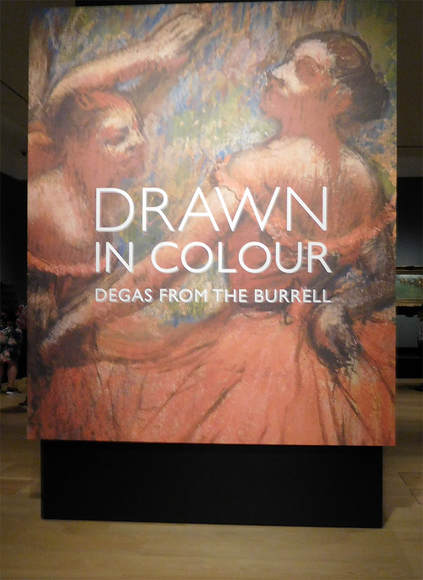

“Drawn In Colour: Degas From the Burrell” recat London's National Gallery brought together 20 works by Edgar Degas from Glasgow's Burrell Collection Gallery along with a number of works from the National Gallery's own collection. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born in Paris in 1834. His father was a French banker and his mother was from a New Orleans Creole family. His father was interested in the arts and encouraged Edgar's interest, often accompanying him to museums in Paris. Indeed, after Edgar made an unsuccessful attempt to fulfill his father's desire that he pursue a career in law, his father provided him with an art studio. Edgar's training in art was quite conventional. He studied at the Ecole de Beaux-Arts including drawing with Louis Lamothe, a disciple of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who Edgar greatly admired. He also traveled to Italy to study the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. In both France and Italy, much of his time was spent copying masterpiece paintings and drawings. With this background, it is not surprising that Edgar's early work was influenced by conventional thinking about art. In those days, history painting was considered the highest form of fine art and so Edgar did history paintings. He also submitted and had works accepted by the Salon, the apex of the art establishment. Soon, however, Edgar's work became quite unconventional. Several factors contributed to this change. In 1864, he met Edouard Manet while he was copying a painting at the Louvre. They became good friends and Edgar came to share Manet's interest in depicting modern life. Following, the death of his father in 1873, Edgar sold off most of his assets in order to pay debts that had been amassed by his brother. As a result, Edgar, who was now spelling his last name “Degas”, had to rely on the sale of his art work to make his living. The primary factor in the evolution of Degas' work, however, was his quick mind. While he always retained his admiration for the great painters of the past, Degas was continually innovating. Diverse inspirations such as Japanese art and the new technology of photography influenced his compositions. He was interested in experimenting with different mediums, branching into photography, sculpture and, most particularly, pastels, which he applied in complex layers and textures. Although often conservative in his thinking on other matters, his thinking on art became quite radical. In 1874, he joined together with several other artists who were taking unconventional approaches to art for an exhibition. The group came to be known as the “Impressionists,” a label Degas hated. Degas helped organize the Impressionist exhibitions and exhibited in all but one of the Impressionist exhibitions. Degas added another dimension to Impressionism. Whereas his colleagues Claude Monet and Camille Pissaro mostly painted landscapes, Degas was interested primarily in the human figure. Whereas the other Impressionists preferred to work outdoors capturing what they were observing at the moment, Degas preferred to work in his studio, sometimes working from photographs or from memory. What connects Degas to the others, however, is an interest in depicting modern life, an interest in light and an interest in using color in unconventional ways. Because there were profound differences in the individual Impressionist's artistic philosophies and because the group included some difficult personalities (including Degas) the group eventually separated. There were only eight Impressionist exhibitions and after 1886, the artists went their separate ways. Degas, who was having problems with his eye-sight, became particularly solitary. Increasingly, he turned to pastels and sculpture. Again and again, he returned to certain subjects such as dancers, horse racing and women bathing. He died in 1917. Sir William Burrell (1861 - 1958) amassed 20 major works by Degas including works from every period of the artist's life. He donated these along with some 9,000 other works of art to the City of Glasgow in 1944. The closing of the Burrell Collection Gallery in Glasgow for renovation provided an opportunity for the Degas to be exhibited in London. The exhibition was presented in three sections: Modern Life; Dancers and Private Worlds - - in short three of Degas' signature subject matters. Although there were a few oil paintings and drawings, most of the works in the exhibition were pastels, Degas' favorite medium The presentation of these works together served to underscore how much of an innovator Degas was. His use of this medium was much different than conventional pastels. The strokes are vigorous conveying energy. The shapes verge on the abstract at times. The colors are often strong and bold. “Eighteenth Century Pastel Portraits” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a small exhibit of European pastels. It includes, French, Italian, German and British works from the museum's collection.

An exhibition of pastels is not all that common. Works done in pastel are light sensitive. Prolonged exposure to light causes some pigments to fade. In addition, most pastels are done on paper and paper can fade or deteriorate with prolonged exposure to light. As a result, museums generally exhibit pastels in rooms with dim light and even then only for brief periods. The difficulties associated with such arrangements prevent museums from mounting pastel exhibitions very often. Essentially, a pastel is made up of pigment and a binder such as gum. The combination is then molded into a rounded or squared stick. The artist can then use the sticks in the same manner as a pencil. In other words, he or she can create a work without using brushes or mediums such as oils. Historically, pastels were often referred to as crayons. However, pastels differ from modern crayons in that the binder in crayons is usually wax. Pastels are more powdery than modern crayons. While crayons stick to paper better than pastels, pastels are easier to blend and they cover the ground more easily than crayons. Another somewhat confusing term that you often see is “pastel painting.” A pastel painting merely means that the pastels cover the entire ground. A pastel that leaves part of the paper exposed is a “pastel sketch.” It is believed that pastels were invented in the 15th century. There is evidence that Leonardo Da Vinci knew of pastels from a French artist in 1499. In any event, pastel portraits became very popular in Europe during the 18th century. People were attracted by the luminosity of the pastels and the speed and ease with which they could be used. The exhibit presents works by several of the leading pastelists of that era. Rosalba Carriera specalized in pastel portraits and became one of the most successful women artists of all time. She began by painting miniatures but by 1703, she had mastered pastels. Not long after, merchants, nobles and visitors to Venice were queuing for her pastel portraits. She went to Paris and painted the king and his nobles. She went to Vienna and the Holy Roman Emperor became her patron. Carriera is represented by a portrait of a young Irishman dressed in a cloak and tricorne hat. The mask that he has shifted away from his face shows that he is in Venice for the Carnival. Proud and dashing, it is the image of a young noble living life to the full in that romantic city. John Russell was the leading English pastel portraitist. In fact, he was appointed pastel artists to King George III. He also wrote the still inflential book Elements of Painting with Crayons. Russell is represented by three works. One is a charming portrait of his daughter with a baby. The other two are commission portraits of a merchant and his wife. She looks like the dominate one of the couple while he seems to have the look of someone who knows when he is well off. The signs by the paintings tell us that she was an heiress and that when the couple married, he took her family name. Adelaide Labille-Guiard was a member of the French royal academy of painting and sculpture. She is represented by a portrait of Elisabeth de France, the younger sister of King Louis XVI. A virtuous and religious person, there have been calls for pleasant looking person's beatification. However, there is always an element of tragedy in pictures of the members of this doomed family. The images in this exhibit are in sharp contrast to the familiar pastels of artists such as Degas. Rather than strong expressive lines, these works are soft and smooth with no trace of the artists' strokes. Still, they subtlety convey the personalities of the sitters. |

AuthorRich Wagner is a writer, photographer and artist. Archives

November 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed