Matisse in the Studio at the Royal Academy of Arts presents a number of works by Henri Matisse along with various objects that are depicted in those works. Henri Matisse was born into a well-to-do merchant family Northern France in 1869. When he became an adult, he saw himself as following a career in the law. To this end, he studied law and when he obtained his qualifications, he found a position as a court administrator. It was not until after his mother gave him a set of art supplies while he was convalescing from an illness that he found art was his true calling. During his long career, Matisse's style continuously evolved as he incorporated new inspirations into his art. He began with traditional European art but along the way drew inspiration from the Impressionists, Post-impressionists, African art and Islamic art as well as from the contemporary art of the first half of the 20th century. While his works sometimes bordered on abstraction, they always held a connection to recognizable real world objects. Throughout his life, the artist collected furniture, utensils, everyday objects and works of art from several cultures that he found visually appealing. Sometimes these objects would appear in his paintings again and again. He analogized them to actors who appear in multiple plays. This exhibit brings together some of these objects along with the works in which they appear. For example, the exhibit includes two silver chocolate pots that appear in a Matisse still life. There is also an ornate Venetian chair that the artist liked to paint. At the end of the day, most of these objects are just ordinary objects. However, they are of interest for two reasons. First, they are objects that once were the possession of a great artist and thus have historical interest just as the hat that Napoleon wore at Waterloo would be of historical interest. Second, they show that a great artist can draw inspiration from an ordinary object and transform its image into something that is beyond the ordinary. Of greater interest are the works of art from other cultures that Matisse collected. Objects such as African masks and sculptures were not so much subjects of his paintings and sculptures but rather things that influenced his style. The influence of the African masks can clearly be seen in his portrait drawings. He has adopted the simplicity of line of the African artists. But, while the African works conceived for religious purposes - did not seek to depict specific individuals, Matissse captured the character of the individuals portrayed. Thus, one can see the evolution of art. Even leaving aside the juxtaposition of the objects and the works of art, this is still a good exhibit. It presents works from across the span of Matisse's career. As a result, it contains quite a few impressive works of art. With regard to the mechanics of the exhibit, there were too many people for the space. Admission was by timed-ticket, which is supposed to prevent overcrowding. Nonetheless, there were too many people in the exhibit area when we were there. The crowd made it difficult to study and appreciate the works. This was compounded by having groups of school children laying on the floor around some of the works trying to do projects related to the exhibit. You had to be careful not to step on anyone. It would have been much better both for all concerned to have had separate times for the classes and for the general public. “Calder: Hyermobility” at the Whitney Museum of American Art is an exhibit of sculptures by Alexander Calder. It focuses on the importance of motion in Calder's work.

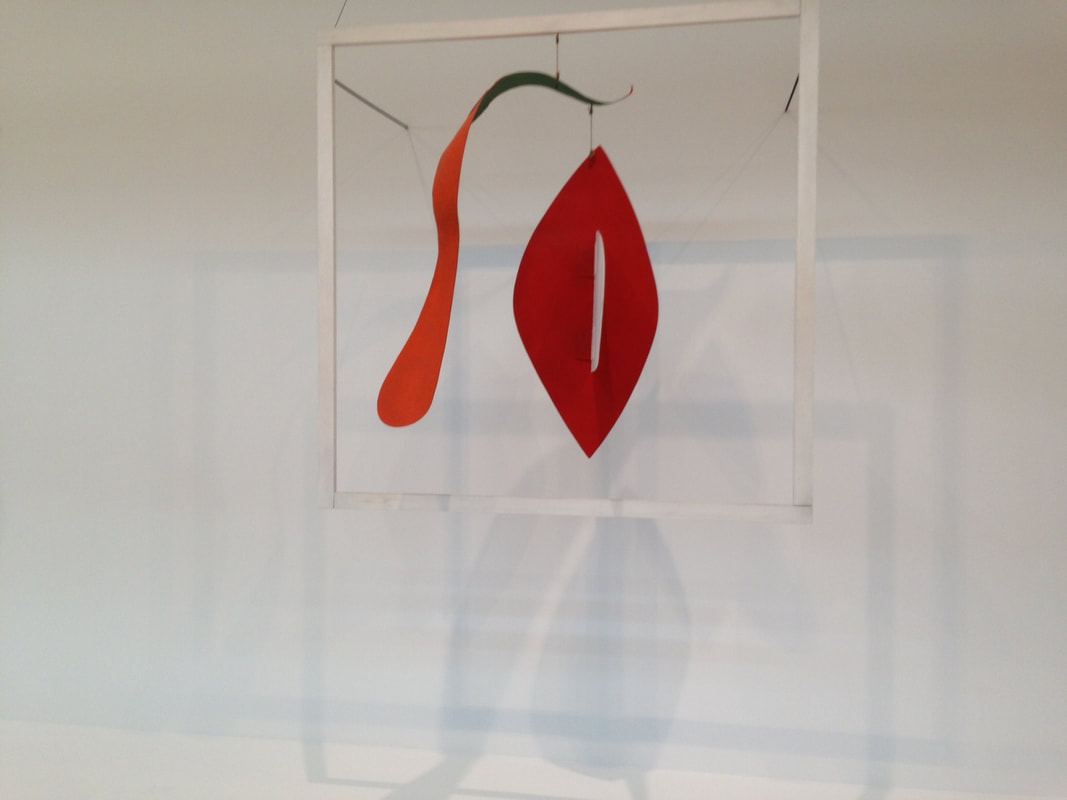

Alexander Calder came from an artistic family. His father and grandfather were both sculptors. His mother was a professional portrait painter. Not surprisingly, Calder did art work from an early age and even had studios in the basements of several of the houses that the family occupied while he was growing up. Knowing the difficulties associated with being a professional artist, his family did not encourage Calder to follow in their footsteps. Instead, he studied to be become a mechanical engineer. Following his graduation from the Stevens Institute in 1919, Calder held a variety of jobs including being a hydraulic engineer and working as a mechanic on a steam ship. Calder, however, found this work unsatisfying and decided to make art his career. To this end, he enrolled in the Art Students League in New York. In 1926, he moved to Paris where he established a studio and became friends with a number of avant garde artists. Following a visit to Piet Mondrian's studio, he decided to embrace abstract art. During this period, Calder became interested in creating sculptures with movable parts. His early works along this line moved by cranks and motors, perhaps reflecting his engineering background. By the early 1930s, Calder had returned to the United States and his works were less mechanical. Instead, the works moved either in response to touch or to the wind. Marcel Duchamp coined the term “mobiles” to describe Calder's sculptures. The Whitney exhibit includes several of Calder's mobiles. Some are freestanding while others are suspended from the ceiling. Even when they are static - - which they are most of the time - - the graceful lines and pure colors of these sculptures make them appealing. At specified times during the day, a staff member appears and “activates” some of the sculptures. Typically, this is done by giving one part of the sculpture a gentle push setting it in motion. The movement causes the image that the viewer is seeing to change. Whereas a portion of the sculpture was say pointing in one direction originally, it points in a number of different directions as it moves. As a result, the overall shape of the sculpture changes, becoming a new image. In addition to the mobiles, the Whitney has one of Calder's large static sculptures in the center of the exhibit. These Calder sculptures were dubbed “stabiles” by Jean Arp in 1932 to distinguish them from Calder's mobiles. With a stabile, the image changes as the viewer moves around the object. In this, the process is not different than traditional sculpture. However, here the forms are abstract - - graceful arches arising from seemingly delicate points. Over the last 90 years or so, the public has become familiar with abstract sculpture. However, the elegance of Calder's designs, both static and kinetic, are such as to have enduring appeal.

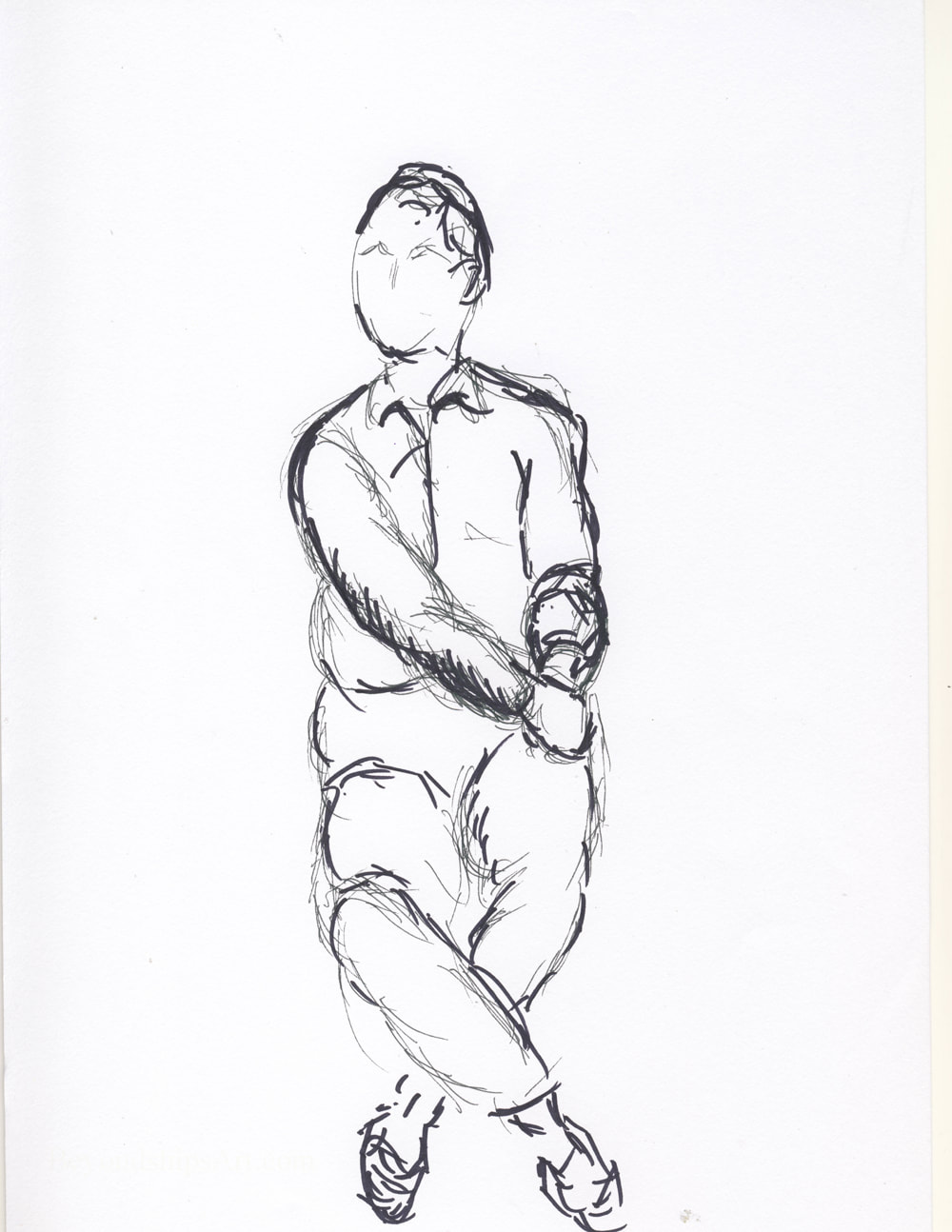

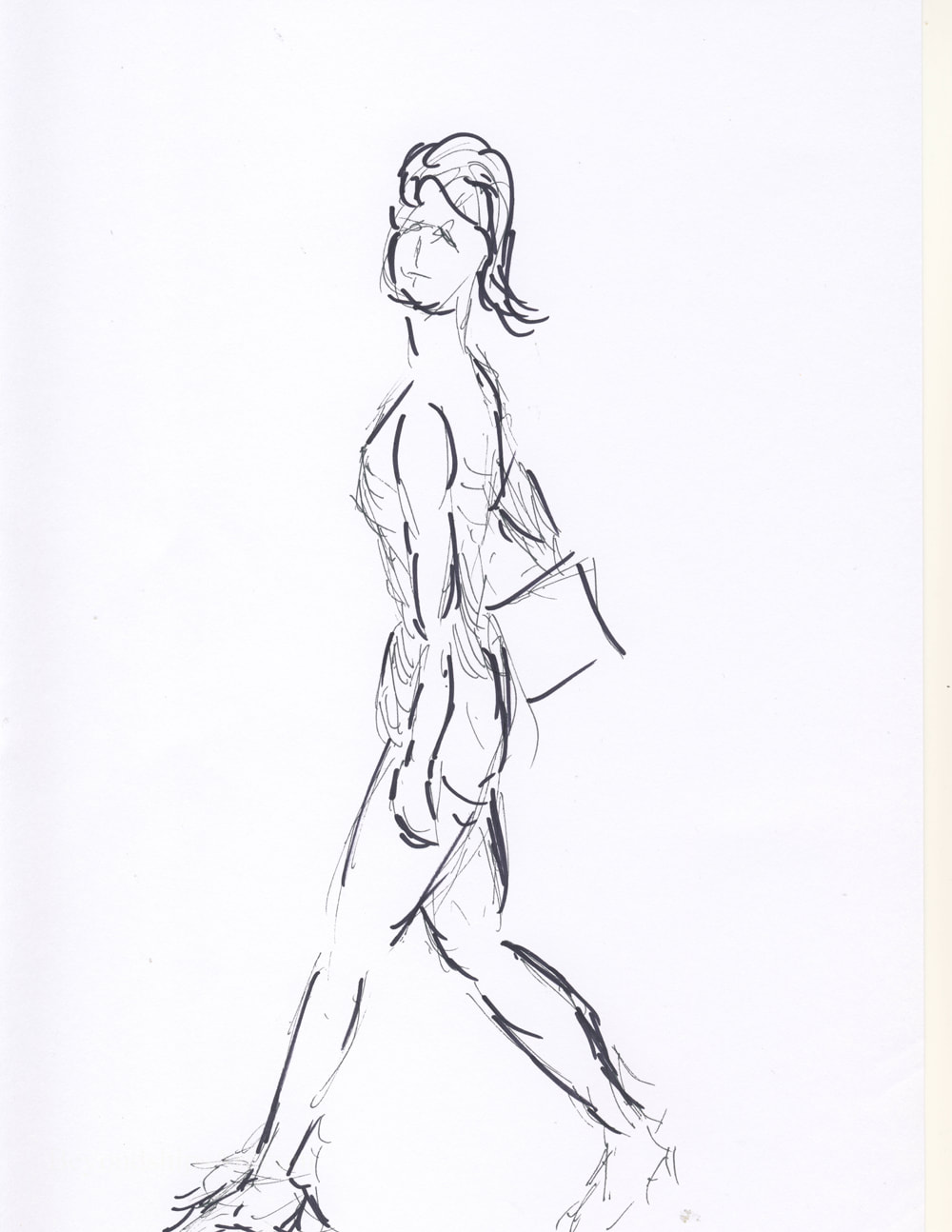

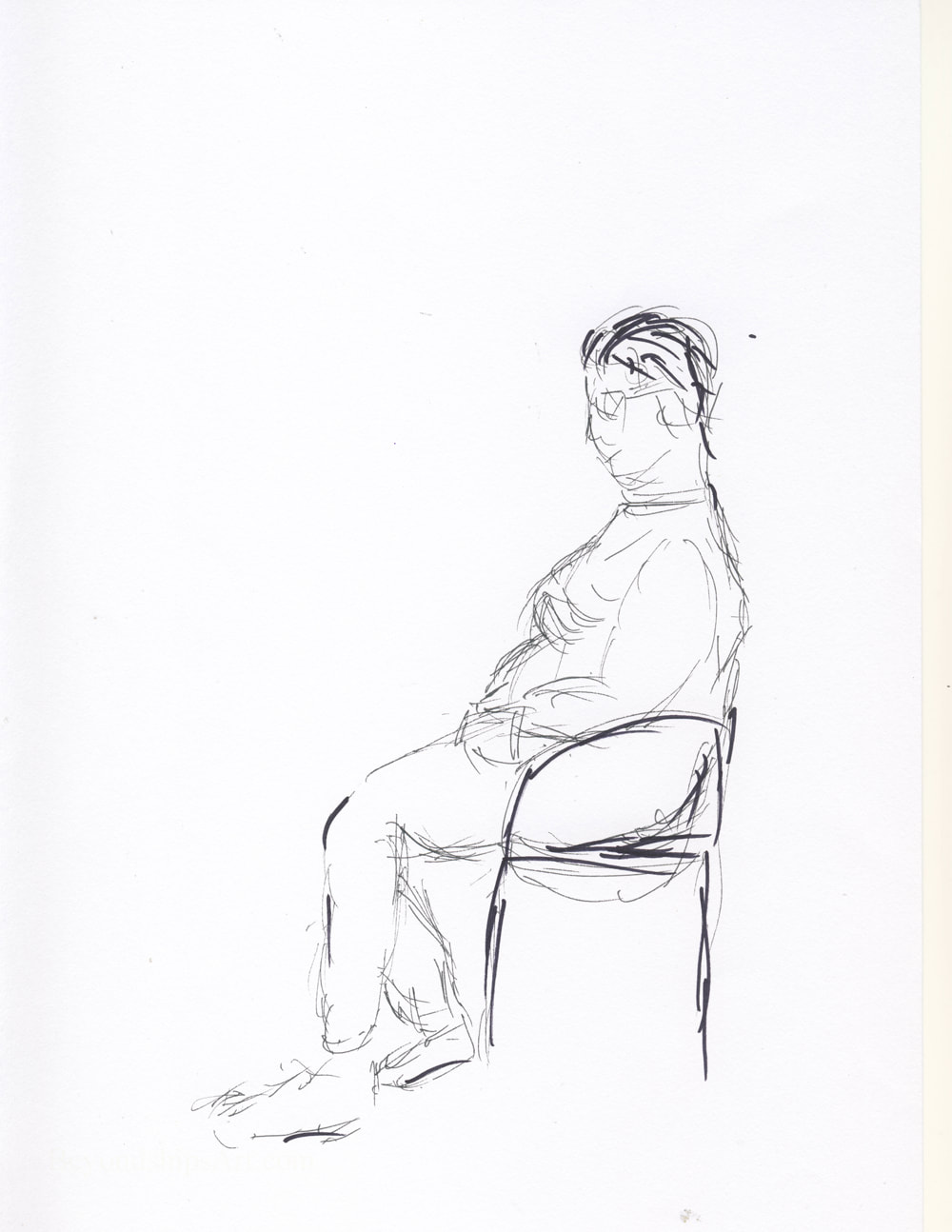

It is not unusual to find an art exhibition on a passenger ship. Most cruise ships have an art gallery that sells prints and original works of art. What is unusual is for a ship to host a preview of an art exhibit that will be seen on land in a major city. As part of its 2017 Transatlantic Fashion week, the ocean liner Queen Mary 2 held a preview of “Drawing On Style: Original Fashion Illustration.” This exhibition was a preview of a larger exhibition held at the Gray MCA Cheryl Hazon Gallery in New York City. The preview presented 21 works by 10 artists. It was held in the annex to QM2's permanent art gallery. Until fairly recently, illustration was a somewhat disparaged stepchild of fine art. In part, this was due to the fact that illustration has commercial connections. It is often used in advertising to sell a product or service. Also, illustration was often used in conjunction with a book or a story to elaborate on an idea or a point made by the author of the book or story. In such situations, it was argued that the illustration is subservient to the book or story and not a stand alone artistic concept. The old view of illustration lost ground as people came to realize that a good illustration can stand on its own without regard to the product or story it was commissioned to serve. Indeed, at this exhibit, it is hard to detect what fashion designer's conept the works were originally intended to illustrate. It s only by reading the signage that you find that a given work was done for one of the great fashion houses or a well-known fashion magazine. In other words, the works stand on their own. The works on display were drawings, often pen and ink with a brushed wash but also some graphite works and some watercolors. They were not traditional drawings. Rather, like the Mask paintings of Henri Matisse, they distill the subject matter to its essential lines. Colin McDowell, fashion commentator and one of the artists whose works were included in the exhibit, explained: “In fashion illustration, you are creating a mood, a feeling and you can do it in very few lines. Elimination, just get the essence.” In his remarks opening the exhibit, Mr. McDowell pointed out that fashion illustration reahed its zenith with the fashion magazines of the 1930s and 40s, which were aimmed primarily at upper class ladies. As the demographics of their readership changed in the 1950s, the publishers began to favor photographs over illustration in order to appeal to a younger and broader audience. By the end of the century, photographs had all but replaced illustration in the fashion magazines. The exhibit chronicles this period with examples of works from throughout this period. It includes several works by Kenneth Paul Black, who Mr. McDowell called “the last of the great fashion illustrators.” However, I was most attracted to the works of contemporary British artist Jason Brooks because of the emotion he conveys in a minimum of lines. It was an exhibit rich in fashion history. But the pictures were not just of interest for their historical value. They were good pictures.  “Constable and McTaggart: A Meeting of Two Masterpieces” at the National Gallery of Scotland is a small exhibit that provides insight into the evolution of art. John Constable was one of the great English landscapes. Born in 1776 into a wealthy merchant family, Constable intially struggled for success but by the end of his life, he had become a member of the Royal Academy and had achieved fame in Britain and in Europe. The paintings that established Constable's reputation during his lifetime are polished works that follow in the tradition of the old masters. His inspirations included works by Claude Lorrain and Peter Paul Ruebens. However, distinguishing Constable's works from traditional landscapes was considerable emotion. “Painting is but another work for feeling.” Some of Constable's most successful works were monumental paintings that he called “six footers.” These monumental works have impact not just because of their size but because of the aforementioned emotion that Constable put into his works. His last six-footer “Salisbury Cathedral From the Meadow” (1831) is on display at the exhibit. The cathedral is seen in the distance with dark storm clouds surrounding it. While Constable disdained the traditional practice of altering nature to create an ideal landscape, he has added a rainbow that is not in the preparatory studies for the painting. Hope for the future after the passing storm. In preparation for the paintings he exhibited, Constable would do oil sketches. These paintings are much more impressionistic with bold expressive strokes. They were never meant for sale or public display but rather were meant to be references, memorializing a particular scene or a cloud formation etc., for use in a future more polished work. As a result, the oil sketches were not exhibited until after Constable's death. The exhibit contains several of these oil sketches. William McTaggart was also a landscape painter. He is sometimes called the “Scottish Impressionist.” Born in 1835, McTaggart was a generation or so after Constable. Nonetheless, he was greatly inspired by Constable. Constable's influence on McTaggart can clearly be seen in the exhibit. For example, McTaggart's “The Storm” is a monumental work of the size of Constable's “Salisbury Cathedral.” However, the style of the work is similar to the style of Constable's oil sketches with loose expressive brush strokes and impressionistic vagueness. Like Constable's, McTaggart's works are full of emotion. The exhibit thus shows how an idea developed as a tool by an artist in one generation can be carried forward in a later generation to become the final end product. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed