rejected and later lost during World War II. What makes Bathers particularly interesting is that it is a forerunner of the style Monet would use in his later works when he was no longer working with the idea of submitting paintings to the Salon. The artist used color rather than lines to create the image. Figures, water, foliage are all described with a few bold brush strokes. The composition has a snapshot quality - - a scene of everyday life. Monet does not comment on the scene. He does not condemn it as people having frivolous fun nor does he praise it as welcome relief for the everyday worker. He just presents the scene and the viewer can make up his or her own mind. The picture can be dived into four quadrants with the pier dividing the picture horizontally and a vertical line right of center descending from the trees past the boats. Each section is a separate picture. However, the S curve of the river brings the composition together. A painting such as the Bathers would not have been possible only a few years before. The invention of the paint tube in the 1840s enabled Monet to easily transport his palette to the scene. Similarly, the invention of the metal ferrule made flat brushes possible. Such brushes enable Monet to work quickly and their use is documented by the flat brush strokes in this painting. The lesson here being that artists should not be afraid of employing new technology.  This week, I thought I would talk about Edouard Manet's Corner of a Cafe Concert, a painting which I saw in the National Gallery in London. I like Manet's work not just because it is pleasing to the eye but because it conveys emotion. I particularly like his ability to make faces thought provoking. Edouard Manet was a French artist born in 1832 in Paris. His father was a successful jurist while his mother was the daughter of a diplomat. His parents wanted him to enter one of the respectable professions rather than pursue his love of art. It was not until after Manet had failed his entrance exams for the naval academy that his family relented and allowed him to study art. While his family's resistance to his desired career must have been emotionally difficult for the young Manet, his family background provided a firm foundation for his art. Because he was financially secure, he was able to travel around Europe to view the works of past masters and to avoid starvation in the process of establishing himself as a successful artist. Manet was a man of contrasts and contradictions. He is widely acknowledged as setting art on a new course and has been called the first modern artist. Yet, he was influenced by and drew from traditional artists such as Velazquez and Goya. He scandalized the art establishment of the day by submitting works such as Dejuner sur iHerbe and Olympia to the Salon but accepted the honors of the establishment such as a medal from the Salon as well as the Legion of Honor. He was a friend of the Impressionists and influenced their work but rejected their invitations to exhibit with them preferring instead to try to have his works accepted by the Salon. An opponent of Napoleon III and a republican intellectual, Manet nonetheless joined the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War rather than flee the country as some of the artists in his circle did. Along the same lines, Manet's artistic style encompasses diverse elements. He favored broad, strong brush strokes and alla prima painting where the forms are rendered by the application of raw color rather than modeled in multiple glazed layers as was done in the popular art of the time. At the same time, his use of black paint recalls the aforementioned Spanish masters. Manet was a painter of modern life but at the same time, there are echoes of Renaissance masterpieces in his works. Corner of a Cafe Concert presents a scene of modern life. Manet enjoyed going to the Parisian cafes that were becoming popular in the 19th century and often sketched scenes that he saw there. This painting, created around 1878, is of a scene at the Brasserie de Reichshoffen. The image is not unlike a snap shot or a photo taken with an iPhone. We see people drinking and enjoying themselves while a dancer performs on stage. You can almost here the clinking of glasses, laughter and the music. In the end, however, the painting is a portrait. The central figure is a waitress who is in the process of serving mugs of beer. Hers is the only face that can be seen clearly in the picture. Something has distracted her and she is looking off beyond the bounds of the canvas. Perhaps someone is signaling her for a drink, perhaps people are arguing, or perhaps someone she knows has walked into the cafe. Whatever it is, she is lost in thought. The drinkers, conversation, the show are as irrelevant to her as she is to them. Thus, she is both at the center of the scene but at the same time not really part of the scene. The face of the waitress is quite simply done. There is very little detail or modeling. The eyes and nostrils are the most dominate and appear to be touches of burnt umber. The same color, perhaps thinned mixed with white was used in several of the other features. In her hand is a large beer mug. It too is simply done. A few strokes of white paint here and there make up the boundaries of the glass. Splashes of yellow ochre and burnt sienna depict the contents. Another thing that I noticed about this work is the use of rectangles. The upper portion of the picture - - the area framing the waitress' face - - is made up of a series of rectangles. They form the stage where the dancer who is off to the left is performing. However, these flat spaces also form an abstract design similar to those used as the subject of paintings by artists in the first half of the 20th century. Corner of a Cafe Concert was originally part of a larger work. At one point during its creation, Manet decided to cut the work in two. He then developed the two halves independently. I like knowing this because it lends a master's approval to the notion of physically altering a work. Sometimes when I am doing a picture, I reach a point where I realize that the picture as a whole does not really work. However, there are some nice bits that could work on a stand alone basis if only they had been created on their own canvas or piece of paper. What Manet has done here shows that it is perfectly permissible to cut down a work physically in order to create a picture that does work. As I have mentioned before, I often do sketches while I am commuting on a train or when I am sitting waiting for something such as a doctor's appointment. For the most part, these sketches are just for practice. However, from time to time, one is a special image that I would like to take further. The problem is that the sketches are small, pocket-size images done on a note pad or on a piece of scrap paper. Their size and the quality of the paper preclude trying to make them into a series piece of art. My solution has been the traditional one - - I hand copy the image onto a larger, better quality piece of paper. Once the image has been successfully transferred, I can add color, change it or otherwise develop the work. A problem with this method is that sometimes something gets lost in making the copy. An image can have a certain something that cannot be re-captured no matter how hard you try. A random line or two may be what gives the sketch its character. Also, hand copying can be a lot of work. This week, I tried an experiment. I took two small sketches and made high-quality digital images of them. Once you make a digital image of a work, there is a lot that you can do with it using a photo editing program such as Photoshop. You can add color, erase mistakes, improve the brightness and contrast etc. But I was not looking to digitally manipulate these sketches. Rather, my goal was to enlarge the image and then work on it by hand. Therefore, the next step was to print the images. Of course, the print will depend upon the quality of the printer. However, using my rather ancient printer, I was able to print out acceptable quality prints that could serve as the base for further development. I then used a pen to emphasize some of the lines. For color, I used colored pencils on one and Cray-pas on the other. I was pleased with the results. The size of the works was now more substantial. Also, the addition of color had enhanced the images. Clearly, there are limitations to this process. The largest paper my printer will accept is A4 so the image cannot be larger than one that would fit on that size paper. Along the same lines, he printer is probably not capable of handling heavy water color paper and the like. A better printer would push these limits out further. I don't think I will give up on hand copying. However, this little experiment has put another arrow in my quiver. Before and after. On the left side are the original images, both done on 3 x 5 inch note paper. On the right, are the images after scanning, printing and further development by hand. They are now on *.5 by 11 inch paper.

A smart phone image of a work in progress. A smart phone image of a work in progress. I find that the more I work on a picture, the less I am able to see it. No, I don't mean that my eyes become blurry. Rather, I mean that I am less able to see the picture objectively. This can lead to three problems. First, I can't see the mistakes that I have made. The eyes in a portrait can be positioned at different levels making the subject the look like something from a horror movie. Yet, what I see is something that Leonardo Da Vinci would envy. Second, I go on working even though the picture is finished. A picture can easily be ruined by overworking it. Third, I go on working on a picture even though it will never be anything worthwhile. Some pictures are just failures. There is a tendency to think, if I just make a few more changes it will be a masterpiece. However, in reality, you're just wasting your time. Better to start something new. The inability to see a work objectively occurs because the mind has a tendency to see what it wants to see. Therefore, what is needed is a fresh view of the picture. My mother, the artist Valda, used to recommend holding the picture up to a mirror. This breaks the spell and in the mirror image,you can see the work much more objectively. A technique more suited to the digital age that I often use is to take a photo of the picture with the camera in my smart phone. The objective is not to get an image that you would want to share with friends and family but rather to look at your picture in a different way. My smart phone is well-suited to this task. It takes a serviceable image in almost any light. In addition, I can see the image immediately on the phone's display screen. I often end up taking several pictures as I work. Having used the smart hone to detect a problem, I endeavor to correct the problem on the original picture. Another photo tells me whether I really have solved the problem and whether there are other problems that need correcting. The only problem that I have found with this technique is that it can use up the storage on the smart phone. Therefore, it is best to delete the images as you go along.  Rembrandt, Self Portrait (Image public domain Wikimedia Common) Rembrandt, Self Portrait (Image public domain Wikimedia Common) Portraiture isn't just about capturing a likeness. A good portrait communicates something about the person who is the subject matter of the work. I have always liked the work of the English portrait artist Sir Thomas Lawrence. Many of his subjects were famous people such as the Duke of Wellington but that is not what makes the works interesting. A look in the eyes, the smile, the position of the body reveal something about Lawrence's people even the ones who history has forgotten. You feel like you would have liked to have met them. Along the same lines, this is why most portraits done by sidewalk artists are disappointing. Many are great technically. However, in most cases, the artist is merely producing a likeness without seeking to know or understand the person who is the subject. Since portraiture can (and should) be a way of communicating something about the person who is the subject of the work, it can be a means of self-analysis. In order to say something about a subject, you need to understand how you feel about that subject. The classic example of self-analysis through portraiture is the self-portrait. A good self-portrait reveals how the artist sees himself or herself. Rembrandt did self-portraits throughout his life. As a result, we can see him proud and self-confident at the height of his success as well as melancholy and thoughtful after fortune had turned against him. Towards the end of her life, my mother, the artist Valda, embarked on a series of works chronicling the important moments in her life. Inherent in this project was coming to an understanding about which moments were significant to her. Unfortunately, Valda was only able to produce a few works in this series before she became too ill to work. Inspired by Valda's project, I began my own slightly different project a few years ago. The idea was to do a series of pictures of people with whom I had had significant relationships. I wanted to understand what made those relationships significant, what had happened in those relationships and my feelings toward the people involved. The first step in the project was deciding which relationships were significant. I had in my mind a general idea of the importance of my various relationships but as I began to do the pictures, I realized that some were not really as important as I had thought. Eventually, I came down to four who were game-changers in the sense that I was never the same afterward. I have probably done more than a hundred pictures on this project. For some, I based the image on photographs but most were done from memory. They have ranged from paintings to quick sketches on pieces of scrap paper. In doing the pictures, I have thought about what happened and why. But more importantly, I examined my feelings both then and now. Overall, it has been a worthwhile project. I have a much better understanding of how I got where I am in life. At the same time, I have come to realize that this is an ongoing project perhaps without end because my feelings towards the past change. It has also produced some successful artwork. I participated in an exhibition over the winter in which I showed one of the works from this series. A stranger attending the exhibition spent quite a long time in front of that picture. He then came up to me and said that he liked the picture. “I would like to have met her. You must have really loved her.” While the picture has its technical faults, it must be a good portrait as it successfully conveyed the feelings of the artist. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed