|

I recently participated in a painting class on Norwegian Breakaway. Entitled Canvas By U, these classes are part of the entertainment programming throughout the Norwegian Cruise Line fleet. These painting classes are a popular activity. Guests must sign up beforehand for a class. This is done via a list in the ship's library. The daily program announces the time when the list will open. On the voyage that I was on, the sign-ups began as soon as the staff member in charge of the library arrived in the morning. Within a few minutes, all of the places are usually filled despite the $35 per class fee.. There are only a dozen or so places for each class. I was told that to have more places would dilute the experience as the instructor would not be able to give enough time to each participant. The number of classes held on each cruise varies. Typically, the classes are held on days when the ship is at sea. Therefore, as a general rule, the more sea days on a given cruise, the greater the number of classes. However, the art classes have to compete with other activities for space and staff so it is not automatic that there will be a class on every sea day. Rather than having professional artists teach the classes, Breakaway uses members of the ship's activities staff who have received training in how to present these classes. While their knowledge of art technique may be limited, they are experienced in working with people and in making activities enjoyable. An effort is made to assign the classes to members of the activities staff who have an interest in art but the instructor for any given class could be any member of the activities staff. The class I attended was held in the Headliners comedy club. Two rows of tables with easels and blank canvases were arranged around the small stage. On the stage was a table with a similar set-up. In addition, there was an easel with a completed painting. Each participant's objective in this class was to make his or her own version of the painting displayed on the stage. The instructor emphasized that while everyone would be painting the same subject, each participant's end-product was to be his or her own painting. Therefore, everyone was encouraged to use their creativity and make whatever variations they wanted. The painting that served as the model in my class was a picture of a tropical island at sunset. It had a colorful red sky, ocean, sand and a grove of palm trees. Different paintings are used as the model for different classes. Thus, a guest could participate in several classes without repeating the same painting. The instructor took the class through the process of painting this picture step-by step. Beginning with the island, she pointed out what color(s) to use, how to mix the paint with water, and which brush to use. She then moved on to painting the sky, the sea, and finally the palm trees. To make these paintings, each participant was equipped with a tray with dollops of a half dozen (tempera) colors, two brushes and a 12 by 16 inch canvas board. In addition, each had a disposable apron and gloves. As the participants painted, the instructor moved about making suggestions and encouraging remarks. There was little conversation between the participants as each was very intent on his or her own painting. From what I could gather, most of the people participating in the class had little or no experience with painting. However, all were interested in painting and were keen to experience what it is like to create a painting. Some displayed a natural talent for painting. All seemed to display a sense of accomplishment as the class drew to a close.  Royal Caribbean's Anthem of the Seas has a sophisticated contemporary décor. In fact, it is often said that the ship's decor looks more like a ship from Royal's premium affiliate Celebrity Cruises than the Las Vegas style décor of some of Royal's earlier ships. Accordingly, the art collection on Anthem is less aimed at eliciting a “wow” and more aimed at contributing to the ship's upmarket atmosphere. Anthem's art collection was assembled in partnership with International Corporate Art. It includes some 3,000 works of art. Almost all are contemporary works. The theme of the collection is “What Makes Life Worth Living.” According to the booklet about the collection, this theme encompasses “people, leisure, fashion, art &literature, food, adventure, entertainment & nature.” This scope is perhaps too broad as it is difficult to discern the theme just by walking around the ship and viewing the various works. However, knowing the theme is not vital to enjoying the art. Several large installations are included in the collection. At the center of ship's public areas is a grand chandelier created by Rafael Lorenzo Hemmer called “Pulse Signal.” It consists of some 200 light bulbs suspended from cords and arranged into a pleasing contemporary shape. The lights blink on and off in various arrangements thus changing the shape of the piece and the atmosphere of the area. It is a visually interesting piece. Guests can control the blinking of the lights by putting their hands on a pad that is located beneath the chandelier. The blinking is then synchronized with the guest's pulse. This does allow for viewer involvement with the art but I find it somewhat gimmicky and unnecessary. Just aft of the chandelier, ascending up the atrium is the prettiest piece in the collection, Ran Hwang's “Healing Garden.” Dark tree branches with bright blossoms are set against a gold background. The work recalls traditional East Asian cherry tree paintings. However, the artist has included non-traditional materials such as crystals, buttons and pins, which give the work a glamorous look. Going further aft, you come to a monumental sculpture by Richard Hudson. It is a swurling mass of highly polished metal. Although entitled “Eve”, it has become widely known as “The Tuba” because of its twisted horn-like shape. Despite this unfortunate nickname, it is an important piece consistent with the upscale shops, the cosmoploitan wine bar and the specialty restaurant that surround the plaza in which it is the centerpiece. You can find works that contribute to Anthem's sophisticated atmosphere throughout the public areas and on the staircases. However, there is also whimsy in the collection. For example, in each of the elevators there is a giant image of an animal. Deming Harriman has manipualted these images so that the various animals are wearing items of human clothing. By adding these items, the artist gives the animals human personalities, making the images both amusing and a commentary on human foilbles. Atop the ship is a larger than life sculpture of a giraffe wearing a swimming costume and an inner tube. Known as “Gigi” this lovable character by Jean Francois Fourtou marks the ship's amusement park area. There is also art along the corridors leading to the passenger cabins. These include contemporary photos staged so as to look like advertisements or scenes from 1950s America. There are also posters with inspirational slogans like the ones that the youth culture used to decorate college dormitories in the 1960s. Overall, the Anthem collection is successful. The theme is perhaps too broad to present a coherent message. However, the pieces are visually pleasing and often thought provoking, Also together, they serve to support the overall atmosphere of the ship. Above: Richard Hudson's Eve provides a centerpiece for one of the ship's plazas.

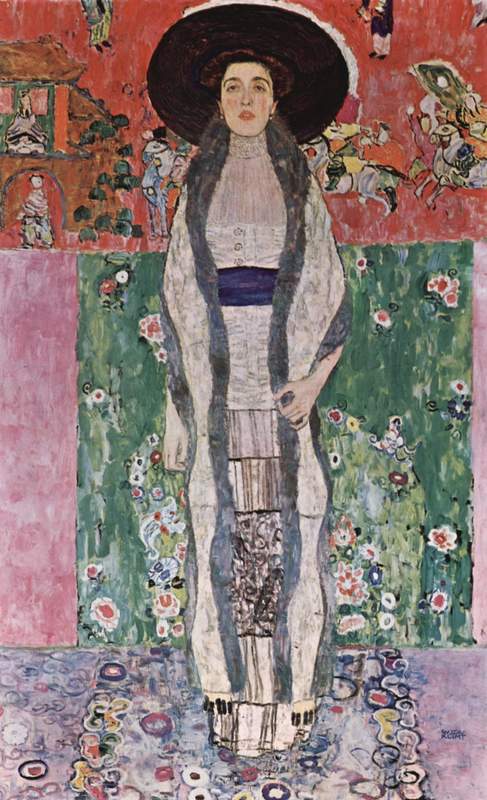

Below left: Ran Hwang's “Healing Garden” in the ship's atrium. Below right: "Pulse Signal" by Rafael Lorenzo Hemmer is in the center of Atrium's public area. The centerpiece of the Neue Galerie is the Klimt Gallery on the second floor. This room is home to ten or so works by Gustav Klimt. While there are many interesting works in the Neue Galerie, this is where you find the most visitors.

Undoubtedly, Klimt is the best known of the Austrian and German artists featured in this museum. But what makes his art successful? Klimt was born in 1862 outside of Vienna. His father was an engraver often working with gold but Gustav grew up in poverty. He received his artistic training at the State School of Arts and Crafts as did his brother Ernst. The teo brothers formed a partnership with fellow artists Franz Matsch and found their first success doing conventional history paintings. Gustav was not satisfied with conventional art. Therefore, after Ernst's death, Gustav became a founding member of the Vienna Secession, a group who sought to break away from the rules of the art establishment of the day. Nonetheless, his unconventional style was appreciated by Vienna's growing middle class who commissioned him to do portraits. On the surface, Klimt's private life might appear to have been conventional. All his life, he lived in an apartment with his mother and two sisters. After Ernst died, he became the guardian for his niece. He never married. But when you look a little deeper, you find that surface appearances can be deceptive. When Gustav died in 1918, the court handling his estate received 14 petitions for child support. The court concluded that three of these were proven. Such claims were consistent with the widespread rumors that Gustav had had numerous affairs with his models as well as with some of the rich ladies whose portraits he had painted. In the studio, he dressed only in a loose robe and there were tales of models cavorting between posing for erotic drawings. Thus, Klimt was both an artistic rebel and a very sensuous individual. These are also the hallmarks of Klimt's best works. The superstar painting of the Klimt Gallery is “Adele Bloch-Bauer I” This painting was the subject of the popular film “The Woman In Gold” but that is not the only reason people stop and linger in front of it. It is not a conventional portrait. Indeed, only the sitter's head, shoulders and hands are easily discernible. The golden gown that covers the rest of her body blends into the background. It is a two dimensional picture full of decorative designs and geometric patterns. Yet, the various elements of the picture come together to support the face, which dominates the sea of gold. The face is not classically beautiful but it is attractive. Her eyes are soulful and her red lips sexual. It was believed at the time that Adele was one of the women with whom Gustav had an affair. His painting “Judith,” which Adele also posed for, certainly suggests that their relationship was more than platonic. Returning to the portrait, this face surrounded by sumptuous gold leaf makes the work very sensuous. Also in the Klimt Gallery is “Adele Bloch-Bauer II,” a slightly later portrait of the same person. It does not have the gold work of the earlier portrait and thus is not as bold. The figure is more conservatively dressed in what was probably a daytime outfit and stands out more than in the predecessor painting. Still, it is an unconventional portrait, Once again it is two dimensional. Colorful rectangles decorated with Japanese-inspired designs make up the background. The figure is not posed provocatively but rather she is straight as a pillar. Nonetheless, her sensuality comes through in her face through Klimt's handling of the eyes and the lips. She is portrayed intriguingly but with a touch of innocence. On the same wall is “The Dancer,” which is similar in dimensions and in composition to “Adele Bloch-Bauer II”. It is perhaps more colorful and more flesh is more exposed but it works for generally the same reasons. Most of the other pictures in the Gallery are landscapes. They recall works done by the Impressionists and the Post Impressionists and would have been unconventional at the time they were painted. However,without the human figure there is little sensuality and therefore less interest.  Matisse in the Studio at the Royal Academy of Arts presents a number of works by Henri Matisse along with various objects that are depicted in those works. Henri Matisse was born into a well-to-do merchant family Northern France in 1869. When he became an adult, he saw himself as following a career in the law. To this end, he studied law and when he obtained his qualifications, he found a position as a court administrator. It was not until after his mother gave him a set of art supplies while he was convalescing from an illness that he found art was his true calling. During his long career, Matisse's style continuously evolved as he incorporated new inspirations into his art. He began with traditional European art but along the way drew inspiration from the Impressionists, Post-impressionists, African art and Islamic art as well as from the contemporary art of the first half of the 20th century. While his works sometimes bordered on abstraction, they always held a connection to recognizable real world objects. Throughout his life, the artist collected furniture, utensils, everyday objects and works of art from several cultures that he found visually appealing. Sometimes these objects would appear in his paintings again and again. He analogized them to actors who appear in multiple plays. This exhibit brings together some of these objects along with the works in which they appear. For example, the exhibit includes two silver chocolate pots that appear in a Matisse still life. There is also an ornate Venetian chair that the artist liked to paint. At the end of the day, most of these objects are just ordinary objects. However, they are of interest for two reasons. First, they are objects that once were the possession of a great artist and thus have historical interest just as the hat that Napoleon wore at Waterloo would be of historical interest. Second, they show that a great artist can draw inspiration from an ordinary object and transform its image into something that is beyond the ordinary. Of greater interest are the works of art from other cultures that Matisse collected. Objects such as African masks and sculptures were not so much subjects of his paintings and sculptures but rather things that influenced his style. The influence of the African masks can clearly be seen in his portrait drawings. He has adopted the simplicity of line of the African artists. But, while the African works conceived for religious purposes - did not seek to depict specific individuals, Matissse captured the character of the individuals portrayed. Thus, one can see the evolution of art. Even leaving aside the juxtaposition of the objects and the works of art, this is still a good exhibit. It presents works from across the span of Matisse's career. As a result, it contains quite a few impressive works of art. With regard to the mechanics of the exhibit, there were too many people for the space. Admission was by timed-ticket, which is supposed to prevent overcrowding. Nonetheless, there were too many people in the exhibit area when we were there. The crowd made it difficult to study and appreciate the works. This was compounded by having groups of school children laying on the floor around some of the works trying to do projects related to the exhibit. You had to be careful not to step on anyone. It would have been much better both for all concerned to have had separate times for the classes and for the general public.  It is not unusual to find an art exhibition on a passenger ship. Most cruise ships have an art gallery that sells prints and original works of art. What is unusual is for a ship to host a preview of an art exhibit that will be seen on land in a major city. As part of its 2017 Transatlantic Fashion week, the ocean liner Queen Mary 2 held a preview of “Drawing On Style: Original Fashion Illustration.” This exhibition was a preview of a larger exhibition held at the Gray MCA Cheryl Hazon Gallery in New York City. The preview presented 21 works by 10 artists. It was held in the annex to QM2's permanent art gallery. Until fairly recently, illustration was a somewhat disparaged stepchild of fine art. In part, this was due to the fact that illustration has commercial connections. It is often used in advertising to sell a product or service. Also, illustration was often used in conjunction with a book or a story to elaborate on an idea or a point made by the author of the book or story. In such situations, it was argued that the illustration is subservient to the book or story and not a stand alone artistic concept. The old view of illustration lost ground as people came to realize that a good illustration can stand on its own without regard to the product or story it was commissioned to serve. Indeed, at this exhibit, it is hard to detect what fashion designer's conept the works were originally intended to illustrate. It s only by reading the signage that you find that a given work was done for one of the great fashion houses or a well-known fashion magazine. In other words, the works stand on their own. The works on display were drawings, often pen and ink with a brushed wash but also some graphite works and some watercolors. They were not traditional drawings. Rather, like the Mask paintings of Henri Matisse, they distill the subject matter to its essential lines. Colin McDowell, fashion commentator and one of the artists whose works were included in the exhibit, explained: “In fashion illustration, you are creating a mood, a feeling and you can do it in very few lines. Elimination, just get the essence.” In his remarks opening the exhibit, Mr. McDowell pointed out that fashion illustration reahed its zenith with the fashion magazines of the 1930s and 40s, which were aimmed primarily at upper class ladies. As the demographics of their readership changed in the 1950s, the publishers began to favor photographs over illustration in order to appeal to a younger and broader audience. By the end of the century, photographs had all but replaced illustration in the fashion magazines. The exhibit chronicles this period with examples of works from throughout this period. It includes several works by Kenneth Paul Black, who Mr. McDowell called “the last of the great fashion illustrators.” However, I was most attracted to the works of contemporary British artist Jason Brooks because of the emotion he conveys in a minimum of lines. It was an exhibit rich in fashion history. But the pictures were not just of interest for their historical value. They were good pictures. “Eighteenth Century Pastel Portraits” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small exhibit of European pastels. It includes, French, Italian, German and British works from the museum's collection.

An exhibition of pastels is not all that common. Works done in pastel are light sensitive. Prolonged exposure to light causes some pigments to fade. In addition, most pastels are done on paper and paper can fade or deteriorate with prolonged exposure to light. As a result, museums generally exhibit pastels in rooms with dim light and even then only for brief periods. The difficulties associated with such arrangements prevent museums from mounting pastel exhibitions very often. Essentially, a pastel is made up of pigment and a binder such as gum. The combination is then molded into a rounded or squared stick. The artist can then use the sticks in the same manner as a pencil. In other words, he or she can create a work without using brushes or mediums such as oils. Historically, pastels were often referred to as crayons. However, pastels differ from modern crayons in that the binder in crayons is usually wax. Pastels are more powdery than modern crayons. While crayons stick to paper better than pastels, pastels are easier to blend and they cover the ground more easily than crayons. Another somewhat confusing term that you often see is “pastel painting.” A pastel painting merely means that the pastels cover the entire ground. A pastel that leaves part of the paper exposed is a “pastel sketch.” It is believed that pastels were invented in the 15th century. There is evidence that Leonardo Da Vinci knew of pastels from a French artist in 1499. In any event, pastel portraits became very popular in Europe during the 18th century. People were attracted by the luminosity of the pastels and the speed and ease with which they could be used. The exhibit presents works by several of the leading pastelists of that era. Rosalba Carriera specalized in pastel portraits and became one of the most successful women artists of all time. She began by painting miniatures but by 1703, she had mastered pastels. Not long after, merchants, nobles and visitors to Venice were queuing for her pastel portraits. She went to Paris and painted the king and his nobles. She went to Vienna and the Holy Roman Emperor became her patron. Carriera is represented by a portrait of a young Irishman dressed in a cloak and tricorne hat. The mask that he has shifted away from his face shows that he is in Venice for the Carnival. Proud and dashing, it is the image of a young noble living life to the full in that romantic city. John Russell was the leading English pastel portraitist. In fact, he was appointed pastel artists to King George III. He also wrote the still inflential book Elements of Painting with Crayons. Russell is represented by three works. One is a charming portrait of his daughter with a baby. The other two are commission portraits of a merchant and his wife. She looks like the dominate one of the couple while he seems to have the look of someone who knows when he is well off. The signs by the paintings tell us that she was an heiress and that when the couple married, he took her family name. Adelaide Labille-Guiard was a member of the French royal academy of painting and sculpture. She is represented by a portrait of Elisabeth de France, the younger sister of King Louis XVI. A virtuous and religious person, there have been calls for pleasant looking person's beatification. However, there is always an element of tragedy in pictures of the members of this doomed family. The images in this exhibit are in sharp contrast to the familiar pastels of artists such as Degas. Rather than strong expressive lines, these works are soft and smooth with no trace of the artists' strokes. Still, they subtlety convey the personalities of the sitters. “Frederic Remington at the Met” is a small, introductory exhibit presenting some 20 paintings, sculptures, works on paper and illustrated books relating to Remington. Although famous for his depictions of the Old West, the artist lived during much of his life in the New York City area. It is known that he came to the Metropolitan Museum (the "Met") to study works. In addition, several of his works came into the Met's collection during Remington's lifetime.

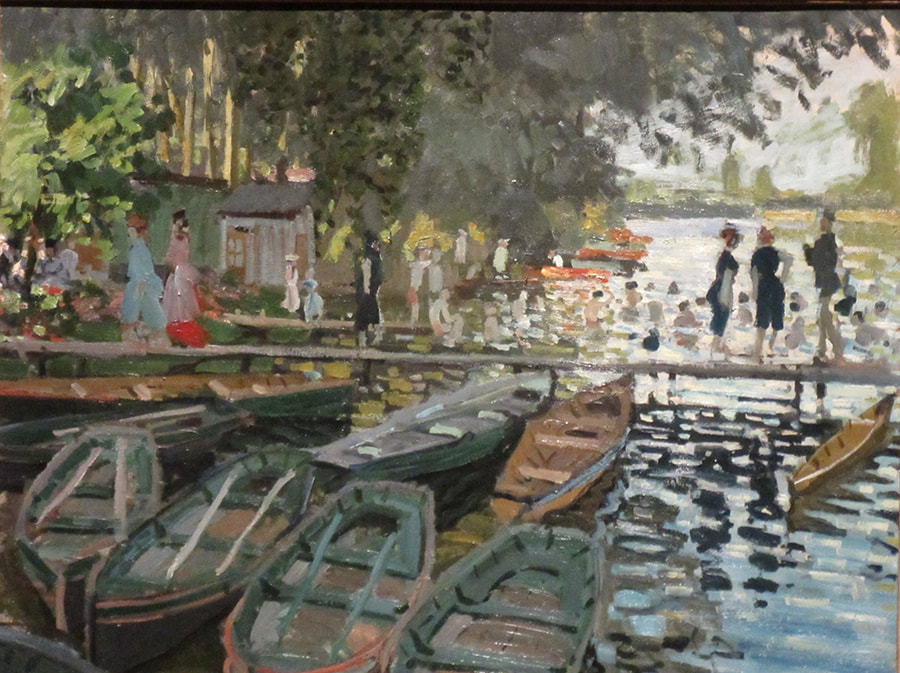

Frederic Remington was born in upstate New York. His father, who was a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War, hoped that his son would follow a career in the military. However, when Frederic entered Yale in 1878, he choose to study art. More interested in playing football than studying, he left Yale after only three semesters. With the idea of investing the inheritance he received after his father's death in a mine or a ranch, Frederic set out for Montana in 1881. Although his investment plans did not pan out, it was an experience that would shape the rest of his life. Remington was captivated by the spirit of the Old West and sketched the cowboys, soldiers and Native Americans that he encountered. He would return to the West again and again throughout his career as a source of inspiration. Remington sold his first sketch to Harpers Weekly in 1882. This was the beginning of a successful career as an illustrator. In addition to numerous magazines, Remington would go on to illustrate books by Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister as well as Remington's own novels. Returning east, he moved to Brooklyn and to build his artistic skills enrolled for three months at the Art Students League of New York. He also studied works on display at the Metropolitan Museum, particularly those of the French academic painters. The exhibit gives a glimpse of Remington's work as an illustrator. There are examples of published works as well as one of his preliminary sketches made on the scene for a work that would be completed in the studio. However, the most interesting of these works are monochrome oil paintings. At first glance, these appear to be black and white photos of paintings. However, you quickly see that they are the original paintings. They were done in black and white to facilitate their reproduction in the magazines of the day. Remington was not satisfied with being an illustrator. At that time, illustration was considered a lesser form of art or, in some circles, not really art at all. In illustration, it was argued, the objective is to support the written words, the concept and inspiration thus coming from the writer rather than the mind of the illustrator. Moreover, illustration was viewed as too commonplace and too commercial. To achieve recognition as a serious artist, Remington began exhibiting paintings in 1887 and had his first solo exhibition in 1893. Although his works were popular, he remained somewhat dissatisfied and later in his life he burnt many of his early works. A highpoint of the exhibit is Remington's painting “On the Southern Plains.” One of Remington's later works, its color and style reflect the artist's movement away from French academic painting toward a more impressionistic style. It shows a group of cavalry soldiers, guns drawn riding to meet some unseen foe. They are not formed in a battle line like cavalry soldiers preparing to attack did in those days. Rather, they ride as a group of individuals - - very American. As throughout Remington's works, the people depicted are noble and engaged in a worthy pursuit. Whether that is a historically accurate portrayal of the Old West is irrelevant. Like a John Ford movie, it has a romantic, heroic appeal and that is good for the soul. In 1895, the sculptor Frederick Ruckstull taught Remington how to do sculpture. Remington went on to create some 22 different bronzes. The exhibit has several of them on display including his first statue, “The Bronco Buster.” Remington's statues are small rather than monumental. There are no busts of famous men. Rather, the statues are of the common people of the Old West. While the artists of the Hudson River School and other artists who depicted the frontier were interested in its wondrous landscapes, Remington was interested in people. And the bronzes depict people in action - - whether it is a cowboy on a bronco, a mountain man going down a steep slope or a Cheyenne warrior speeding along on a horse, there is motion in these statues. Tragically, Remington died at the age of 49 due to complications arsing from an appendectomy In those days, it was the fashion for successful men to overeat. As a result, the once lean athlete was some 300 pounds when he died. Moreover, health problems brought on by his weight prevented him from working outside the studio towards the end of his life - - something he very much desired to do as he became interested in the work of the Impressionists.  Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Joan Mitchell's "Ladybug" Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, a temporary exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, brings together the works of more than 50 artists to illustrate the contribution of women artists to modern art. The works come from the Museum's collection. Following World War II, the art establishment became dominated by abstract art. Although the artistic community at the time regarded itself as avant garde and progressive, it was not very tolerant of competing ideas. For example, the doors of the galleries were closed to artists working in more traditional or realist styles. So too, the galleries - - and too often the minds of the art world - - were largely closed to women artists even those doing abstract work. In the post war period, there were few, if any, mutual support groups for women artists. Watching my mother's struggle (see Art of Valda), what help she received seemed mostly to come from male artists who she had met while at the Art Students League of New York. Thus, for a woman artists to become recognized during this period was very much an act of individual achievement. This exhibit brings together the works of a number of woman artists who managed to overcome the prejudice of the time. It documents that women indeed contributed to the various schools of abstraction that dominated this period. Although the exhibit presents these works as works of women artists, it is important to note that these artists did not identify themselves as women artists and were not just competing against other women. The goal was to be artists who produced art that would compete in the marketplace of ideas with all other art regardless of the sex of the person who produced it. Perhaps the best known school of abstraction at the time was Abstract Expressionism. The enormous drip paintings of Jackson Pollock are hallmarks of this school. It was widely believed that such monumental works required masculine strength and gestures. However, the exhibit documents that women artists were producing similar works on a large scale. These artists included Lee Krasner, the wife of Jackson Pollock, who is represented in this exhibit by her work “Graea.” The curves of paint in this work have an almost floral, organic look. Abstract expressionism is about emotions and the work I found that evoked more reaction in me was Joan Mitchell's “Ladybug.” I found the color combinations visually pleasing and the lines moving and exciting. I also was impressed by Helen Frankenholer's “Trojan Gates.” Although a large canvas, it seemed more cohesive and unique in its approach than many abstract expressionist pieces. At the opposite end of the spectrum is “Reductive Abstraction.” Here, the idea was to remove the human touch from the work. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was much talk about human isolation and the potential that the mindless application of science would create a sterile environment in the future. Accordingly, some artists created futuristic works based upon mathematical or scientific concepts that were devoid of the human touch. Jo Baer's “Primary Light Group: Red, Green and Blue” is made up of three canvases, each of which is primarily a blank white square. Around the outer edge of each of the squares is a narrow black border. The three canvases differ only in that on one there is the color of the narrow space between the white area and the border. On one it is red; one, it in green; and one it is blue. The concept relies on the work of physicist Ernst Mach on the optical effects of placing colors next to black. I found the work too devoid of emotion. In addition, it reminded me of the demonstrations in high school science class when the teacher would illustrate some principle by using a clever but meaningless gimmick. The exhibit also shows that women artists made contributions in bringing abstraction to textiles. Vera Neuman's “Stone on Stone” made in the 1950s appears to be a forerunner of the designs used in the fashion revolution of the 1960s. A more disquieting work is Magdalena Abakanowicz's “Yellow Abakan,” a large, rumpled piece of fiber that hangs on the wall like the corpses in a butcher's freezer. It is not pretty but it evokes emotion. Finally, the exhibit concludes with Eccentric Abstraction.” These are works where the artist used materials not traditionally used in making art. The challenge in such works is to add enough creativity to the project so that it becomes a work of art rather than a pile of junk. Lee Bonteciu's “Untitled” employs pieces of used canvas conveyor belts to form a swirling, three dimensional object. Its industrial coloring gives it a dark, foreboding feel. Once again, it is not pleasant looking but it is evocative of emotion. This week, I wanted to talk about Claude Moent's “Bathers at La Grenouillere.” which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London.

Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840. His father was a small businessman and the family moved to Le Harve about five years later so that his father could join a wholesale grocery firm that was owned by family members. Thus, Monet came from a middle class background. From an early age, Claude displayed a talent for drawing. Over time, he developed a reputation in Le Harve for his comic drawings and caricatures and was able to derive income from the sale of such works. With such a beginning, one might well expect that Monet would have developed into a portrait painter. However, one day when he went out to watch Eugene Boudin work on a landscape, he realized that landscapes were what he wanted to paint. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.” Friends and family recognized that Monet had talent. However, they were unanimous in saying that he needed to refine that talent by studying in the studio of an established artist. At that time, the most respected artists produced highly polished works with extensive modeling and glazing. The apex of the art world was history painting in which figures were depicted in scenes that told a story. Every artist's ambition was to have a work shown at the prestigious Salon in Paris. Monet was quite independent and bridled against such suggestions. Nonetheless, he went to Paris to study first at the Academie Suisse and later at the studio of Charles Gleyre, an established conventional artist. He did not like the conventional approach to the study of art. Although he often completed works in the studio, Monet preferred to work outdoors, painting directly from nature. However, his time in Gleyre's studio was not wasted because there he met Frederic Bazille and Pierre Auguste Renoir, who would be his compatriots in the Impressionist movement. Despite his dislike of conventional painting, Monet prepared and submitted several works to the Salon during this period. Most were genre paintings depicting contemporary people outdoors. In some respects, these works were reminiscent of Edourard Manet's work, Manet being something of a hero to Monet and his friends. They were more polished and the colors more subdued than Monet's later works. Nonetheless, the Salon rejected Monet's submissions. In the eyes of the juries, the works were unfinished and they failed to tell a story. During these years, Monet was able to sell some paintings but he often spent more than he earned.. Subsidies, first from his aunt and later by Bazille enabled him to continue on as an artist. In 1869, Monet moved with his mistress and young son to a cottage in Saint-Michel near Paris. Renoir was living with his parents nearby and so the two painters would often go out and paint the same subjects together. One of the places they were was La Grenouillere (the Frog Pond) a floating restaurant on the Seine at Bougival. The cafe was attached to a small island and to the riverbank by pontoons. There was a place to moor boats and a place for swimming. It was a very popular venue for socializing and summer fun. Indeed, it achieved such a reputation that Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugene came to have a look. Bathers at La Grenouiller is one of a series of studies Monet made in preparation for a larger more polished work that Monet submitted to the Salon. The larger work was rejected and later lost during World War II. What makes Bathers particularly interesting is that it is a forerunner of the style Monet would use in his later works when he was no longer working with the idea of submitting paintings to the Salon. The artist used color rather than lines to create the image. Figures, water, foliage are all described with a few bold brush strokes. The composition has a snapshot quality - - a scene of everyday life. Monet does not comment on the scene. He does not condemn it as people having frivolous fun nor does he praise it as welcome relief for the everyday worker. He just presents the scene and the viewer can make up his or her own mind. The picture can be dived into four quadrants with the pier dividing the picture horizontally and a vertical line right of center descending from the trees past the boats. Each section is a separate picture. However, the S curve of the river brings the composition together. A painting such as the Bathers would not have been possible only a few years before. The invention of the paint tube in the 1840s enabled Monet to easily transport his palette to the scene. Similarly, the invention of the metal ferrule made flat brushes possible. Such brushes enable Monet to work quickly and their use is documented by the flat brush strokes in this painting. The lesson here being that artists should not be afraid of employing new technology. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed