|

Click here for our review of the art exhibition "It's Alive: Frankenstein at 200" at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City.

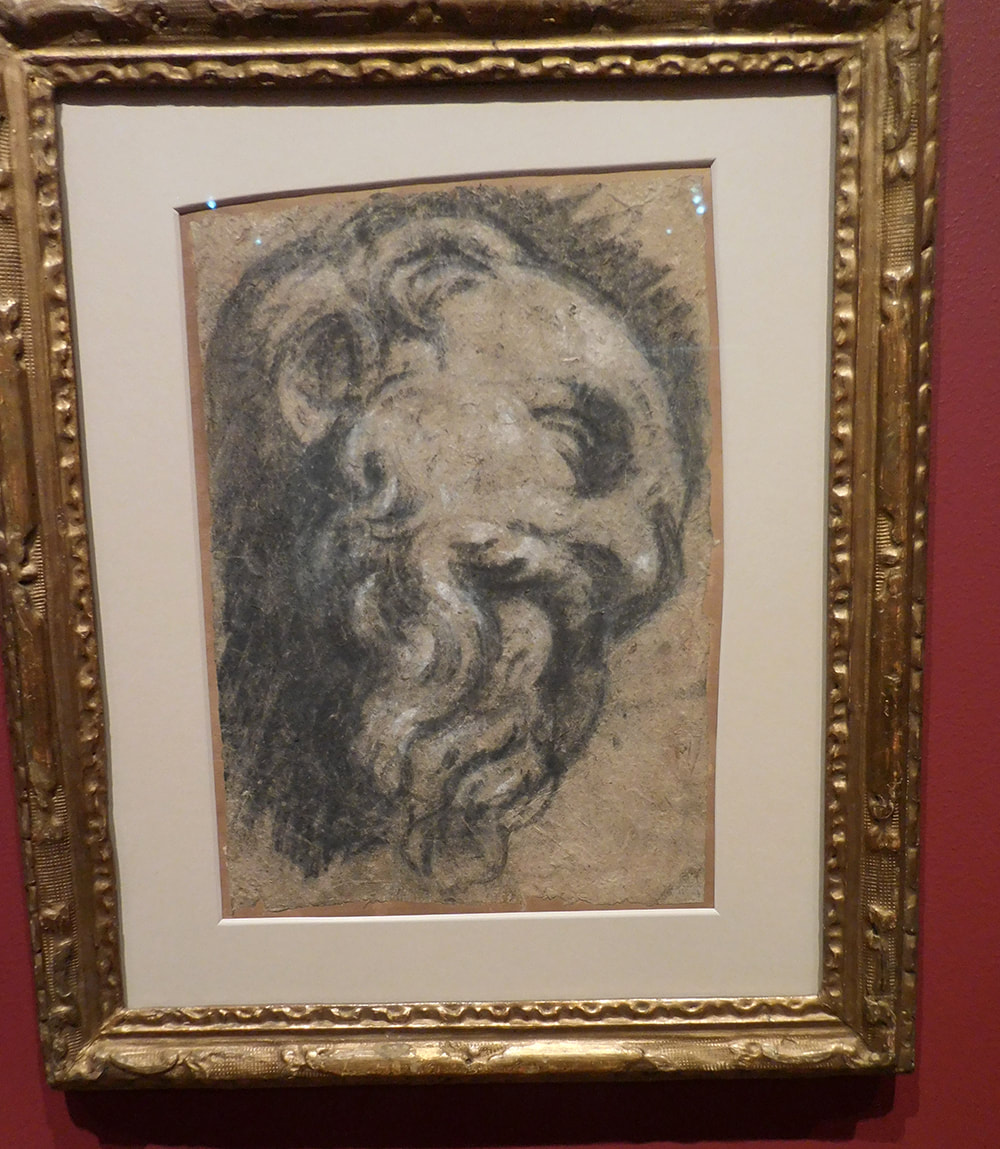

Click here for our review of the art exhibition "Drawing in Tintoretto's Venice" at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City.

Click here for our review of "Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters" at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City

“Drawn In Colour: Degas From the Burrell” recat London's National Gallery brought together 20 works by Edgar Degas from Glasgow's Burrell Collection Gallery along with a number of works from the National Gallery's own collection. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born in Paris in 1834. His father was a French banker and his mother was from a New Orleans Creole family. His father was interested in the arts and encouraged Edgar's interest, often accompanying him to museums in Paris. Indeed, after Edgar made an unsuccessful attempt to fulfill his father's desire that he pursue a career in law, his father provided him with an art studio. Edgar's training in art was quite conventional. He studied at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts including drawing with Louis Lamothe, a disciple of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who Edgar greatly admired. He also traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. In both France and Italy, much of his time was spent copying masterpiece paintings and drawings. With this background, it is not surprising that Edgar's early work was influenced by conventional thinking about art. In those days, history painting was considered the highest form of fine art and so Edgar did history paintings. He also submitted and had works accepted by the Salon, the apex of the art establishment. Soon, however, Edgar's work became quite unconventional. Several factors contributed to this change. In 1864, he met Edouard Manet while he was copying a painting at the Louvre. They became good friends and Edgar came to share Manet's interest in depicting modern life. Following, the death of his father in 1873, Edgar sold off most of his assets in order to pay debts that had been amassed by his brother. As a result, Edgar, who was now spelling his last name “Degas”, had to rely on the sale of his art work to make his living. The primary factor in the evolution of Degas' work, however, was his quick mind. While he always retained his admiration for the great painters of the past, Degas was continually innovating. Diverse inspirations such as Japanese art and the new technology of photography influenced his compositions. He was interested in experimenting with different mediums, branching into photography, sculpture and, most particularly, pastels, which he applied in complex layers and textures. Although often conservative in his thinking on other matters, his thinking on art became quite radical. In 1874, he joined together with several other artists who were taking unconventional approaches to art for an exhibition. The group came to be known as the “Impressionists,” a label Degas hated. Degas helped organize the Impressionist exhibitions and exhibited in all but one of the Impressionist exhibitions. Degas added another dimension to Impressionism. Whereas his colleagues Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro mostly painted landscapes, Degas was interested primarily in the human figure. Whereas the other Impressionists preferred to work outdoors capturing what they were observing at the moment, Degas preferred to work in his studio, sometimes working from photographs or from memory. What connects Degas to the others, however, is an interest in depicting modern life, an interest in light and an interest in using color in unconventional ways. Because there were profound differences in the individual Impressionist's artistic philosophies and because the group included some difficult personalities (including Degas) the group eventually separated. There were only eight Impressionist exhibitions and after 1886, the artists went their separate ways. Degas, who was having problems with his eye-sight, became particularly solitary. Increasingly, he turned to pastels and sculpture. Again and again, he returned to certain subjects such as dancers, horse racing and women bathing. He died in 1917. Sir William Burrell (1861 - 1958) amassed 20 major works by Degas including works from every period of the artist's life. He donated these along with some 9,000 other works of art to the City of Glasgow in 1944. The closing of the Burrell Collection Gallery in Glasgow for renovation provided an opportunity for the Degas to be exhibited in London. The exhibition was presented in three sections: Modern Life; Dancers and Private Worlds - - in short three of Degas' signature subject matters. Although there were a few oil paintings and drawings, most of the works in the exhibition were pastels, Degas' favorite medium The presentation of these works together served to underscore how much of an innovator Degas was. His use of this medium was much different than conventional pastels. The strokes are vigorous conveying energy. The shapes verge on the abstract at times. The colors are often strong and bold. “Charles II: Art & Power” at the Queen's Gallery (London) looks at the role of art in the reign of King Charles II (1660 to 1685).

Charles II's reign was shaped by the English Civil War. Charles's father, King Charles I, sought to be an absolute monarch. However, he came to the throne as the power of Parliament and democracy was growing in England. Eventually, this led to civil war. Charles I lost and was beheaded in London in 1649. Parliament declared the monarchy abolished and established England as a Commonwealth with Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the parliamentary army, as Lord Protector. Both to raise money and to do away with the trappings of monarchy, the royal regalia, furnishings and art collection were sold or melted down. The Commonwealth quickly fell apart following Cromwell's death. Unable to find a leader to replace Cromwell, Parliament reinstated the monarchy and invited Charles II to return from exile. Although he was welcomed back to England with great fanfare and popular sentiment, Charles realized that his position was precarious. He had seen the consequences of his father's absolutist attitude. In addition, while he was in exile, he had had to journey from country to country as various rulers' attitudes shifted from being Charles' allies to wanting to curry favor with Cromwell. As a result, Charles realized that he needed to create a public image that would help secure his position as king. One of the tools that Charles used to build this public image was art. Upon his return, Charles had an elaborate coronation. Since the royal regalia had been destroyed by the Commonwealth, he commissioned new regalia. The sumptuous pageantry connected him to the monarchs of the past and helped legitimize his reign. In addition, the Commonwealth had been heavily influenced by Puritan thinking and the people appreciated the colorful and lively ceremony. Charles and his court also commissioned works of art. Portraits showing the king, his family and his various mistresses in silks and elaborate finery hung in the various royal palaces. These were not done just for vanity but also to show that Charles and his court belonged in these palaces. At this time, collecting prints was becoming popular in England. It was the social media of the day. People purchased prints of Charles and displayed them in their homes. They were also entertained by tales of the various intrigues that were going on at court and enjoyed seeing prints of the portraits of the participants. Charles was also eager to re-build the royal art collection. His father had been a renowned collector. But beyond family sentiment, Charles wanted a first rate collection because such a collection would place him along side the established monarchs of the day. Therefore, a law was enacted calling for the return of works that had been sold by the Commonwealth. In addition, Charles purchased old master paintings and drawings. His collection grew further as a result of gifts from from other nations and courtiers seeking to ingratiate themselves with the king. Using works from the Royal Collection, this exhibition does not merely display works from the time of Charles II but presents them so that their use as a tool of the king is clear. The signage and the audio guide (included in the price of admission) also help to support the presentation of the thesis of the exhibition. Unlike his father who had had the services of Sir Anthony Van Dyck, Charles did not have an artist of genius to do his portraits. Sir Peter Lely and his contemporaries were good draftsmen but their portraits are chiefly of interest because of the people depicted rather than as independent works of art. The difference between the work of good artists and artists of genius is brought home by the examples of old master paintings and drawings collected by Charles II. These works, including works by Titian and Holbein, have an indefinable quality that the Restoration works do not.  “Birds of a Feather: Joseph Cornell's Homage to Juan Gris” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small exhibition that brings together a dozen of Cornell's shadow boxes along with the painting by Juan Gris that inspired Cornell. Joseph Cornell was born in 1903 outside of New York City. He was the eldest of four children. When his father died in 1916, the family was left in bad financial circumstances and had to move into the city. Joseph dedicated most of his life to supporting the family including a younger brother who had cerebal palsy. Painfully shy, Cornell never married and had few relationships and friendships. Cornell had little formal education. However, he was well-read and interested in cultural activities. Accordingly, he spent much of his free time exploring museums and art galleries. As a result, he began to develop his own art. The primary medium used by Cornell was the shadow box. He would take various objects that he discovered on his trips around New York and assemble them together. These juxtapositions of found objects had a surrealistic flavor and he was embraced by the Surrealists and New York's artistic community. On one of his visits to an art gallery, he saw a painting by Juan Gris that he found striking. Gris was born in Spain in 1887 but moved to Paris in 1906 where he became part of the avant garde scene. Although not the inventor of Cubism, he brought that style forward and developed it. The work that inspired Cornell was “The Man at the Cafe.” In it, Gris depicted the criminal mastermind in a popular series of novels. This shady character is almost entirely obscured by the newspaper he is reading. The shadow from his fedora blocks out his face. Wood grained paneling mixes the background and the figure. Done in the Cubist style, it is divided into geometric planes. Cornell made 18 shadowboxes, two collages and a sand tray in the series inspired by Gris' painting. Like Gris' painting, he incorporated printed pages and trompe l'oeil wood grain in these works. There is also a central figure but instead of a criminal mastermind, the figure is a cockatoo. The shadow boxes are much smaller than Gris' painting. Consequently, they are much more intimate visually. Thus, while they may be rooted in the painting, they are a much different visual experience.  “Leon Golub Raw Nerve” at the Met Breuer in New York City is a selective survey of the work of the 20th century American artist Leon Golub. Born in Chicago in 1922, Golub studied art history at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1942. After the Second World War, he studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. There he met his wife, the artist Nancy Spero, to whom he was married for nearly 50 years. The two arists lived in Europe for periods during the 1950s and 1960s. While there, Golub developed his interest in 19th century historical painting and artists such as Jacques Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. He was also interested in ancient Greek and Roman art. As a result, at a time when the art establishment was only interested in abstraction, Golub was creating art in which recognizable human figures were central. Golub, however, was not a conventional artist. While the influences of ancient and traditional art can be seen in his works, he also incorporated much of the force of the abstract expressionist painters. His images were often done with free broad strokes. He added layers of paint and then scraped them away. He left sections of the canvas in its raw state. This technique did not make for pretty pictures but it did make them emotionally powerful. When Golub and Spero returned to the United States in the 1960s, opposition to the Vietnam War was growing as that conflict escalated. Golub became involved in the anti-war movement and violence and cruelty became themes in his art. Other social and political issues such as racial inequality, torture, oppression and political corruption would also draw Golub's attention throughout the rest of his career. An artist seeking to convey a political or social message with a work of art has to be careful to avoid making the work dependent upon the viewer's knowledge of the underlying political or social issue. A scene or a symbol that everyone today would recognize as having a certain meaning may not mean anything to a viewer 20 years from now. Thus, a work that is too heavily dependent upon today's headlines may have no meaning in the future. Golub's works transcend the headlines. For example, “Gigantomachy II' is a monumental painting of a group of muscular male figures fighting, which was done during the Vietnam War. The title refers to a battle between the Olympian gods and a race of giants and the painting recalls an ancient Greek frieze. However, it is not a glorious depiction of battle but rather conveys a sense of cruelty and pain. Thus, it is not just about ending the Vietnam War but is a condemnation of war that continues to have meaning. Along the same lines, in “Two Black Women and a White Man,” Golub presents two black women sitting on a bench with a white man leaning against a wall behind them. Perhaps, it is a group waiting for a bus. However, the positioning of the figures and the way they are avoiding any interaction, underscores the separation and isolation of the races. The scene could be in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement or in South Africa during Apartheid, it could be now. The message of the picture still comes through.  “Provocations: Anslem Kiefer at the Met Breuer” is a large exhibition drawn from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection of works by the contemporary German artist. Anslem Kiefer was born in Germany two months before the end of the Second World War in Europe. Kiefer planned from childhood to be an artist. However, when he entered the University of Freiberg, he began as a pre-law and language student. However, he soon switched to the study of art and went on to studying art at academies in Karlsruhe and Dusseldorf. He studied informally with the artist Joseph Beuys. Now a well-established artist, he lives in the South of France. Keifer's work has been primarily concerned with relating German history and culture to the present day. In particular, he has sought to confront the Nazi era. Following the end of the Second World War, the symbols of the Nazi era were outlawed in Germany. The victorious Allies were concerned that the Nazi movement could be revived if these symbols were allowed to be displayed. For many of the vanquished German people the ban made it easier to forget the horrors that had been committed in their name. However, by the 1960s, German intellectuals were arguing that the Germany had to come to terms with its past. In 1969, Kiefer came to public attention with a series of photographs that he had taken of himself in his father's Wermacht uniform giving the Nazi salute. The photos were taken with a background of historic monuments around Europe and by the seaside. Audiences wondered whether the photos were meant to be ironic or as praise for the Nazis. Kiefer's objective was to cause people to confront rather than bury the past. Kiefer has over the years expanded the scope of his work to include a broad range of German history and culture. However, since the Nazi propaganda machine conscripted much of German music, myth, legend and history, the specter of the Nazi era is never far away. Described as a Neo-expressionist, Kiefer has used a variety of mediums in his work. In addition to traditional painting and photography, his works have incorporated such things as earth, lead, straw and broken glass. He is also known for works on a monumental scale. One such monumental work displayed in the exhibition is “Bohemia Lies by the Sea” (1996). The painting has some of the force of an abstract expressionist work. However, it is actually a scene of a rutted country road extending through a field of poppies. The title is taken from an Austrian poem in which the poet longs for utopia but recognizes that it is unreachable just as landlocked Bohemia can never be by the sea. The connection to the Nazi era is that Bohemia is in the Sudetenland annexed by the Nazis just before the war. Furthermore, poppies are a symbol for lives lost in war. While Kiefer is known for his large works, I found myself drawn more to some of the smaller works in the exhibition. For example, in “Herzeleide” (Suffering heart), Keifer based his watercolor on the image in a Nazi era book of a mother looking at a document informing her that her son has been killed. Nazi propaganda exalted such sacrifices. In his painting, Kiefer has replaced the document with an artist's palette. “My Father Pledged Me A Sword” is based upon Wagner's Ring Cycle operas. In the operas, Woton, king of the gods, thrust a sword into in an ash tree. Later, his son Sigmund is in need of the sword and cries out for it. However, Kiefer has painted the sword not in a tree but in a rock atop a high cliff overlooking a fjord - - much more difficult to retrieve. Even assuming aguendo that the viewer knew nothing about German history or culture, Kiefer's art still works. The works are well composed. Sometimes bleak and sometimes harsh, they are always emotionally powerful and thought-provoking. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed