|

Click here for our review of "Progressive Revolution:Modern Art For A New India" at the Asia Society Museum in New York City.

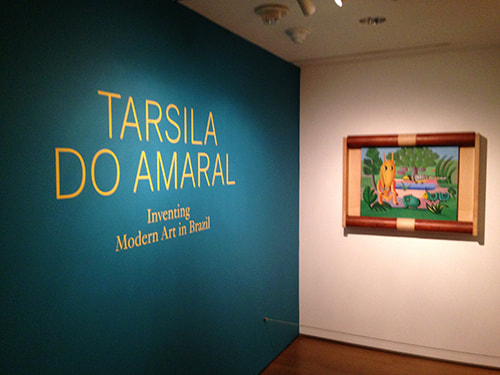

“Leon Golub Raw Nerve” at the Met Breuer in New York City is a selective survey of the work of the 20th century American artist Leon Golub. Born in Chicago in 1922, Golub studied art history at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1942. After the Second World War, he studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. There he met his wife, the artist Nancy Spero, to whom he was married for nearly 50 years. The two arists lived in Europe for periods during the 1950s and 1960s. While there, Golub developed his interest in 19th century historical painting and artists such as Jacques Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He was also interested in ancient Greek and Roman art. As a result, at a time when the art establishment was only interested in abstraction, Golub was creating art in which recognizable human figures were central. Golub, however, was not a conventional artist. While the influences of ancient and traditional art can be seen in his works, he also incorporated much of the force of the abstract expressionist painters. His images were often done with free broad strokes. He added layers of paint and then scraped them away. He left sections of the canvas in its raw state. This technique did not make for pretty pictures but it did make them emotionally powerful. When Golub and Spero returned to the United States in the 1960s, opposition to the Vietnam War was growing as that conflict escalated. Golub became involved in the anti-war movement and violence and cruelty became themes in his art. Other social and political issues such as racial inequality, torture, oppression and political corruption would also draw Golub's attention throughout the rest of his career. An artist seeking to convey a political or social message with a work of art has to be careful to avoid making the work dependent upon the viewer's knowledge of the underlying political or social issue. A scene or a symbol that everyone today would recognize as having a certain meaning may not mean anything to a viewer 20 years from now. Thus, a work that is too heavily dependent upon today's headlines may have no meaning in the future. Golub's works transcend the headlines. For example, “Gigantomachy II' is a monumental painting of a group of muscular male figures fighting, which was done during the Vietnam War. The title refers to a battle between the Olympian gods and a race of giants and the painting recalls an ancient Greek frieze. However, it is not a glorious depiction of battle but rather conveys a sense of cruelty and pain. Thus, it is not just about ending the Vietnam War but is a condemnation of war that continues to have meaning. Along the same lines, in “Two Black Women and a White Man,” Golub presents two black women sitting on a bench with a white man leaning against a wall behind them. Perhaps, it is a group waiting for a bus. However, the positioning of the figures and the way they are avoiding any interaction, underscores the separation and isolation of the races. The scene could be in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement or in South Africa during Apartheid, it could be now. The message of the picture still comes through.  "The Long Run” at New York's Museum of Modern Art is an exhibition encompassing works by nearly 50 artists who were active in modern art during the second half of the 20th century. The artists include numerous famous names such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichenstein, Andy Warhol and Georgia O'Keefe. The works exhibited are examples of work done later in these artists' careers. Rejecting the notion that innovation in art is “a singular event—a bolt of lightning that strikes once and forever changes what follows,” the exhibit seeks to show that “invention results from sustained critical thinking, persistent observation, and countless hours in the studio.” The exhibit seeks to illustrate its thesis by presenting works that show the evolution of the artists' works past the time when they were first recognized. One cannot seriously debate the exhibit's thesis. The notion of an artist being struck with a bolt from the blue that leads to a new direction in art is more the stuff of Hollywood drams than reality. As in other siciplines, artists develop their thoughts over time. Skills are refined and new materials are encountered that enable the artist to do new and/or different things, At the same time, personal relationships may be changing, new associations formed and events in the outside world may occur that influence the artist's thinking. Not only is there an evolutionary trail leading up to an artistic breakthrough but there is a trail after that breakthrough. The exhibit shows that artists evolve in different ways. Some artists make radical changes in style. For example, in 1969, Phillip Guston abandoned the abstract style that he had been known for in favor of a more figurative style. He said that he needed to make this change in order to enable him to address the political and social issues of the day. Other artists continue on in the same vein that first brought them recognition. For example, Andy Warhol's black and white drawing of Da Vinci's Last Supper with various colored consumer product logos superimposed makes essentially the same point as his earlier paintings of Campbell's Soup cans, i.e., the commercialization of western society. Along the same lines, Roy Lichenstein's “Interior with Mobile” is similar in style to his earlier comic strip inspired works. Even for those artists who stayed close to their original style, the exhibit makes the point that these artists went on working throughout their lives. In some cases, the later works may not have be as important to the history of art as their earlier works but these artists continued to produce vibrant and worthwhile art. Leaving aside the thesis of the exhibit, the Long Run is still an enjoyable exhibit. It brings together numerous examples of good modern art. This includes lesser known examples by major artists that deserve to be brought to the public's attention. “Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil” at the Museum of Modern Art presents the work of the artist who led the development of the modernist movement in Brazil. During the 1920s, Tarsila, as she is widely known in Brazil, developed a distinctive style that was truly Brazilian. MOMA has assembled over 100 works drawn from various collections including some of her landmark paintings to document this development.

Tarsila was born in Capivari, a small town near Sao Paulo, Brazil in 1886. Her family owned coffee plantations. Although it was unusual at that time for girls from affluent families to pursue higher education, Tarsilia was allowed to pursue her interest in art, both in Brazil and in Barcelona, Spain. Her instructors were conservative, academic artists. In 1920, after the end of her first marriage, Tarsila went to Paris in 1920 to study at the prestigious Academie Julian. Her studies were again in the academic tradition. Meanwhile, a modern art movement had taken root in Brazil. The landmark Semana de Arte Moderna was a festival that called for an end to academic art. Upon Tarsila's return to Brazil, she discovered modern art became a leader in this movement, one of the five artists and writers in the Grupo dos Cincos. In 1922, she returned to Paris and studied with several Cubist artists including Ferdinand Leger and Andre Lehote. However, she continued to think in terms of Brazil. She painted “A Negra,” an abstract portrait of an Afro-Brazilian woman. Returning to Brazil, she embarked upon a tour around the country. The drawings of the countryside and everyday life she made while on this journey served as inspiration for later paintings. Her traveling companion was the writer Oswald de Andrade wrote a manifesto “Pau-Brasil” calling for truly Brazilian culture. She married Andrade in 1926. Tarsila made another journey to Paris in 1928 where she came into contact with surrealist art. (It should be noted that Tarsila did not live like a starving artist in Paris. A renown beauty from a wealthy family, she lived a lavish lifestyle, mixing with famous personalities, artists, writers and intellectuals). That same year, she painted “Abaporu” (the man who eats human flesh) as a birthday present for her husband. He used the image for the cover of his “Manifesto of Anthropology,” which called upon artists to cannibalize European culture and other influences in order to create a distinctive Brazilian culture. The painting and the manifesto are considered landmarks in the development of Brazilian culture. Tarsila's family fortune was all but lost as a result of The New York Stock Exchange crash of 1929 and the following Depression. Her marriage to Andrade ended the following year. In 1931, Tarsila traveled to Moscow with her new boyfriend, a communist doctor. There she was influenced by Socialist Realism. Her subsequent work was primarily concerned with social issues. The exhibition at MOMA focuses on the decade beginning with her journey to Paris in 1920. It demonstrates how Tarsila's work evolved incorporating over time elements of Cubism, Brazilian folk art and Surrealism while retaining her own style. Although she was influenced by each of these schools, she did not become part of them. Hers is a distinctive style: flat two dimensional; populated with simplified, distorted figures and landscapes; often with geometric backgrounds. It is also clearly Brazilian, not only in the choice of subject matter but in the selection of colors. In short, it is what Andrade was calling for - - a synthesis of a number of influences producing a truly Brazilian art. The exhibit also includes some works after her trip to Russia. “The Workers” (1933) was one of the first paintings in Brazil dealing with social issues. It reflects the influence of Soviet painting both in subject matter and palette. Incorporation of this soulless style was not a happy addition to Tarsila's arsenal. The work does not have the life of her earlier works and the treatment of the subject matter is much like what numerous other artists were doing at the time. However, it does serve to spotlight how special her work was during the preceding decade. This week, we take a look at the art collection on the cruise ship Celebrity Reflection. Celebrity Cruises has been collecting art and displaying art on its ships since its founding. Credit for beginning the Celebrity Art Collection in the 1990s is usually give to Christina Chandris, wife of John Chrandis then the owner of Celebrity Cruises. The line has since been purchased by Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. but the tradition of having an art collection aboard the ships continues. Responsibility for assembling the art collection on Celebrity Reflection, which entered service in 2012, was given to a firm called International Corporate Art. As when Ms. Chandris began the collection, the works on Celebrity Reflection are contemporary. They are primarily conceptual with much use of photographic images and non-traditional materials. There is almost no use of traditional techniques such as drawing or painting. The collection is prominently displayed. Indeed, there are several large installations that occupy considerable space. The works on the forward and aft stair towers are beautifully lit and dominate the landings. Clearly, the art collection was not an after thought. Since the name of the ship is Reflection, the theme of the collection is “the seductiveness of reflection.” The term “reflection” is meant both in the literal sense of surfaces that reflect light and in the metaphysical sense of thinking (reflecting) on a topic. If you look for this theme in the works, you can find it but it is not really vital to appreciating these works. Next to each work is a plaque discussing the work. These tend to be somewhat enthusiastic, using strings of adjectives and phrases which meld together to become rather meaningless. They obscure rather than clarify but that is often the case with the art establishment. Good art does not require verbose explanations. Each of Celebrity's Solstice class ships has a living tree suspended in the central atrium. On Reflection, this centerpiece was designed by Bert Rodriguez. The tree grows upward out of a shiny metallic basin. On the bottom of the basin is an aluminum tree pointing downwards. In other words, the aluminum tree is like a reelection of the living tree. However, unlike the living tree, the man-made tree is without leaves, only colorless electric lights adorn its branches. Another major installation is located by the specialty restaurants. On either side of the corridor are large photographic images from a forest. However, each of the trees has been perforated with reflective materials in each of the holes. Thus, you can glimpse your image moving through the forest as you pass by. It is visually impressive. The artist was Albano Afonso. Not far away is another installation, the Celestial Garden by Carlos Betancourt in collaboration with Alberto Latorre.. Colorful flowers contrast cover the walls, ceiling and floor, set against dark, nearly black backgrounds. Quite pretty. A shiny, abstract-shaped bench provides the reflective element. Of the works in the stairtowers, I found the photographic images by Miranda Lictenstein the most appealing. She manipulates the images so that they become essentially unrecognizable forming abstract designs. Her choice of pastel, natural colors in these images, however, makes them attractive. I was also impressed by the life-size silhouette at the top of this same tower, a photographic image by Yuki Onodera. The sparkling lights on the woman's dress are actually fragments of other photographic images. I did not find everything in the Celebrity Reflection collection appealing. However, I did find the collection thought provoking. I could not dismiss any of the works out of hand. Rather, I had to think about why I did not like a particular work. Causing viewers to think is a hallmark of a good collection. Above left: "Untitled #2", "Untitled #4" and Untitled #7" by Miranda Lichtenstein in the aft stair tower.

Above right: An installation by Albano Afonso.  Louise Bourgeois is best known for her giant sculptures of spiders. However, as seen in “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait” at New York's Museum of Modern Art, there was more to Bourgeois' work than spiders. Bourgeois was born in 1911 in Paris, France. Her family operated a gallery that sold tapestries where they all worked. The father concentrated on the commercial aspects of the business while her mother, with Louise's assistance, worked on restoring the tapestries. It was not a happy family. Her father was a philanderer and abused Louise. Her mother ignored her father's infidelities and focused on providing a nurturing environment for her children. The emotions Louise experienced then were to influenced her art throughout her career. Indeed, her spider sculptures were a tribute to her mother reflecting qualities of reliability, protection and industriousness. After her mother's death, Bourgeois began to study art in 1930s Paris. She also came into contact with many of the artists working in Paris at that time including the Surrealists. To help generate some income, she opened a print shop next to the family tapestry gallery. There she met American art historian Robert Goldwater. They were married in 1938 and moved to New York City. In America, Bourgeois studied at the Art Students League of New York. During this period, the League was an artistic epicenter where important artists and artists who would soon become important congregated both as teachers and students. Through the League and her husband's contacts, she came into contact with people such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning. At the same time, Bourgeois' work was becoming recognized. By 1982, she was so established that she had her first retrospective exhibit at MOMA, the first woman artist to have such an exhibition. She continued to produce art until her death in 2010. Bourgeois used her art to explore her emotions, sexuality and as a means of resolving conflicts. Thus, one can see her returning to certain topics repeatedly in her work. The exhibit has been arranged around a number of themes. For example, one theme is architecture. Bourgeois liked the stability and order of buildings - - a stark contrast to the dysfunctional environment in which she grew up. Another theme is fabric, works made from cloth. Again, this echoes back to her early days in the tapestry gallery. Although there are some sculptures in the exhibit, most of the 300 works are prints and drawings. The prints are particularly instructive. In making a print, Bourgeois would first make an image on a plate. After seeing a print the plate, she would make changes to the plate and print again. This process of printing the plate and then making changes would continue until she had the final image that she wanted to publish. Since the interim prints were saved, you can see how her thinking evolved. In addition, there is significant variety within the various series. For example, some of the prints have both black and white and color versions. The viewer can decide for himself or herself which version of the image speaks best. It is not necessarily the version selected as the final one by the artist.  “Max Ernst - Beyond Painting” at New York's Museum of Modern Art is a survey of the career of the Dada and surrealist artist including some 100 works from the Museum's collection. It is called “Beyond Painting” because of its focus on the different techniques that Ernst used in his works. Ernst was born in 1891 outside of Cologne, Germany. By the time the First World War broke out in August 1914, he had already embarked on a career as an artist. Drafted into the German army, Ernst served on both the eastern and western fronts. The war had a traumatic effect on Ernst. Indeed, Ernst wrote that he died on the day the war broke out and was resurrected on the day of the armistice. Returning to Germany, Ernst became interested in the Dada movement. The Dadaists believed that rational thought and bourgeois values had led to the war. Rejecting such thought, they were interested in exploring nonsense, irrationality and the inexplicable. In the 1920s, the Dada movement blended into Surrealism. This movement sought to resolve dreams and reality into a super-reality. It is not surprising that such movements found traction in the post-World War I era. Ernst's generation had just lived through a period where people had lived in mud trenches and at the sound of a whistle, stood up only to be mowed down in the thousands by machine guns and artillery as they tried to cross the lunar-like no man's land. In years of fighting, very little land changed hands. Meanwhile, people were living more or less normal lives a hundred miles from the front. The participants could very easily ask whether reality was rational. Ernst explored these concepts first in Germany and then in France. When World War II began, Ernst experienced more absurdity. He was imprisoned by the French as an undesirable foreigner. Shortly after his friends persuaded the government to release him, the Germans occupied France. Ernst was again arrested, this time by the Gestapo for producing “degenerate art.” Escaping to the United States, Ernst found some financial success and recognition. Nonetheless, he returned to France and continued to live there primarily from the the 1950s until his death in 1976. Many of the Dadaists and Surrealists believed that traditional art embodied the bourgeois values that they rejected. This “anti-art” thinking extended to some extent to technique. Consequently, they looked for non-traditional technique to create art. This exhibition highlights some of the different techniques used by Ernst. To illustrate, in The Gramineous Bicycle Garnished with Bells the Dappled Fire Damps and the Echinoderms Bending the Spine to Look for Caresses Ernst took a chart showing the metamorphosis of brewer's yeast cells, painted over portions of the chart with black paint and then drew in various objects. The result is an image that looks like an abstract circus performance. In To the Rendezvous of Friends (The Friends Become Flowers, Snakes, and Frogs), Ernst made use of grattage. He built up layers of paint and then used hard-edged tools like spatulas and palette knives, to expose the underlying layers of paint and to create surface textures. Ernst used decalcomania to produce the underlayers in Napoleon in the Wildreness. In this process, pigment is applied to a sheet of glass and then pressed onto the canvas. The squeezed pigment makes shapes on the canvas. Ernst then painted figures onto the canvas. There is also a series of sheets in which Ernst used frattage (rubbings) to produce very realistic images. He then added various details to develop the images into something more surreal. Ernst was also a sculptor and the exhibit has several works where Ernst took everyday objects and re-arranged them to create fantastic creatures. Not abandoning traditional technique altogether, the exhibit includes several oil paintings. We see here that Ernst was a very good draftsman. But as in Woman, Old Man, and Flower, the scene has a hallucinatory quality, detailed yet full of the unexpected. Certainly, the spotlight on technique in this exhibit is of interest to people who make art. However, it also provides a view into the creative process that should be of interest to all. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed