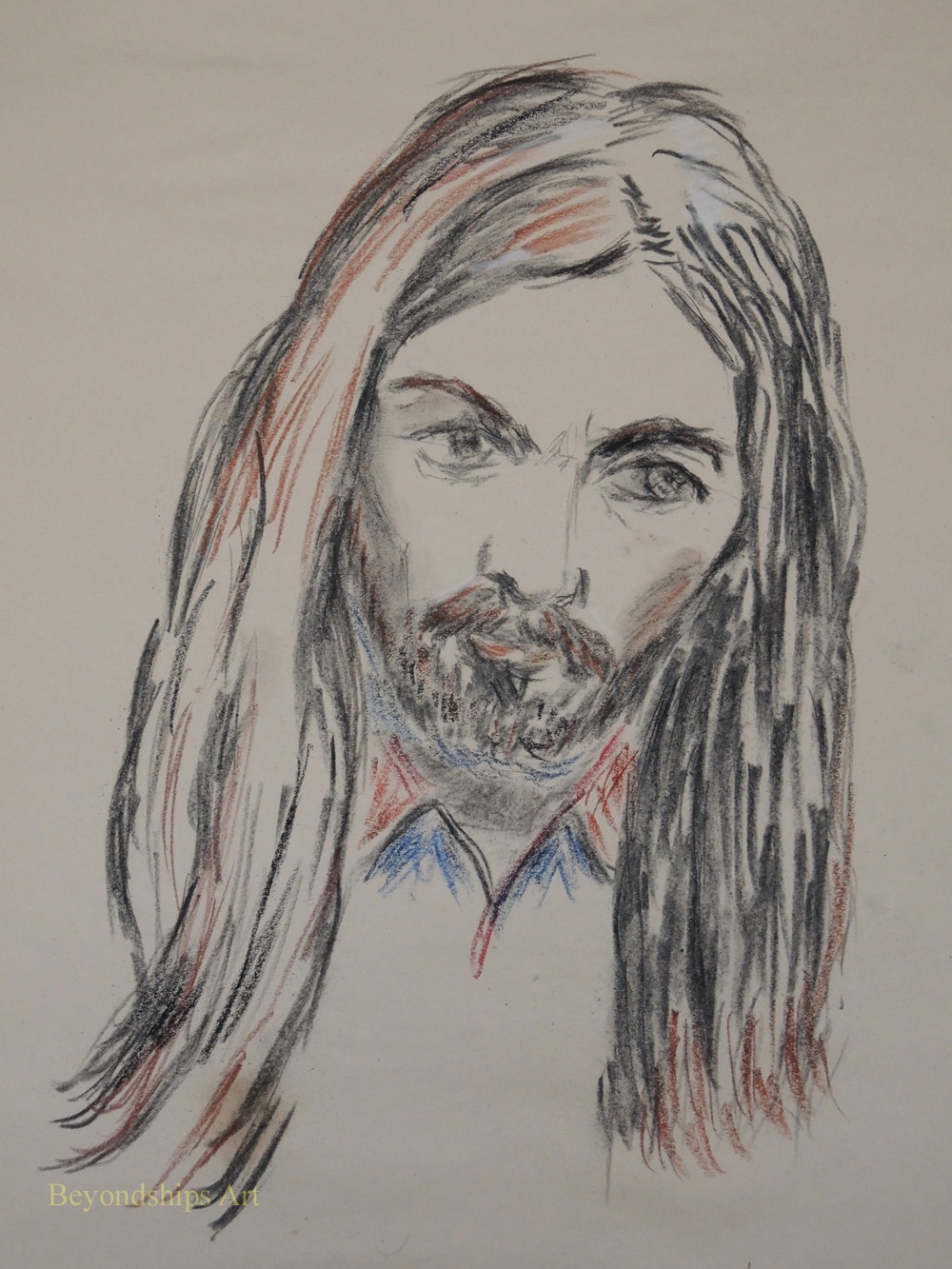

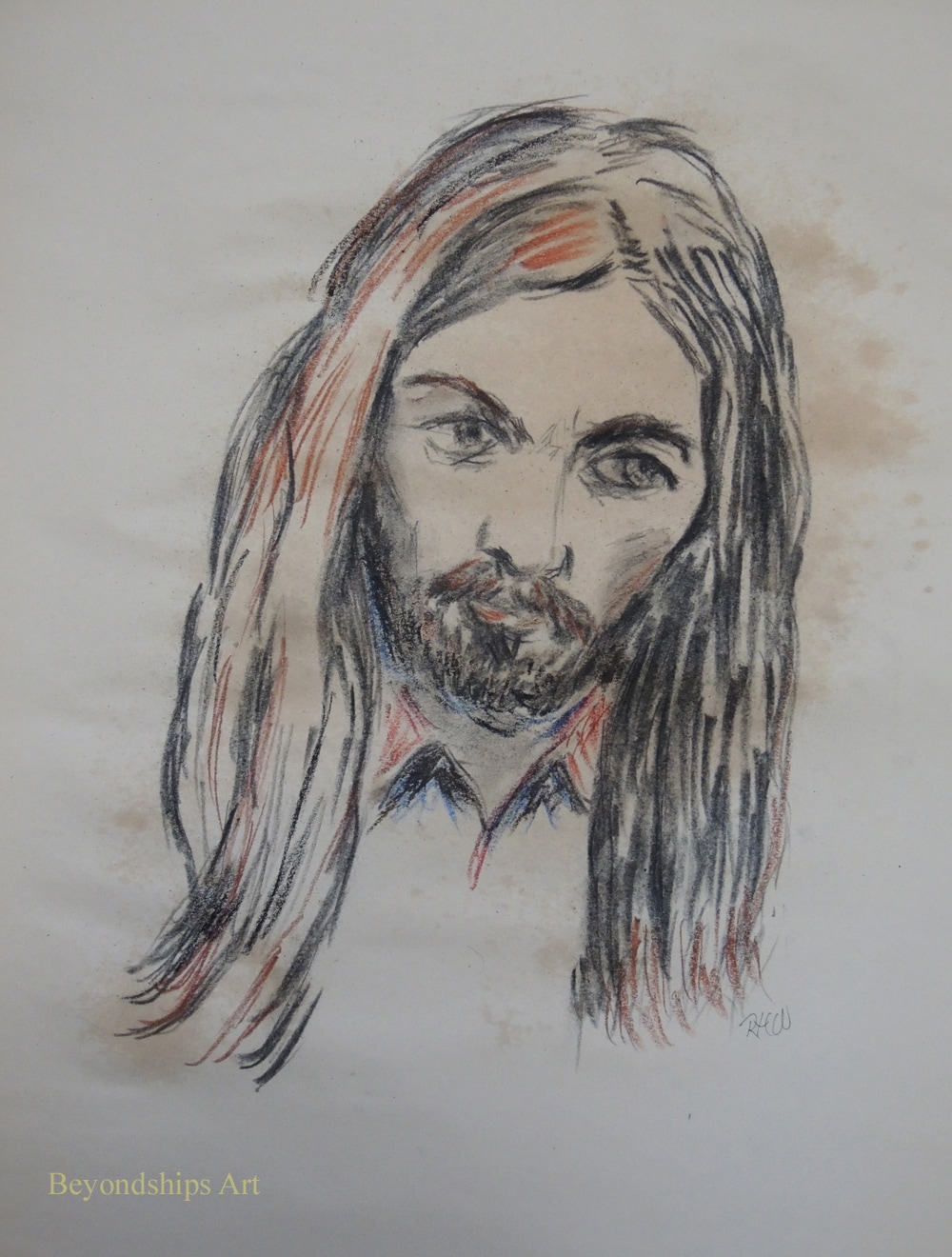

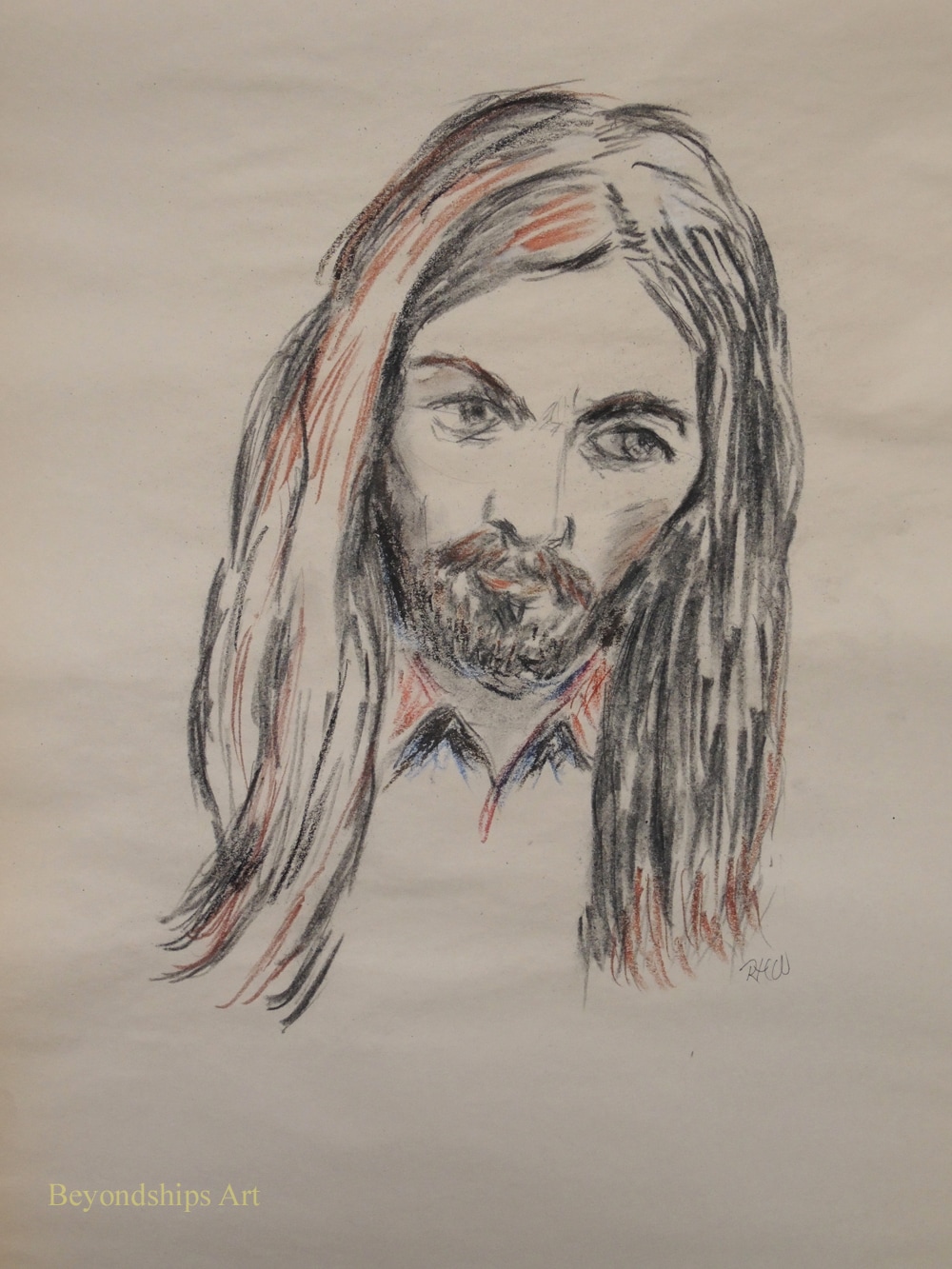

“Forgotten Faces” is an exhibit of some 11 portraits at the National Gallery of Ireland by Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Flemish artists done in the 16th and 17th centuries. What binds all of these portraits together is that the identity of the sitters have been lost over time. The signage at the exhibit asserts that the siters had their portraits painted in order to “mark significant events in their lives, to flaunt their wealth, or to reveal their social standing. All wanted to register their existance in a medium that would outlive them.” However, because the names and life stories of the siters have been lost over time, the exhibit asks “what is the significance of such nameless portraits?” It answers that question: “Perhaps their value lies in the fact that they serve as reminders of the brevity of life, and lead us to remember how we want to be remembered, if at all.” Elsewhere, the museum writes: “Ultimately, however, this display of forgotten faces encourages us to consider people's thoughts about time, memory, identity and legacy, and how portraiture provides us with the illusion of permanence in a changing world.” I found myself in fundamental disagreement with the thesis of the exhibition. The significance of a portrait does not come from the identity of the sitter. The world's best known painting, the Mona Lisa, is a portrait and while people may be curious as to who the woman with the mysterious smile is, who she is is irrelevant. Similarly, Van Gogh's portrait of the postmaster of a small French town is not an important painting because of its subject's identity. A successful portrait is one that says something about the person depicted such as their emotions and their personality. It is self-contained. All that we need to know about the subject is contained in the portrait. The sitter's name, life story and other extrinsic facts are irrelevant. A portrait also conveys something about the artist. The image is not a mechanical recreation of how the sitter looked. Rather, it is the person as seen through the artist's eye. It is an image as interpreted through the artist's intellect, emotions and perceptions. Therefore, if the subjects of these paintings were seeking a form of immortality by having their portraits painting, they achieved it. Some 500 years after their time, people are looking at their images and seeing something of their personality. The museum at times appears to realize this point. For example, in “Portrait of a Spanish Noble Woman” by an unknown artist, the signage says: “this is a highly controlled image that reveals what she and the artist wanted to disclose about her place in society.” Thus, the work not only tells us something about the sitter but also about her times. Similarly, in “Portrait of a Man Aged 28”, also by an unknown artist, the signage says: “His youthful hopeful face lends the portrait poignancy.” Thus, it is conceded that this portrait does convey something about the person depected. While the historical facts of that person's life have disappeared, we nonetheless know something about him through the image that the artist created. The sign, however, goes on: “His anomynity is a reminder that our lives exist in the memories of people we know, and these memories can disappear within a generation or two.” But such a conclusion about the fleeting nature of existence does not really follow from the fact that we do not know the name of the person shown in a particular portrait. Even in a well-documented life, we do not know a person to the same degree as his or her friends knew that person. Thus, famous or anoymous, it can be said that our lives only exist in the memories of the people we know. Once again, the degree to which we know extrinsic facts about a person depicted in a portrait is irrelevant to whether that painting speaks to us. Everything that we need to know about that person is contained within the four corners of the portrait. Of course, some artists are better able to capture and communicate something about their subjects than are others. Thus, we find out more about the people depicted in some works than we do from others. The exhibit contains works by some well-known artists such as Veronese and Tintoretto but the works of the unknown artists are often just as moving. Although a small exhibit of second tier works, “Forgotten Faces” is successful because of the thought-provoking discussion of portraiture.  A smart phone image of a work in progress. A smart phone image of a work in progress. I find that the more I work on a picture, the less I am able to see it. No, I don't mean that my eyes become blurry. Rather, I mean that I am less able to see the picture objectively. This can lead to three problems. First, I can't see the mistakes that I have made. The eyes in a portrait can be positioned at different levels making the subject the look like something from a horror movie. Yet, what I see is something that Leonardo Da Vinci would envy. Second, I go on working even though the picture is finished. A picture can easily be ruined by overworking it. Third, I go on working on a picture even though it will never be anything worthwhile. Some pictures are just failures. There is a tendency to think, if I just make a few more changes it will be a masterpiece. However, in reality, you're just wasting your time. Better to start something new. The inability to see a work objectively occurs because the mind has a tendency to see what it wants to see. Therefore, what is needed is a fresh view of the picture. My mother, the artist Valda, used to recommend holding the picture up to a mirror. This breaks the spell and in the mirror image,you can see the work much more objectively. A technique more suited to the digital age that I often use is to take a photo of the picture with the camera in my smart phone. The objective is not to get an image that you would want to share with friends and family but rather to look at your picture in a different way. My smart phone is well-suited to this task. It takes a serviceable image in almost any light. In addition, I can see the image immediately on the phone's display screen. I often end up taking several pictures as I work. Having used the smart hone to detect a problem, I endeavor to correct the problem on the original picture. Another photo tells me whether I really have solved the problem and whether there are other problems that need correcting. The only problem that I have found with this technique is that it can use up the storage on the smart phone. Therefore, it is best to delete the images as you go along.  Rembrandt, Self Portrait (Image public domain Wikimedia Common) Rembrandt, Self Portrait (Image public domain Wikimedia Common) Portraiture isn't just about capturing a likeness. A good portrait communicates something about the person who is the subject matter of the work. I have always liked the work of the English portrait artist Sir Thomas Lawrence. Many of his subjects were famous people such as the Duke of Wellington but that is not what makes the works interesting. A look in the eyes, the smile, the position of the body reveal something about Lawrence's people even the ones who history has forgotten. You feel like you would have liked to have met them. Along the same lines, this is why most portraits done by sidewalk artists are disappointing. Many are great technically. However, in most cases, the artist is merely producing a likeness without seeking to know or understand the person who is the subject. Since portraiture can (and should) be a way of communicating something about the person who is the subject of the work, it can be a means of self-analysis. In order to say something about a subject, you need to understand how you feel about that subject. The classic example of self-analysis through portraiture is the self-portrait. A good self-portrait reveals how the artist sees himself or herself. Rembrandt did self-portraits throughout his life. As a result, we can see him proud and self-confident at the height of his success as well as melancholy and thoughtful after fortune had turned against him. Towards the end of her life, my mother, the artist Valda, embarked on a series of works chronicling the important moments in her life. Inherent in this project was coming to an understanding about which moments were significant to her. Unfortunately, Valda was only able to produce a few works in this series before she became too ill to work. Inspired by Valda's project, I began my own slightly different project a few years ago. The idea was to do a series of pictures of people with whom I had had significant relationships. I wanted to understand what made those relationships significant, what had happened in those relationships and my feelings toward the people involved. The first step in the project was deciding which relationships were significant. I had in my mind a general idea of the importance of my various relationships but as I began to do the pictures, I realized that some were not really as important as I had thought. Eventually, I came down to four who were game-changers in the sense that I was never the same afterward. I have probably done more than a hundred pictures on this project. For some, I based the image on photographs but most were done from memory. They have ranged from paintings to quick sketches on pieces of scrap paper. In doing the pictures, I have thought about what happened and why. But more importantly, I examined my feelings both then and now. Overall, it has been a worthwhile project. I have a much better understanding of how I got where I am in life. At the same time, I have come to realize that this is an ongoing project perhaps without end because my feelings towards the past change. It has also produced some successful artwork. I participated in an exhibition over the winter in which I showed one of the works from this series. A stranger attending the exhibition spent quite a long time in front of that picture. He then came up to me and said that he liked the picture. “I would like to have met her. You must have really loved her.” While the picture has its technical faults, it must be a good portrait as it successfully conveyed the feelings of the artist. I had an idea for a drawing so I grabbed an old piece of soft charcoal and a pad of newsprint paper and began to sketch out my idea. The sketch was coming along when I decide to use my finger to smudge one of the lines. To my horror, not only did the line smudged, it all but disappeared. Clearly, this image would not stand up to being stored or displayed. By this point, the drawing had progressed quite far along. I thought about copying it over onto a better piece of paper using another medium. But that would be a lot of work and besides I liked the effect that this soft charcoal was producing. So I decided to finish the picture and see if I could find some way of fixing the image to the paper. I use charcoal quite often but I usually do not apply fixatives. I don't like chemical odors and so rather than use chemical fixatives I just store my charcoal drawings as carefully as I can and just accept that there will be some deterioration in the image. In any case, I did not have any commercially available chemical fixatives in the house. When I was in grade school, I remember an art teacher using hairspray to fix a pastel. Do they still make hairspray - - I haven't seen a can for centuries. Also, that smelled awful when the art teacher used it back in ancient times. Somewhere along the line, I had read that Vincent Van Gogh and some of the Impressionists used skimmed milk as a fixative for their drawings. There was some skimmed milk in my refrigerator and so at the risk of having to eat dry corn flakes the next morning, I decided to experiment. There was no other downside because this drawing was not going to survive without being fixed. The article that I read about Van Gogh did not say how he applied the milk to his drawings. Taking a glass and dumping it on the drawing would obviously destroy the drawing as well as create a sloppy mess. Similarly, putting some milk on a paper towel and wiping or blotting it onto the drawing would damage such a delicate image. Spraying it on seemed to be the method most likely to succeed. All sorts of cleaning products come in spray bottles these days. But when I looked through the cupboard, all of the ones that I had seemed to be nearly full and it would be too wasteful to pour out their contents for the sake of a somewhat dubious experiment. Finally, I found a small sample size spray bottle that I had been given on by the spa on a cruise ship. It was almost empty so I cleaned it out. I also had no idea what formula Van Gogh used. Did he mix the milk with something else? Was it diluted? Inasmuch as I only remembered the article saying that he used milk, I just filled the spray bottle with milk straight from the milk bottle. Since I did not know how much milk to apply, I started with a few sprays. This had an immediate effect. A little bit of charcoal came off when I touched the drawing but the lines did not disappear as they had before the milk was applied. I sprayed it a few more times and next to nothing came off when I touched the drawing. The spray had a noticeable effect on the paper. Newsprint is not the best quality paper and apparently it does not like getting moist. There was some discoloration where the spray had been applied most heavily. However, the discoloration had disappeared by the next morning. There was also some slight puckering but I imagine that would not occur with better quality paper. I find it difficult to look at my works without finding something I want to change and so I was interested in whether I could modify the drawing after the milk had been applied. Not surprisingly, I could not intentionally smudge the charcoal to create shadows. However, I found that I could still make modest use of an eraser. Also, there was no problem adding additional lines not only with charcoal but also with Conte and Cray-pas. Overall, I viewed this as a successful experiment. The picture was preserved and it was an easy process with no odor or clean-up required. Portrait of George. Left: The drawing before applying the milk fixative. Middle: The drawing just after the milk had been applied. Right: The drawing the day after the milk was applied.

|

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed